![]()

PART 1

Other voices

Indigenous peoples

We are not a materialistic people; we live by muscle, mind and spirit.

Eric Anoee, Inuk Elder, Arviat, Northwest Territories, Canada (Heath 1997: 156)

![]()

INTRODUCTION

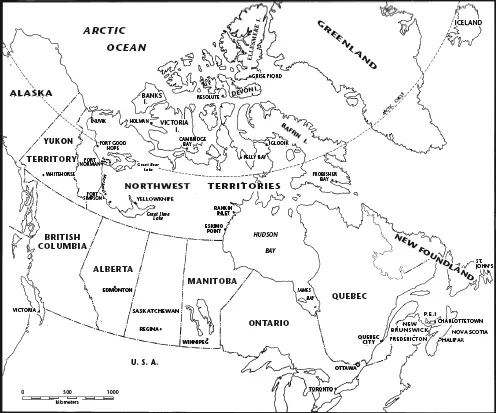

I encountered the “other voices” immediately upon arriving in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada (NWT) in 1976, as a museum director with no prior experience and fresh from graduate school. These voices came not only from the diverse peoples of the NWT, but also from the land itself. It was then that I sensed for the first time the meaning of social ecology – that social and environmental issues are intertwined and both must be considered simultaneously (Barnhill 2010: 91). The intertwining of society and the environment is no more pronounced than it is in the Northwest Territories of Canada, an immense wilderness region with a population that was two-thirds Native born – Inuit, Dene or Metis. Dualistic thinking is a liability here, in the home of the world’s greatest hunting cultures.

This cultural diversity, coupled with the severe climate and isolation, posed a number of surprising challenges to me as a newly minted custodian of mainstream museum traditions. Reality immediately intervened with a barrage of complexities. How do you address the stated perception among northern Aboriginal peoples that museums are a colonial legacy and do not address the needs of living cultures? How do you involve Aboriginal peoples in the development of a museum in their homeland, at a time when their political aspirations were demanding acknowledgement and redress? Are environmentally controlled museums in remote Subarctic and Arctic communities necessary, achievable, or preposterous? What is the best organizational design to unleash individual talent and commitment? Should a museum have a single focus or be multidisciplinary? The questions multiplied daily, intensified by the absence of any museum precedents or experimentation in this remote region that could show the way. It was both disconcerting and motivating, and it demanded study, reflection, and action. In retrospect, it was a rare opportunity to move beyond the shadow of orthodoxy, think anew, and develop alternatives.

The obvious remedy was to rely on the received wisdom of traditional practice, but I was a novice and not yet immersed in the constraints of professionalism. My tenure as the founding director of the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre (PWNHC) was one of merging professional standards with the realities of time and place – while always hoping to achieve a standard of excellence and quality in the work at hand. Living beyond the establishment aura allowed our staff and me the naiveté and freedom to learn, experiment, make mistakes, and grow.

The heart of the museum, the collection, is a case in point. Many of the 65 NWT communities wanted a museum to preserve and highlight their cultural traditions, but not in a manner that conformed to professional museum practice – that is, not in a permanent collection in an environmentally controlled building. The preservation and celebration of intangible cultural heritage – music, dance, and storytelling – were often the focus of concern, not the preservation of objects. Mainstream museum practice dictated, however, that a professional, publicly funded museum had to have environmental controls because without them the collections would deteriorate.

It was both my duty and my belief to convey this tenet to northern communities, and this I did until I began to listen more deeply. It soon became clear that the majority of people in the NWT’s remote communities were not interested in adhering to professional museum practice; not out of any disrespect or hostility, but primarily because of their particular world-view in combination with the consequences of geographic isolation. As a result of listening and learning together, we developed alternative approaches to museum work, while also respecting museum traditions and professionalism. I cannot over-emphasize the inclusivity I experienced in the NWT, especially among the Dene, the Inuit, and the Metis. This was the nature of their societies – open, sharing, and respectful. I absorbed this inclusivity and brought it to the conduct of our work, as did my colleagues.

