eBook - ePub

The Nanjing Massacre: A Japanese Journalist Confronts Japan's National Shame

A Japanese Journalist Confronts Japan's National Shame

- 332 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Nanjing Massacre: A Japanese Journalist Confronts Japan's National Shame

A Japanese Journalist Confronts Japan's National Shame

About this book

This book is based on four visits to China between 1971 and 1989 by Honda Katsuichi, an investigative journalist for Asahi Shimbun. His aim is to show in pitiless detail the horrors of the Japanese Army's seizure and capture of Nanjing in December 1937. Unvarnished accounts of the testimony - Chinese victims and Japanese perpetrators - to the rape and slaughter are juxtaposed with public relations announcements of the Japanese Army as printed in various Japanese newspapers of the time. The bland announcements of triumphant victories stand in bitter contrast to the atrocities that actually took place on the scene. The story unfolds with horrible detail as we watch the triumphant progress of the Japanese army whose troops were bent on rape and killing in the so-called "heat of battle." Yet by recalling the testimony of Japanese soldiers and reporters who were on the scene, as well as reproducing dispatches by Japanese Army authorities at the time, Honda makes it clear that the atrocities were part of a studied effort directed by the Japanese high command to impress the Chinese people with the power of its army and the folly of resistance to it - the estimate of 300,000 killed in these "military operations" is no exaggeratoin. Honda has worked with other Japanese journalists and scholars who have attempted to reveal the truth of the Nanjing massacre, provoked by the efforts of right-wing Japanese, including, sadly, many government officials, to whitewash the whole incident, even to the point of contending that a "massacre" never happened. This gripping account of the atrocities and cover-up joins other exposes - Chinese and now German - in keeping alive the memory of this shameful event.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Nanjing Massacre: A Japanese Journalist Confronts Japan's National Shame by Katsuichi Honda,Frank Gibney,Karen Sandness in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

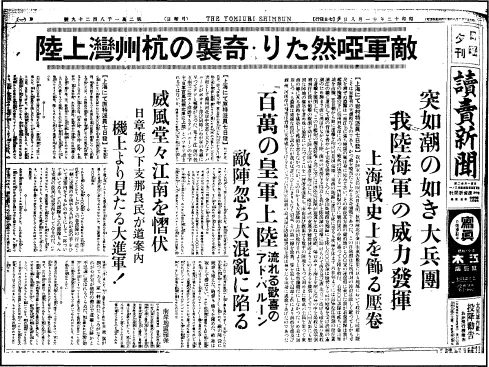

“ONE MILLION JAPANESE TROOPS LAND NORTH OF HANGZHOU BAY”

The evening edition of Yomiuri Shimbun, giving further reports of the landing at Hangzhou Bay. An article about the balloons advertising the “million person landing” can also be seen.

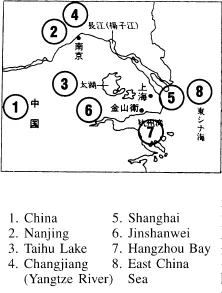

Before dawn on November 5, 1937, Japan’s 10th Army, made up of the 6th (Kumamoto) Division, the 18th (Kurume) Division, and the 114th (Utsunomiya) Division, landed under opposing fire on one arm of Hangzhou Bay near Jinshanwei. A secret operation carried out under the escort of approximately 100 ships of the Japanese Navy’s Fourth Fleet, it was the beginning of a large-scale invasion that would culminate more than thirty days later in the fall of Nanjing, then China’s capital.

The five divisions of the Shanghai Expeditionary Force (the 3d Division from Nagoya, the 11th Division from Zentsūji, the 9th Division from Kanazawa, the 13th Division from Sendai, and the 101st Division from Tokyo), which had been facing strong resistance from the Nationalist Chinese Army of Chiang Kai-shek, shifted their efforts to moving toward Nanjing, chasing the retreating Nationalist forces ahead of them. Later, they were joined by the 16th Division from Kyoto. The China Theater Headquarters was established under the command of General Matsui Iwane in order to direct the 10th Army and the Shanghai Expeditionary Force.

The evening edition of the Tōkyō Nichinichi Shimbun (predecessor of the Mainichi Shimbun), announcing the landing at Hangzhou Bay.

