![]()

Part I

Introduction

The great unknowns

![]()

1 The great unknowns

Post-socialist economies and societies in motion

Human anatomy contains a key to the anatomy of the ape.

Karl Marx, The Grundrisse

Introductory remarks

This book is about a complex process of economic and social transformation in a relatively unknown, for Western development economists, region of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE or EE) and the former Soviet Union (FSU)—the former socialist economies.1 One of the principal arguments of this book is that affecting every country in the region, the process of transformational change launched in the late 1980s and early 1990s is still very much ongoing. As such, the transformation has and continues to affect every fiber and foundational tenet of the existent and emerging societies, cultures, economies, and politics.

Back when it all started, the transformation process was dubbed transition from a socialist system to a capitalist, or free market-based, economy. However, from the very start things did not go as, ironically, planned. A myriad of social and political economy nuances emerged, disproving any hypothetical economic models promising a smooth slide into a new equilibrium. Confirmation of these observations may be found in the vast and very diverse academic and policy literature that the present study attempts to unify in a structured discussion.

This book is an attempt to rationalize the complexity of this massive social change that involved almost complete eradication of the old and, in turn, nurturing of the new institutions. As a result, matured societies of the region learned from scratch how to walk and read in a qualitatively new environment. Undeniably, the early years of transition took a heavy toll in terms of industrial collapse, economic structure destruction, and sharp declines in living standards across the CEE/FSU region.

A peculiar fact is that the adjustment, a term used here with a great degree of approximation, to the new market-based system was quite different across each, by now politically, newly independent state. Unfortunately, these days, more than two decades since the reforms, the actual nuances remain virtually unknown to a broad research field, epitomized by the propensity to average out some country-specific tendencies and to often disregard unique nuances.

History holds the key to understanding some of the early transition era differences and what by now has evolved in place of the old system over two decades since the launch of free-market reforms. The heterogeneity of the political and economic entities simultaneously involved in the transition process defies any formal one-size-fits-all rationalization.

Nearly 400 million people live in what today is broadly known as the transition economies. As of early 2015, that is roughly 100 million more than the total population of the US and approximately 100 million less than the population of the European Union (EU). This is an immensely rich and diverse region in terms of culture, arts, languages, societies, history, politics, geography, climate, and, necessarily so, economics.

Moreover, dozens of different languages and hundreds of dialects are spoken across the vast expanse of what once superfluously seemed monolithic in its form. In Russia (the largest country in territorial and economic terms) there are over 190 ethnic groups with almost 40 spoken languages.2 And that is just based on broadly accepted historical trends. More recently, with the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 and human migration on a massive scale across the region, many more ethnicities and languages have emerged in the daily lives of average Poles, Russians, Kazakhs, Ukrainians, and all others.

We will deal with some of these questions, and migration in particular, a bit later. For now, let’s lay out the game plan for what follows. How should one study these transition economies? Should one just focus on the mechanics of economic policy in each country that we are about to discuss? Or is it more worthwhile to look at the nuanced and often very complex differences of the societies involved? Or, as a less-prose-interested pragmatic investor would suggest, how do these countries fit in the “emerging financial markets” portfolio strategy that seems to dominate the business media these days?

Perhaps the true answer to the above lies somewhere in the middle. In this book, we will try to address some of the related issues directly with references to accumulated statistical data. Certainly, such evidence offers our study a benefit of hindsight, a privilege not enjoyed by the commentators and economists who worked on the transition reforms in real time back in the early 1990s. Yet, an objective analysis is overdue.

In the process some readers are set to uncover a whole new world of alternative economic development models. Some will refresh their knowledge of the region. And hopefully, all, upon reading this book will gain a new, more impartial, appreciation for the complexity of the social and economic transformation that is still ongoing in these post-socialist nations. Let’s start with the basics: identifying the countries within the focus of this book.

Where are they on the map?

It helps when studying any particular geographical region to be able to identify it on the map. This is especially so when the analysis involves 29 newly independent nations. Figure 1.1 helps shed some light on this. Though, perhaps, not the most perfect graphical portrayal, this is the region we are studying.

Due to a range of political controversies, some of which may become relevant as we move along in our exploration, the actual borders shown in Figure 1.1 may at the time of reading be a bit more flexible than standardized maps might suggest. Clearly, the politics of independence movements, self-determination, and, the most tragic, regional wars, have and continue to affect regional administrative borders. Still, Figure 1.1, as an approximation, should be a good enough reference to start the conversation.

Geographically, the region covers all Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union countries. The region is vast, ranging from Germany’s eastern borders all the way to Russia’s border with Alaska; from the Arctic Ocean in the north to Afghanistan’s and China’s northern borders in the south.

Listing all the 29, Table 1.1 helps us sort these countries further by regional agglomeration, often come across either in the media or academic publications. In addition, references are made to the unrecognized, semi-independent nations that have emerged out of the socialist system breakup in the early 1990s.

