- 592 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Routledge Handbook of Linguistics

About this book

The Routledge Handbook of Linguistics offers a comprehensive introduction and reference point to the discipline of linguistics. This wide-ranging survey of the field brings together a range of perspectives, covering all the key areas of linguistics and drawing on interdisciplinary research in subjects such as anthropology, psychology and sociology.

The 36 chapters, written by specialists from around the world, provide:

- an overview of each topic;

- an introduction to current hypotheses and issues;

- future trajectories;

- suggestions for further reading.

With extensive coverage of both theoretical and applied linguistic topics, The Routledge Handbook of Linguistics is an indispensable resource for students and researchers working in this area.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Routledge Handbook of Linguistics by Keith Allan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

What is linguistics?

1.1 Linguistics studies language and languages

Linguistics is the study of the human ability to produce and interpret language in speaking, writing and signing (for the deaf). All languages and all varieties of every language constitute potential data for linguistic research, as do the relationships between them and the relations and structures of their components. A linguist is someone who studies and describes the structure and composition of language and/or languages in a methodical and rigorous manner.

1.1.1 Human language

Linguistics inquires into the properties of the human body and mind which enable us to produce and interpret language (see Chapter 19). Human infants unquestionably have an innate ability to learn language as a means of social interaction (see Chapters 2, 13, 14, 17 and 20). Most likely it is the motivation to communicate with other members of the species that explains the development of language in hominins. It follows that linguists study language as an expression of and vehicle for social interaction. They also research the origins of human language (see Chapter 2), though there is controversy over when language first became possible among hominins. Neanderthals (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, c.300,000 to 30,000 years BP) almost certainly came to have the mental and physical capacity to use language naturally. No extant non-human animal has a communication system on a par with human language. Some creatures learn to respond to and even reproduce fragments of human language, but they never achieve what a human being is capable of. The so-called ‘language’ used within some animal communities may have a few identifiable meaningful forms and structures, but animal languages lack the depth and comprehensiveness of human language.

Human language is the most sophisticated means of communication among earthly life forms. It is a kind of interaction with our environment; and it is intentionally communicative. Inorganic matter interacts with its environment without intention, e.g. moving water reshapes land. Plants interact with their environment as individuals, e.g. many plants turn towards a light source and some insectivorous plants actively trap their prey, but this interaction does not result from intention. Non-human creatures often do intentionally communicate with each other, for instance when mating or seeking food, but only in very limited ways. Humans interact with their environment in many ways, of which human communication using language is the most sophisticated and results from intentional behaviour.

1.1.2 Some general characteristics of language(s)

Language has physical forms to be studied. You can hear speech, see writing and signing, and feel Braille. The forms can be decomposed into structured components: sentences, phrases, words, letters, sounds. These language constituents are expressed and combined in conventional ways that are largely (if not completely) rule-governed.

Chapter 3 examines gesture and sign as used in place of and along with spoken language. Gestures of various kinds accompany most spoken language (even when the speaker is on the telephone). Sign languages of the deaf vary from nation to nation, though each national sign language is also a complete language largely independent of the language spoken in the signer’s community.

Speech precedes writing both phylogenetically and ontogenetically. The creation of a writing system around 5,000 years BP (see Chapter 4) is the earliest evidence we have of linguistic analysis: all writing systems require the creator to analyse spoken language into chunks that correspond to words, syllables, phonemes or other phonic data in order to render them in a visual medium. Although writing systems usually begin with a pictographic representation, this very quickly becomes abstract as representations of sounds, syllables, and/or elements of meaning come to replace pictographs. Thus did writing become more symbolic than iconic.

Chapter 5 discusses the phonetic inventory of sounds that can occur in human languages and reviews the character of human speech mechanisms. Phoneticians research the physical production, acoustic properties, and the auditory perception of the sounds of speech.

Less than a quarter of the sounds humans have the ability to make are systematically used within any one language and Chapter 6 focuses on properties of the various phonological systems to be found in the world’s languages. Phonologists study the way that sounds function within a given language and across languages to give form to spoken language. For instance the English colloquialism pa ‘father’ in most dialects is pronounced with initial aspiration as [phaa] but in a few dialects without aspiration as [paa], which does not change the meaning.1 In Thai, however, the word [phaa] means ‘split’ whereas the word [paa] means ‘forest’, so the difference between [ph] and [p] makes a meaningful difference in Thai, but not in English. This is just one instance of different phonological systems at work and there is, of course, much more.