The Asahi Shimbun covered the landing at Hangzhou Bay as follows:

[Official announcement from the War Office, noon, November 6] Part of our army, with close and appropriate cooperation from our navy, executed a difficult landing under enemy fire on the north side of Hangzhou Bay before dawn on the 5th. The landing was a great success.[Official announcement from the Navy Department, noon, November 6] At the behest of the Commander-in-Chief of the China Fleet, part of our forces under the direction of the Commander-in-Chief of the -th [sic] Fleet, escorted the troop transport ships under utmost secrecy and entered Hangzhou Bay before first light on the 5th. Riding on rough seas and fighting the thick fog that assailed them, they did their utmost to cover the military party’s landing, successfully achieving the expected objectives.[Special telegram from Shanghai, November 6] Announcement from the Military Information Office, noon, November 6: Before dawn on the 5th, a fairly large military party under close and appropriate cooperation from the navy, made a decisive landing under enemy fire in a district on the north side of Hangzhou Bay, successfully surprising and crushing the enemy in the vicinity. They are currently making great military gains.(Evening edition of November 7, 1937; published on the 6th1)

Although the Japan-China War had actually begun with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident (called the 7/7 Incident in China) on July 7, 1937, and continued with the second Shanghai Incident, the offensive against Nanjing was a turning point. With these victories, the Japanese military lost its ability to turn back and eventually found itself caught up in a quagmire. Even if we take the long view, following Japan’s trail through China for half a century from the Sino-Japanese War through World War II and then to defeat, the Nanjing offensive was a major milestone.

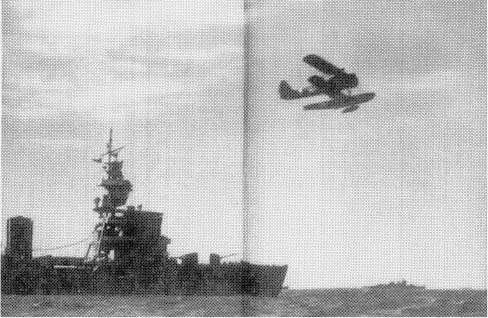

From a special extra issue of Asahi Graph: “Our fleet presses on splendidly toward Hangzhou Bay.”

It is widely known that after the landing at Hangzhou Bay, balloons were launched in Shanghai and elsewhere proclaiming, “One million Japanese troops land north of Hangzhou.” There may well have been one million troops, but the balloons were largely a strategy designed to crush the morale of the Nationalist troops offering resistance in the vicinity Here is a dispatch from a special correspondent in Shanghai, which appeared in the evening edition of the Yomiuri Shimbun on November 8, 1937:

At noon on the 6th, a large advertising balloon unfolded and floated high in the skies over the north bank of the Suzhou River, and at the same time a great war cry suddenly arose from our troops. Look! Can you not clearly read what is written on the balloon floating lazily in the low rain clouds south of the Yangtze River? “One million Japanese troops land north of Hangzhou Bay.”

The Nanjing offensive was a massive event, both in its scale and in its historical significance, so quite a few newspaper reporters and novelists followed the troops. In addition to their records, announcements, and reports, a number of memoirs from the officers and enlisted men themselves remain. Even though they operated under the limits of both military censorship and self-censorship, the works of such writers as Ishikawa Tatsuzō and Hino Ashihei also contain things that deserve reexamination. Hino participated in the Hangzhou Bay landing as a noncommissioned officer, and he published an account of his experiences under the title of Earth and Soldiers.

Either of Hino’s heartfelt memoirs, Earth and Soldiers or Barley and Soldiers, probably could have been used as an antiwar tract, but the author did not intend them that way. Rather, they are filled from beginning to end with deep affection for the fellow soldiers who suffered with him. In it, for example, he describes what happened when his unit captured a pillbox. (Excerpted from the edition published by Shinchō Bunko.)

The Chinese soldiers piled out of the pillbox. All of them looked very much like Japanese people. They seemed to have been hit by a hand grenade, and they appeared one after another: one gasping for breath, one with his face scorched black, one with his chin blown away, one with his left cheek in shreds. They bowed obsequiously, their hands together, with expressions that seemed to plea for help. … We thought there weren’t any more of them, but then I heard voices moaning loudly in the darkness. Straining my eyes, I saw some dark people squirming on the dirt floor of the middle room. I moved closer, my pistol at hand. … However, they weren’t moaning; they were crying. I got down on the floor and touched those two soldiers who were making such a pitiful noise. “Lai, lai,” I said. “Come, come.” They finally stood up. The faces that came into view out of the darkness by the light that seeped in through the gunsight were so young and beautiful that I was startled. Both of them were about the same age, almost boys, and so beautiful that they could have been mistaken for girls. Their faces were streaked with tears, and they leaned on my shoulders. They began to say something, but of course, I didn’t understand them. One of them took a notebook out of his pocket and showed me a photograph, which I assumed was a picture of his mother. I could easily imagine what they were saying, and I thought they must be brothers. I briefly considered leaving the two of them behind when we withdrew. However, with the two of them leaning on either shoulder, I led them out front. They urgently put their hands to their necks, as if begging me not to kill them. I nodded my agreement. I thought a saw a touch of joy pass across the dejected faces of these young soldiers. … When I returned to the village where the main battalion was already camped, there were prisoners lined up in a row. Private Yoshida came up to me. “Sir,” he said, “chow is ready.” I went into the house, and then to a creek out back to wash my face and hands. I seemed to have injured one ear a bit. My first rice in a long time tasted wonderful, as you can imagine.

