This book is available to read until 16th March, 2026

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 16 Mar |Learn more

Primate Ethnographies

About this book

Applies an ethnographic perspective to the study of primatesPrimate Ethnographies, 1/e is a collection of first-person accounts of immersive field studies of primates, people, and institutions, revealing the wide spectrum of primate science (primatology). Essays cover such primates as lemurs, New World monkeys, Old World monkeys, and apes. Readers experience the excitement of discovery and the challenges of primate field research. Primate Ethnographies can be used as a textbook or a companion reader.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Introduction

1

Primate Ethnographies

The Biological and Cultural Dimensions of Field Primatology

Like other researchers in the biological sciences, primatologists employ empirical methods to collect systematic data that permit quantitative analyses of behavioral, ecological, and evolutionary hypotheses. We are not ethnographers trained to study or write about human cultures. During the course of our primate field studies, however, we spend years, sometimes decades, living and working in close proximity to local people whose lives we also come to know. Perhaps this is why the ethnographer’s challenges of conducting fieldwork far from home, often in a secondary language acquired solely for that purpose, resonate so closely with my own experiences in a small rural community in southeastern Brazil over the past 30 years.

Although my research has focused on the northern muriqui (one of the most critically endangered primates in the world) rather than on humans, it has not taken place in a cross-cultural vacuum. Indeed, even the most reclusive primate field researchers become embedded in the socio-political, economic, and ideological contexts of the local human communities within and around which their research takes place. These human dimensions of primate fieldwork can be as diverse and as tricky to navigate as the tropical habitats in which most primates live. They can also influence the directions that our studies ultimately take, and thus impact what we learn about the primates. Yet in the scientific literature on primates, the cultural contexts of the field research and the effects of these interacting dynamics on both the primates and the primatologists are stories that seldom get told.

Primate Ethnographies is intended to span this gap between the biological and the social science sides of primate field research. The essays in this volume are written by established primatologists whose experiences, backgrounds, and motivating questions provide glimpses into the different pathways one can follow into the field of contemporary primatology. The contributors include biologists, psychologists, and physical anthropologists, whose interests range from the evolution of social behavior and communication, to feeding and community ecology, socioecology, and reproduction and life history theory. Their methodological approaches span the continuum from hands-off observational studies, to capture-and-release projects, to comparative investigations of captive and wild populations. The expertise of the contributors encompasses a broad taxonomic, geographic, and ecological diversity of primate species. Some of the contributors were among the first generation of primatologists to test explicit hypotheses about primate behavior in the field; some, like myself, have worked on the same populations of primates for decades. Still others have conducted comparative studies of different populations of a single species or of different species, requiring them to traverse continents, encountering new cultural conditions at each site.

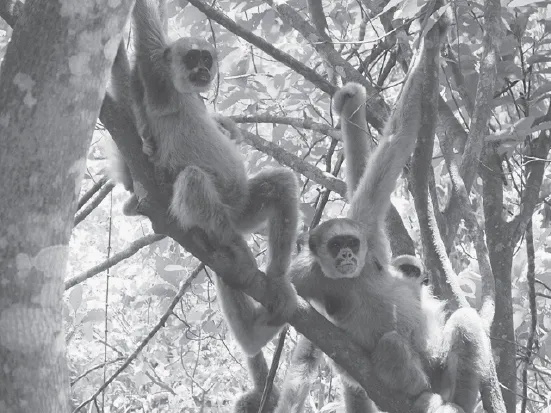

FIGURE 1.1 Northern muriqui females and their offspring at the RPPN Feliciano Miguel Abdala, in Caratinga, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Photo credit: Carla B. Possamai.

I explicitly encouraged the contributors to weave into their essays key stories about the people who played pivotal roles in their particular studies, and this deliberate reflection on the human dimension provides one of the unifying themes in the volume. However, the choice of whether the contributors wrote about collaborators, field assistants, park guards, local farmers, students, government officials, hunters, or other memorable personalities was entirely up to them. For some of the contributors, this meant acknowledging people who had influenced their career decisions or who have participated in their research and whose appearance in the accompanying photos (all generously provided by the authors) is testimony to the importance of their presence on the projects. For other contributors, the focus remained on the animals and how their behavior or circumstances have changed over time; nonetheless, when people do enter these stories, it is usually without names but with power or responsibility for imposing or communicating policies and official actions that impact the animals and the authors’ scientific plans. This diversity of interpretations of the assignment is extremely informative, as it illustrates the different social and cultural dimensions in which primate field researchers work.