My directorship at the PWNHC was also an inadvertent exercise in social justice – another observation that has only become apparent to me in retrospect. At that time, the NWT was unable, legally or practically, to keep its cultural property in the territory. All material culture, including archaeological remains and archival documents, was sent to Canada’s national museums in Ottawa, Ontario.1 Rarely, if ever, were any of the objects shared or returned to the NWT. Northerners were decidedly unhappy with this arrangement and sought to keep their material heritage in their homeland.

The first strategy in undoing this colonial legacy was the development of a fully professional museum, a project that had the support of the NWT’s political leaders and citizens. In retrospect, this was akin to a large-scale repatriation effort and was made possible by some of those same professional standards, such as environmentally controlled buildings, that I also criticize in the chapters that follow. This was my initial foray into the paradoxical world of museums.

The first two chapters below represent 10 years of individual and collective effort to make sense of the many questions noted above, as we worked to develop museum services in one-third of Canada’s landmass. The chapter on “Northern Museum Development: A View from the North” lays out the challenges of museum development in a remote region, with an inquiry into alternative approaches to heritage preservation with the involvement of Indigenous peoples. The second chapter, “Museum Ideology and Practice in Canada’s Third World,” is a retrospective assessment of our work at the PWNHC, including an analysis of the ideas, values, and beliefs that guided our work. These considerations are rarely made explicit in the museum literature and I hope that a discussion of ideology helps to clarify the politics of culture that are still unfolding throughout the world. There are many lessons to be learned here for application elsewhere, but I doubt that there has ever been a more open and creative environment for growing museums than in the NWT 40 years ago.

The experience of living and working in the NWT was uppermost in my mind when I became the Director of the Glenbow Museum in 1989. I was highly motivated by what I had learned in the North and energized by the possibilities of furthering this work at Glenbow – a large, multidisciplinary institution with an international reputation and significant resources. I was surprised and dismayed to see the marginalization of First Nations peoples in the province of Alberta (Canada), unlike the NWT, where Aboriginal peoples held positions of authority throughout society and constituted the majority in the NWT Legislative Assembly. The Glenbow Museum was in the homeland of the Blackfoot Confederacy, although the Blackfoot’s needs and aspirations were largely unheeded by the museum.2 This was more a result of benign neglect and disinterest than any intentional ill-will or conflict.

Thus began a decade-long process of discovery and learning, eventually culminating in the largest, unconditional repatriation of First Nations sacred objects in the history of Canadian museums, in 2000 (Janes 2015: 241–262).). Although this repatriation was a highly visible and public event, the chapters that follow describe the modest, incremental growth in our evolving relationship with the Blackfoot – a process of reciprocity, deepening understanding, and mutual appreciation. The chapter on “First Nations: Policy and Practice at the Glenbow Museum” chronicles our attempt to improve relationships with First Nations through the development of both policy and practice. In “Personal, Academic and Institutional Perspectives on Museums and First Nations,” I draw together what I had learned by 1994. These three perspectives are ultimately seamless, with each informing the other. Personal agency underlies these perspectives, as does risk taking. The last chapter in Part 1 is “Issues of Repatriation: A Canadian View,” wherein the late Gerald Conaty and I challenge the European opposition to the return of sacred objects to North American museums.

I was recently told that addressing historical injustices (including repatriation) among museums, First Nations, Inuit and Metis in Canada is actually about human rights. I have never thought of this work in that way – my motivation was born of respect for diversity, a predilection for activism, and the undeniable presence of moral considerations – all of which the reader will note in the following chapters. Whether or not it is a human rights issue is not as important as the need to continue to address these unresolved issues. The progress is decidedly uneven across Canada, as it is among those museums worldwide that hold Aboriginal collections.

In addition, the museum community must now contend with the “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums.”3 Signed by numerous luminaries of the museum world, the Declaration rejects repatriation on the grounds that “universal museums,” with their encyclopaedic collections, are best positioned to act on behalf of the world. Despite this arrogant and retrogressive manifesto, I am hopeful that the next generation of museum workers will ensure that museums and Aboriginal peoples continue to collaborate and flourish, in a manner that will confirm the human rights of all Indigenous peoples in museums. The chapters in Part 1 embody this ambition.