From a special extra edition of Asahi Graph reporting on the Japanese military landing at Hangzhou Bay. This is the landing of the rear guard units following the landing of the advance units on November 5.

Yet, when this work was published, the following lines were deleted by the censor, although, of course, they have been restored in the currently published version. They describe the massacre of the prisoners:

I became drowsy as soon as I lay down, and I slept for a while. I woke up on account of the cold and stepped outside. There was no sign of the prisoners who had previously been tied together with electrical wire. When I asked a nearby soldier what had happened to them, he said, “We killed them all.”I saw that the bodies of the Chinese soldiers had been thrown into a trench. The trench was narrow, so they lay on top of one another, some of them half submerged in muddy water. Had they really killed thirty-six people? I was at once sad, furious, and nauseated. I was about to turn away in my dejection when I noticed something strange: the bodies were moving. I looked closely and saw a blood-streaked, half-dead Chinese soldier moving around among the bottom layer of corpses. Perhaps he had heard my footsteps; in any case, he laboriously pulled himself up with every bit of strength and looked straight at me. His agonized expression horrified me. With a pleading look, he pointed first at me and then at his own chest. There wasn’t the least doubt in my mind that he wanted me to kill him, so I didn’t hesitate. I set my sight on the dying Chinese soldier and pulled the trigger. He stopped moving. Platoon leader Yamazaki came running. “Why did you waste a shot like that when we’re surrounded by the enemy?” he said. I wanted to ask, “Why did you do such a horrible thing?” but I couldn’t say it. I left with a heavy heart.

That the above account is fact, not fiction, was substantiated by the literary critic Kobayashi Hideo, who was in China as a special correspondent for the magazine Bungei Shunjū and wrote about the incident as follows, after hearing of it directly from Hino. The “x’s” in the text are evidently parts deleted by the censors.

This is what happened. Hino led seven soldiers who, using the dead angle of the machine gun to approach the largest pillbox, scrambled up, and tossed seven hand grenades through the ventilation pipes. Then they went around to the back, broke down the doors, and jumped in. They cut down four men and tied up thirty-two regular troops with xxx. Hino said, “I just couldn’t kill those guys once we had them tied up, but with the situation being what it was, well, I didn’t know about it, but when I went out at night, there were xxxxxxxx in the trench. Among them there was a guy pointing to his chest and begging me to kill him, and I felt sorry for him, so I xxxxxx him.

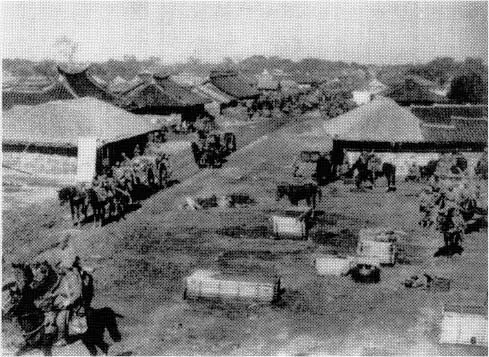

From a special extra edition of Asahi Graph reporting on the landing at Hangzhou Bay. The caption of this photograph reads, ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Editor's Introduction

- Translator's Note

- Author's Preface to the U.S. Edition

- 1. “One Million Japanese Troops Land North of Hangzhou Bay”

- 2. “More of Our Troops Land at Shanghai”

- 3. “The City of Suzhou Has Finally Fallen”

- 4. “The Imperial Army Occupies Wuxi”

- 5. “The Rising Sun Flag Over the City Walls of Changzhou”

- 6. “Seizing Jurong, We Charge Onward”

- 7. “Zhenjiang Occupied”

- 8. “The Contest to Cut Down a Hundred Goes Over the Top”

- 9. “The Imperial Forces Make an All-Out Charge on Nanjing”

- 10. “A War of Annihilation Unfolds”

- 11. “Nanjing, Where Peace Has Been Restored”

- Afterword to the Original Edition

- Afterword to the Original Paperback Edition

- Commentary

- Appendix

- Index