MAP 1.1

The dynamics of the cultural dimensions of primatological fieldwork differ not only by place, but also over time. For example, when I first visited the forest at Fazenda Montes Claros, a private coffee plantation and cattle ranch in the municipality of Caratinga, Minas Gerais in 1982, I was a 23-year-old graduate student exploring the possibilities of studying the behavioral ecology of the muriquis for my Ph.D. research. All of my interactions—whether with the owner of the forest and his family, or with the local people who lived and worked on the surrounding lands, or with the Brazilian university students (my peers), their professor (who became my first official Brazilian sponsor), or the ex-hunter who worked as his assistant—were constrained initially and most obviously by my rudimentary knowledge of Portuguese. Many of those early interactions were also undoubtedly shaped by a suite of conventions attached to someone of my foreign nationality, age, gender, and (single) marital status. I remained only vaguely aware of these conventions, even after I returned in 1983 for the 14-month field study that marked the onset of what was to become the ongoing, long-term research and conservation project that it is today.

Along with habituating one of the two muriqui groups that inhabited the forest and then documenting the feeding, ranging, and unusually peaceful social patterns of the 23 individuals in the group at the time, that first 14-month stretch of fieldwork also set the foundation for friendships and collaborations with Brazilian researchers and some of the local farming families that have persisted over the years. However, whereas the clues to deciphering the muriquis’ unique egalitarian society and distinct way of life came from systematically observing their behavior while silently following them on their daily routines in the forest, my relationships with the people depended on my ability to communicate with them in Portuguese, on their patience with my frequent language lapses, and on our mutual efforts to find topics about which to relate.

Initially I sought refuge from awkward social interactions by spending as much time as I could in the forest. Those long working days at the outset were probably responsible for the rapidity with which the muriquis stopped fleeing and began tolerating my presence, and thus contributed to the advancement of my research goals. Although motivated at least as much by shyness as by dedication to the research, those long days in the forest also contributed to the reputation I soon acquired for working hard and for being apaixonado, (passionate) about the muriquis. The local people also worked long days, especially when there were crops (mainly coffee, beans, or sugar cane) to plant or to harvest, so this work ethic became something we had in common. We got to know each other in passing, especially early in the morning, along the dirt road that bisected the forest and that led me to my trails and the farmers to their fields.

My passion for the muriquis, by contrast, had a somewhat different effect than my long working days, for although it was a source of mild amusement, it also stimulated interest and curiosity about what could possibly be so special about the animals. The enigma was particularly puzzling to some of the kids, who were growing up in the countryside surrounding the forest but had no frame of reference with which to appreciate its importance as one of the last remaining sanctuaries for the muriqui and other endemic species of the Brazilian Atlantic forest ecosystem.

Today, this has mostly changed. By now, after three decades of research involving many dozens of Brazilian students and collaborators who have participated in the long-term monitoring of the 330-plus individuals in the entire population at this writing (now divided into four social groups), general knowledge about many facets of the muriquis’ behavior and ecology and an appreciation for the forest that supports them has spread. In 2001, the owners of the forest transformed it into a permanently protected nature reserve. Although the Fazenda still exists, the forest is now known as the Reserva Particular do Patrimônio Natural (RPPN) Feliciano Miguel Abdala, in honor of the individual who defended the muriquis from hunters and preserved the forest long before laws to protect endangered species and their habitats had been passed. The research on the muriquis and the conservation of the forest have attracted international media attention and documentary filmmakers, as well as journalists familiar to everyone in the region because of their celebrity status on Brazilian television and in the Brazilian press. No one is surprised anymore by these activities or the attention that the muriquis generate.

Conversations early on with Russell Mittermeier (currently President of Conservation International) and two of the pioneers in Brazilian conservation and primatology, Dr. Adelmar Coimbra-Filho and Professor Célio Valle, encouraged me to consider the many ways in which maintaining a long-term research presence could contribute to conservation. For example, employment opportunities associated directly with the research and indirectly through the conservation NGOs (including the Brazilian NGO, Preserve Muriqui, established to administer the Reserve) have been essential to the research infrastructure. Although it is difficult to evaluate the full effects on the local economy, these activities have been going on for the past thirty years. This has been long enough for children of our long-term employees to become the first in their families to graduate from college. Some of those curious kids I first met in 1983 have cleared trails, collected temperature and rainfall data, or monitored the camera traps we now use in the research; they also have guided tourists and film crews that visit the Reserve and have worked in the NGO’s nursery, where seeds of native tree species are collected and nurtured until the seedlings are ready to be sold for reforestation programs in the region. Many of those kids, now parents themselves, have invited me to their families’ weddings, birthdays, and funerals. I have known the people in this community for more than half of my life.

The same can be said for some of the muriquis, which were present in my original study group at the outset and are still alive. These surviving muriquis were among the first individuals I could identify on the basis of their natural fur and facial markings. Based on what we now know about female age at first reproduction, some of those original adult females carrying infants in 1983 would have to be in their mid-to-late 30s by now; based on the long-term monitoring of their extended genealogies, we know that at least some of these females now have great-great-great-grandoffspring in the population.