Notes

1 Because of its status as a territory, rather than a province, Canada’s Federal Government retained significant authority over territorial affairs. The devolution of political and administrative powers from the federal government to the NWT continues to unfold.

2 The Blackfoot Confederacy consists of four First Nations; the Kainai (or Blood), Siksika (Blackfoot; Northern Blackfoot), Apatohsipiikani (Piikuni, Peigan), and Ammskaapipiikani (Piegan, Blackfeet).

3 The full text of the “Declaration of the Importance and Value of Universal Museums” is contained in the International Council of Museums Thematic Files. See: http://icom.museum/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/ICOM_News/2004–1/ENG/p4_2004–1.pdf.

References

Barnhill, D. L. (2010) “Gary Snyder’s Ecosocial Buddhism.” In R. K. Payne (editor), How Much Is Enough? Buddhism, Consumerism, and the Human Environment. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications.

Heath, T. (1997) “Comments from Afar.” In R. R. Janes, Museums and the Paradox of Change: A Case Study in Urgent Adaptation. Calgary, Canada: Glenbow Museum and the University of Calgary Press.

Janes, R. R. (2015) “The Blackfoot Repatriation: A Personal Epilogue.” In G. T. Conaty (ed.) We Are Coming Home: Repatriation and the Restoration of Blackfoot Cultural Confidence. Edmonton, Canada: The Athabasca University Press, pp. 241–262.

![]()

1

NORTHERN MUSEUM DEVELOPMENT∗

A view from the North

Introduction

It is a recognized fact that Canadian museum development is centered in the southern tier of the country, where various common factors have contributed to the shaping of philosophical and pragmatic approaches to museums in Canada. These common factors include the numerical dominance of Euro-Canadians and their perceptions of museums, physical environments that fall within a certain range, and established communication and supply networks, to mention only a few.

When museums are extended into the Canadian North, however, they become part of a context that is qualitatively and quantitatively different than that of southern Canada, particularly with respect to environmental, societal, economic and political factors. These differences are so significant that those who are concerned with planning and implementing policies for museums and related activities in northern Canada must be prepared to meet the challenge of this new context. Others who are less directly involved in northern museum affairs should also be aware of potentially new dimensions in thinking about Canadian museums.

I would like to make some observations on northern museum development from my perspective as the Director of the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre (PWNHC) in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada. Our experiences in creating what was at first a rather traditional museum in a northern setting are useful in elucidating some of the unique features of the northern context referred to earlier. In addition, our adjustment to various northern realities, as well as some thoughts about future directions for northern museums, are discussed. Although my comments refer specifically to the Northwest Territories, I am hopeful that at least some of them are applicable to other northern regions of the country.

The land and the people

The Northwest Territories occupies a total area of 3,376,689 square kilometers of forest, lakes and tundra north of the 60th parallel, or one third of the landmass of Canada [in 1999 the Northwest Territories was divided to form the Nunavut Territory]. The climate is semi-arid and severe, with temperatures ranging from 35°C to −56°C. The population of this entire region is a mere 46,398, resulting in an astoundingly low population density.

Over two-thirds of the population is native born, and consists of Inuit, Dene, and Metis peoples.1 The remaining portion includes Euro-Canadians and those of other ethnic origins. At least eight different languages are spoken and residents live in and around 64 communities. Less than one quarter of these communities can be reached by road from southern Canada. The remainder depends upon aircraft and boat, as well as ice roads which are open in the winter only. As a result, transportation and communication problems are significant.

As a result of many factors, not the least of which is isolation, with its mental and physical costs, a significant portion of the Euro-Canadian population is transient. Many people come for one or two years and leave never to be seen again. In addition to the cynicism which these recurrent migrations provoke among the permanent residents, there are frustrating results for the operation of local museums. I have seen communities develop excellent boards with highly motivated staff, only to have these organizations dissolve after a brief period. The key to overcoming this is to foster the same degree of interest among the permanent residents, the majority of whom are Inuit, Dene or Metis. Only then will there be stability in community museum affairs.

The political setting

Unrecognized by many who work in the museum field, the concept o...