Morphology (see Chapter 7) deals with the systematic correspondence between the phonological form and meaning in subword constructions called ‘morphemes’. A morpheme is the smallest unit of grammatical analysis with semantic specification. A word may consist of one or more morphemes: for example, the morpheme –able may be suffixed to the verb root desire to create the adjective desirable. This adjective may take a negative prefix un– to form undesirable which can, in turn, be converted into the noun undesirable by a process sometimes called ‘zero-derivation’ because there is no overt marker of the nominalization. This noun may then be inflected with the abstract morpheme PLURAL which in this instance has the form of the suffix –s yielding the plural noun undesirables. Morphology deals with the creation of new word forms through inflections that add a secondary grammatical category to an existing lexical item (word) but do not create a new one. As we have seen, morphology is also concerned with the creation of new lexical items by derivational processes such as affixation, compounding (chairwoman), truncation (math(s) from mathematics), and stress change (perVERT [verb] vs PERvert [noun] – where upper case indicates the stressed syllable).

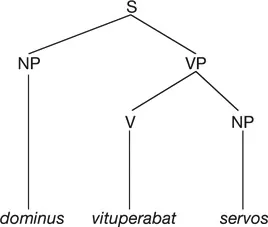

Syntax studies the manner in which morphemes and lexical items combine into larger taxonomic structures such as phrases, sentences and longer texts (see Chapters 8 and 9). Some languages incorporate many morphemes into a single word that requires a sentence to translate it into English. Relationships between sentence constituents can be signalled (1) by inflection, in which case word order can be comparatively free (as in Latin), or (2) by the sequence of items – making word order relatively rigid (as in English). Latin dominus servos vituperabat, vituperabat dominus servos, servos dominus vituperabat are all translated by the English sentence the master [dominus] cursed [vituperabat] the slaves [servos]. Although there are many ways of depicting syntactic structure, rooted labelled trees have become the norm in modern linguistics, e.g. the oversimplified tree in Figure 1.1. Chapter 9 argues that syntax should reflect the dynamics of language processing allowing for structural underspecification and update such that the patterns of dialogue can be shown to follow directly from the integrated account of context-dependent phenomena.

Language is metaphysical in that it has content; i.e. language expressions have meaning. Semantics investigates the meanings of sentences and their constituents and, also, the meaning relationships among language expressions. Linguistic semantics is informed by insights from philosophy, psychology, sociology and computer science. Notions of truth and compositionality are crucial in determining meaning (see Chapters 33 and 9). But so too are the cognitive processes of language users (see Chapters 29 and 35). There is a question of how lexical content corresponds with conceptual content and the structure of concepts. There is controversy over the place within lexical and discourse semantics of encyclopaedic knowledge about referents (things spoken of) and the domain within which a language expression occurs. There is also controversy about the optimal means of representing meaning in theoretical semantics. All these matters are reviewed in Chapters 10 and 11.

Figure 1.1 An oversimplified tree structure [S = sentence, NP = noun phrase, VP = verb phrase, V = verb]

Every language comes with a lexicon – loosely equivalent to the vocabulary of that language. A lexicon (see Chapter 12) can be thought of as the mental counterpart to (and original model for) a dictionary such as the Oxford English Dictionary. Lexical items are stored as combinations of form and meaning, together with morphological and syntactic (morphosyntactic) information about the grammatical properties of the item and links to encyclopaedic information about the item – such as its history and information about things it may be used to refer to. Typically, a lexical item cannot be further analysed into meaningful chunks whose combination permits its meaning to be computed. For instance, the lexical items a, the, dog, sheep, kill and morphemes like –s (PLURAL), –ed (PAST) can combine together under certain conditions, but none of these is subject to morphosyntactic analysis into smaller constituents.

The lexicon of a language bundles meaning with form in versatile chunks that speakers combine into phrases, sentences, and longer texts whose meanings are computable from their constituents. The lexical items and morphemes listed above can combine into the sentence in (1), the meaning of which is composed from not only the words and morphemes but also the syntactic relations between them.

(1) The dogs killed a sheep.

(1) has much the same meaning as (2) and a very different meaning from (3).

(2) A sheep was killed by the dogs.

(3) A sheep killed the dogs.

In (1) and (2) the dogs do the killing and the sheep ends up dead, whereas in (3) the sheep does the killing and it is the dogs which end up dead. Notice that the meanings of dogs and killed can be computed from their component morphemes: DOG+PLURAL and KILL+PAST; similarly for the phrases the dogs and a sheep and the whole of the sentences (1), (2) and (3).

If you find (1) and (2) more believable than (3), that is because you are applying your knowledge of the world to what is said. These judgements arise from pragmatic assessments of the semantics of (1), (2) and (3).