Unlike male muriquis, which remain in their natal groups for life, most muriqui females leave their natal groups at about 6 years of age, before the onset of puberty. For years, my students and I confirmed that the emigrant females were associating with other muriquis from one of what had grown to two other groups, but then we lost contact with them when we resumed observations on members of the main study group. By the late 1990s, however, curiosity about these females’ fates—and about the size and status of the rest of the primate population—led me and my long-time friend and collaborator, Sérgio Mendes (currently a professor at the Universidade Federal de Espirito Santo, or UFES), to organize a forest-wide census of the primate community with more than a dozen previous students who had worked on the project and were willing to donate a week of their time.

The census confirmed that there were as many muriquis living on the northern side of the forest as there were in our main study group in the south, and some of the females that had emigrated from the study group were still recognizable to the students who had spent years observing them. It was obvious that if we wanted to track individual females’ life histories from birth through their entire reproductive lives, and to monitor the size, health, and long-term viability of the population, we would need to expand our research scope. This was accomplished, initially, through the collaboration of a post-doctoral fellow, Jean Philippe Boubli, and some of the students who had previously worked with the main study group, including Carla Possamai (who joined the project in 2001 and now holds a Ph.D. from UFES). Since 2003, the entire population of muriquis in the 957-hectare (or 2,365-acre) Reserve has been monitored.

The muriquis’ endangered status has always played a role in my decisions about the kinds of questions to prioritize in the research and in my commitment to noninvasive research methods, which have included parasite, hormonal, and genetic studies based on analyses of the muriquis’ dung that we could collect and preserve when it dropped to the forest floor. But it was not until I began thinking at the level of the entire population, instead of concentrating on my long-term study group, that I fully appreciated the importance of understanding the dynamics of the demography underlying the long-term persistence of the population. This shift in my priorities was stimulated, in part, by documented changes in the muriquis’ behavior, which could most plausibly be attributed to the population’s growth and shifts in the age structure and sex ratios of the groups. This has led us to pursue new investigations into the plasticity in their social and ecological adaptations, including the expansion of the muriquis’ habitat use into an increasingly terrestrial niche.

With some 335 individuals (as of June 2013), our study population now represents more than one-third of all of the northern muriquis in the world. Its growth illustrates the promising potential of small populations to recover when they and their habitats are well protected. Our concerns now have shifted from the muriquis to include the constraints of the small size of the forest on further population growth. Now that the original forest fragment is protected for perpetuity, we need to find ways to increase its size. The most efficient way to do this is through the establishment of forest corridors, which the muriquis could use to move into other neighboring forest fragments.

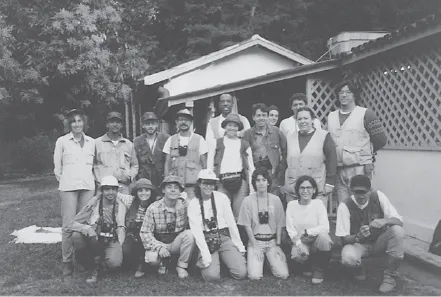

FIGURE 1.2A Some of the students and colleagues who participated in the first census of primates in 1999 at the RPPN Feliciano Miguel Abdala, in Caratinga, Minas Gerais, Brazil. The author (and the editor of this collection) is standing on the far left. Her collaborator, Sérgio Mendes, is standing in the middle row, sixth from the left (in a jacket). Photo credit: Courtesy of Karen B. Strier.

FIGURE 1.2B Commemoration of the twentieth year of the muriqui field study in 2002 at the RPPN Feliciano Miguel Abdala, in Caratinga, Minas Gerais, Brazil. The author (and the editor of this collection) is fifth from the left in the back row. Her collaborator, Sérgio Mendes, is standing in the back row, second from the left. Also mentioned in the text and visible are Jean Boubli (standing back row, far left) and Carla Possamai (far back row, second from the right). Photo credit: Courtesy of Karen B. Strier.

FIGURE 1.3 An aerial view of pasture outside the boundary of the Reserve. Efforts to establish corridors through these pastures, into other forest fragments, are underway to increase the habitat available to the muriquis. Photo credit: Carla B. Possamai.

Establishing these corridors is one of the primary initiatives bei...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- PART I: INTRODUCTION

- PART II: STARTING OUT

- PART III: SOCIAL COMPLEXITIES

- PART IV: COMPARATIVE LENSES

- PART V: CHANGES WITH TIME

- Appendix: Tables of Cross-Referenced Regions, Species, and Key Topics and Concepts

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Primate Ethnographies by Karen B. Strier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.