Figure 1.1 Schematic map of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

Table 1.1 Transition economies by regional agglomeration | Region | Sub region | Country |

| Central and Eastern Europe | EU periphery | Albania; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Croatia; Czech Republic; FYR Macedonia; Hungary; Kosovo; Montenegro; Poland; Romania; Serbia; Slovak Republic; Slovenia |

| |

| | |

| | Baltics | Estonia; Latvia; Lithuania |

| | Caucasus | Armenia; Azerbaijan; Georgia |

| | Central Asia | Kazakhstan; Kyrgyz Republic (Kyrgyzstan); Tajikistan; Turkmenistan; Uzbekistan |

| Former Soviet Union | Eurasia | Belarus; Moldova; Russian Federation (Russia); Ukraine |

| | Unrecognized or partially recognized states | Abkhazia; South Osetia; Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh); Transnistria (Pridnestrovie) |

Table 1.2 Transition economies by economic or political association | Agreement | Country |

| Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) | Armenia (1992); Azerbaijan (1993); Belarus (1991); Kazakhstan (1991); Kyrgyz Rep (1992); Moldova (1994); Russia (1991); Tajikistan (1993); Uzbekistan (1992) |

| European Union (EU) | Czech Republic (2004); Estonia (2004); Latvia (2004); Lithuania (2004); Hungary (2004); Poland (2004); Slovakia (2004); Slovenia (2004); Bulgaria (2007); Romania (2007); Croatia (2013) |

| Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) | Armenia (2014); Belarus (2014); Kazakhstan (2014); Russia (2014) |

Note: Years of accession or agreement ratification are in parenthesis. For CIS Turkmenistan (1991) and Ukraine (1991) as associate states; Georgia (1993) withdrew in 2008.

It is also important to keep in mind that these days many of the CEE/FSU economies are either members or signatories to various regional or other multilateral association agreements. Among those, three—Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), European Union (EU), and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU)—stand out as the most important ones. According to this classification, the intra-regional divisions are intensified even further, as shown in Table 1.2.3

At first strike, Table 1.1 and Table 1.2 present a somewhat straightforward divergent course of broad, regional (involving parts of Europe proper and spreading into Asia) integration, or disintegration, depending on one’s preferences. However, perhaps, a more challenging way to analytically process this is to see a complex mix of adaptation and social evolution strategies in the region. The political and economic associations that the countries choose to join or to leave also reveal such social and political complexity.4

The map-view approach is instrumental to our analysis. Such an approach embodies the dialectics of the post-socialist transition: perceived unity across the space riddled with numberless divisions across terrain, national customs, and culture as well as across economic structures, social make-up and political preferences. Studying the map in Figure 1.1 for long enough and equipped with solid knowledge of the region’s history, a careful observer is then set to develop a responsible understanding of the economic and political choices the countries of the EE/FSU region have dealt with since the launch of the transformational reforms over two decades ago.

Many of those choices are dictated by historical leanings, political legacy, and more often, pragmatic economic reasons. The latter may describe the effect of the smaller, in economic terms, economies seeking integration with their major trading partners versus more economically independent, relatively larger economies seeking access to competitive markets. Be that as it may, even one’s basic knowledge of history should reveal the fact that we are dealing with a very diverse and unique region in economic, cultural, political, and historic contexts. History and memories of history and, more often, perceived memories of history, play a critical role. Those perceptions shape not just local traditions but also local economies, infrastructure, trade links, social norms, collective mentality, and national politics.

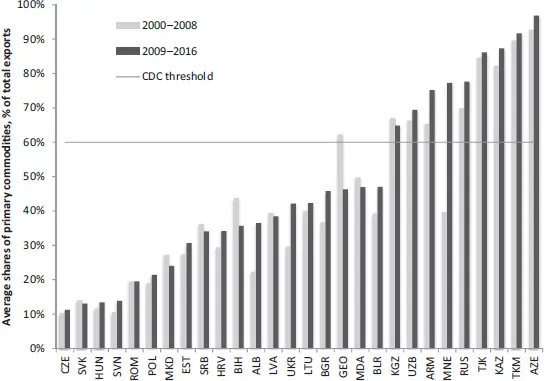

From an economic development aspect, the countries in our study may also be ranked based on their external performance. Figure 1.2 arranges the countries based on their average ratios of the values of commodity exports to the overall merchandise exports broken down into two periods (2000–2008 and 2009–2016, with 2009 as the crisis year). This is consistent with a commodity dependence analysis conducted recently by UNCTAD (2015), when a country is considered dependent on its primary commodity exports if the above ratio exceeds 60 percent threshold. Similar to analysis in Gevorkyan (2011), some can be characterized as commodity-dependent countries (CDC) or net commodity exporters (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and others). These rely primarily on energy and agricultural products exports. In another group, net commodity importers, commodity imports seem to dominate the exports.5

Figure 1.2 Primary commodity dependence in CEE and FSU, % of merchandise exports.

The time period chosen in Figure 1.2 coincides with the second decade of post-socialist development, which is often seen as the period of macroeconomic stabilization and relative emerging maturity in the EE/FSU. In other words, here we have information about a relatively transformed economic and industrial structure in each case. Certainly, in the present form this analysis is quite partial and trivial. Yet, to some extent, this analysis does help us draw a clear structural demarcation line. It would be important to keep this exports-based distinction in mind moving along in our journey, avoiding the common pitfall of lumping all transition economies together.

The CDC designation is significant in economic development terms. On the one hand, the CDC factor may be seen as the ultimate “resource curse” that invokes a host of associated problems of underdevelopment. On the other hand, despite the “resource curse,” in the post-socialist context, there may be an opportunity to leverage the CDC position to stimulate sustained and inclusive growth.6 Which of the two scenarios plays out in the post-socialist countries will really depend on the individual cou...