As said earlier, semantics is concerned with the meanings of, and the meaning relationships among, language expressions. For example, there is a semantic relationship between kill and die such that (4) is true.

(4) If X kills Y, then Y dies.

In (4) X has the role of actor and Y the undergoer. There are many other kinds of relationship, too. In order to die, Y has to have been living. If Y is a sheep, then Y is also an animal. In English, dogs and sheep are countable objects, i.e. they can be spoken of as singulars, like a sheep in (1)–(3), or as plural entities like the dogs in (1)–(3). Words referring to meat (such as mutton, lamb, pork) do not normally occur in countable noun phrases; the same is true of liquids like beer and granulated substances like sugar, coffee or rice. However, these nouns are used countably on some occasions to identify individual amounts or varieties, as in (5)–(7).

(5) Two sugars for me. [Two spoons of sugar]

(6) Three beers, please. [Three glasses or cans of beer]

(7) Two coffees are widely marketed in Europe. [Two species or varieties of coffee]

What this shows is that the grammatical properties of linguistic items can be, and regularly are, exploited to generate communicatively useful meaning differences.

When speakers employ language they add additional aspects of meaning. Although this is not obvious from (1), it is observable from the interchange between X and Y in (8).

(8) X: I don’t understand why you are so upset.

Y: The dogs killed a sheep.

Pragmatics (see Chapters 13 and 14) studies the meanings of utterances (an utterance is a sentence or sentence fragment used by a particular speaker on some particular occasion) with attention to the context in which the utterances are made. In (8) the reference of ‘I’ and ‘you’ is determined from context, as is the relevant time at which the addressee is judged upset and also the estimated degree of relevance of Y’s response to X’s statement. Language interchange is one form of social interactive behaviour and it is governed by sets of conventions that encourage cooperativeness in order that social relations be as harmonious as possible. There are competing notions of what constitutes cooperativeness, whether it exists independently of particular interlocutors or whether it is negotiated anew in every encounter, but, nonetheless, cooperative behaviour seems to be the default against which uncooperative behaviour such as insult and offensive language must be judged (see Chapter 14). What this amounts to is that interlocutors are socialized into having certain expectations of and from each other. These expectations are learned in childhood as one aspect of competent language usage; they are part of one’s induction into being a member of a social group. Typically they constitute a part of common ground between interlocutors that enables them to understand one another. Looking again at (8) we observe that Y’s response to X’s question is apparently relevant, because we know that many people get upset when dogs kill a sheep. Y has assumed this knowledge is part of the common ground with X, enabling X to take Y’s response as an appropriate one. This appropriateness is independent of whether or not Y is speaking truly. The default assumption for almost all language interchange is that speakers will be honest, which is the reason why lying is castigated in Anglo communities (and many others).

We see from (8) that spoken discourses have structures and constraints that render them coherent so as to be lucid and comprehensible to others. Were that not the case, the discourse in (9) between a therapist and a schizophrenic patient would not seem abnormal.

(9) THERAPIST: A stitch in time saves nine. What does that ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Contributors

- 1 What is linguistics?

- 2 Evolutionary linguistics: how Language and languages got to be the way they are

- 3 Gesture and sign: utterance uses of visible bodily action

- 4 Writing systems: methods for recording language

- 5 Phonetics: the sounds humans make when speaking

- 6 Phonology

- 7 Morphology: the structure of words

- 8 Syntax: putting words together

- 9 Syntax as the dynamics of language understanding

- 10 Semantics: the meaning of words and sentences

- 11 Lexical semantics today

- 12 Lexicography: the construction of dictionaries and thesauruses

- 13 Pragmatics: language use in context

- 14 The linguistics of politeness and social relations

- 15 Narrative and narrative structure

- 16 Anthropological linguistics and field linguistics

- 17 Sociolinguistics: language in social environments

- 18 Psycholinguistics: language and cognition

- 19 Neurolinguistics: mind, brain, and language

- 20 First language acquisition

- 21 Second language acquisition and applied linguistics

- 22 Historical linguistics and relationships among languages

- 23 Linguistic change in grammar

- 24 Language endangerment

- 25 Linguistic typology and language universals

- 26 Translating between languages

- 27 Structural linguistics

- 28 Biolinguistics

- 29 Cognitive linguistics

- 30 Functional linguistics

- 31 Computational linguistics

- 32 Corpus linguistics

- 33 Linguistics and philosophy

- 34 Linguistics and the law

- 35 Linguistics and politics

- 36 Linguistics and social media

- Index