eBook - ePub

Governing the Metropolitan Region: America's New Frontier: 2014

America's New Frontier

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Governing the Metropolitan Region: America's New Frontier: 2014

America's New Frontier

About this book

This text is aimed at the basic local government management course (upper division or graduate) that addresses the structural, political and management issues associated with regional and metropolitan government. It also can complement more specialized courses such as urban planning, urban government, state and local politics, and intergovernmental relations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Governing the Metropolitan Region: America's New Frontier: 2014 by David Y Miller,Raymond Cox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Governing America’s New Frontier

The Metropolitan Region

We understand the “city” to be an important institution around which virtually all modern societies are built. As academics, it is our explicit responsibility to study the city. However, we face a dilemma: there are two very different definitions of the term “city.” In a sociological sense, a city is seen as an urban area where people live, work, and engage in interactions among themselves. Such a view is absent any legal context. When that legal context is added, a city becomes an entirely different concept. A city now has becomes a legal entity with chartered rights granted by the state, formal boundaries, and self-government. The second definition treats the city as a politico-legal institution: A “city” in the United States is “an incorporated urban center that has self-government, boundaries, and legal rights established by state charter.”

As a sociological term, “city” is interchangeable with “metropolitan region” in that both terms mean an urbanized area with many jobs and people living therein. When “city” is used a politico-legal sense, the terms are not interchangeable, even though the need to make more public decisions at the regional level is becoming self-evident. Today’s metropolitan regions have nascent characteristics of the politico-legal city. In this book, we will explore the use of the terms “metropolitan region” and “city” and how they are slowly converging into a hybrid concept of governance.

There are several reasons for this approach. First, the metropolitan region has replaced the city as the conceptual unit in which the majority of people live and business is conducted. Second, it allows us to better frame the discussion of the structured relationship between the institutions of government and governing. By that we mean there is a vertical relationship, in terms of the governing context created by the state in which the metropolitan region exists, and a horizontal dimension, or the relationship between the institutions of government that exist within a metropolitan region. As such, we offer the politico-legal definition of the metropolitan region as the formal and informal relationships between institutions of governing in the area. Brenner (2001) captures our perspective by calling the movement from city to metropolitan region a “new politics of scale.” The state is too big, the city is too small, the region is just about right.

The study of the governing of our metropolitan regions is framed by acknowledging a conceptual distinction between government and governance. There have been broad societal changes over the last half century that have had pronounced effects on how we think about and operate in our world. As those changes relate to the public sphere, we are moving from a paradigm centered on government to one centered on governing or governance. Governing is the act of public decision making and is no longer the exclusive domain of governments. Indeed, governments at all levels, nonprofit organizations, and the private sector now work together in new partnerships and relationships that blur sectoral lines. Private businesses, under contract to governments, deliver a wide variety of governmental programs. Conversely, governments are often managing more private sector firms than public sector employees. Nonprofit organizations, often representing organizations of governments, are partnering with governments, private firms, and other nonprofits to deliver services. Private foundations in many metropolitan regions utilize revenues generated from the private sector to finance public, private, and nonprofit organizations in addressing important regional public problems. Although not everyone would agree (see Norris 2001), the study of the metropolitan region seeks to understand the governance of a region while recognizing that governments are important building blocks of the region’s structure. From this perspective, each metropolitan region has a structure, and metropolitan regions, collectively, could be said to have different structures.

The metropolitan region exists within an older and more established framework of intergovernmental relations in which state and local governments have operated since before the founding of the United States. Think of a state government and the local governments within its borders as a complex network of parts and wires that somehow are supposed to work together, much like a sound system on which we listen to music, if all the wires are connected correctly. These systems, a sound system and governments, are similar in that they are complex sets of dynamically intertwined and interconnected elements. Each includes inputs, processes, outputs, feedback loops, all within an environment in which they operate and with which they continuously interact. Any change in any element of the system causes changes in other elements. The interconnections tend to be complex, constantly changing, and often unknown. This systems perspective is the overarching framework that will be used to explain state, local, and regional government in the United States.

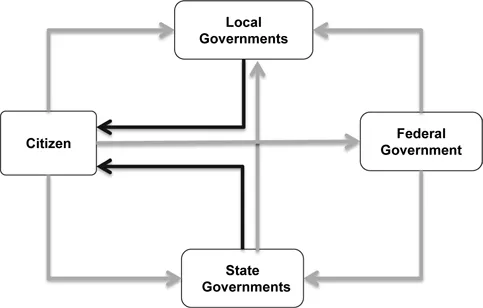

A model of this traditional system is presented in Figure 1.1. In this simplified presentation, there are four principal actors—the citizen, local governments, state governments, and the federal government. When we use the term “citizen,” we mean it in the broadest sense. It is meant to include citizens, local businesses, and other users of services, who also provide the financial resources to those governments. The term “local governments” is used to define localized governmental entities such as towns, cities, counties, special districts, and school districts.

Figure 1.1 The Traditional Four Principal Actors in the U.S. System of State and Local Government

As depicted in Figure 1.1, there is a fundamental structure to the intergovernmental governing system. That structure is made up of expectations, administrative networks, financial flows, and authority relationships such as state and federal mandates. While this figure looks orderly, it is better viewed as loosely structured relationships among the actors.

Put yourself in the box that says “citizen.” As a “citizen,” you have a set of expectations about what the world around you should look like. You expect to have some say in what that world looks like for you and others around you. To that end, you provide resources to various levels of government in anticipation that the government will be able to match your desired world. If you are like most people, you are not necessarily concerned with which level of government delivers the services, as long as they are provided. More frequently, you are not particularly concerned with whether the public, nonprofit, or private sector delivers the service. This is especially true for services generally considered as local.

Now, put yourself in the box that says “local governments.” From this vantage point, you receive an allocation of funds in the form of taxes and fees from the “citizen,” an allocation of resources from your state government, that may or may not have mandates attached, and some resources from the federal government. With those resources, you try to deliver a bundle of services that reflects the interests of your citizens, the state, and the federal government—not an easy task.

Move down and put yourself in the box that says “state governments.” From this vantage point, as with local governments, you receive an allocation mostly in the form of taxes from the “citizen.” You also get a fairly healthy allocation from the federal government that may or may not have mandates attached. With these resources you try to deliver a bundle of services to the citizens, either directly or through local governments. Sometimes, you make funds available to those local governments to be your agent in providing state services that you consider important. Other times, you provide funds to those local governments to help them provide local services they considered important. In either case, working with local governments, because they have their own resources, is complicated. Trying to maximize your resources from the federal government will help you achieve all your other goals.

Finally, move over to the “federal government” box. Here, you primarily administer a broad set of domestic policies through the provision of aid to state governments and, on a much more limited scale, to local governments. Under the constitution, you are in a compact with the states and the citizens. The states, each of which has its own constitution, have a legal relationship with their constituent local governments. As such, it is a challenge for you to deal directly with local governments without infringing on the role of the state government.

Life would be much easier if the simple model never varied. Although the model can generally be applied to each of the United States, there are 50 different and very distinct patterns of relationships—one for each state. Each state system has been evolving for centuries. They have become deeply institutionalized with relatively rigid formal and informal rules and expectations about how each government performs its responsibilities as a component in the system.

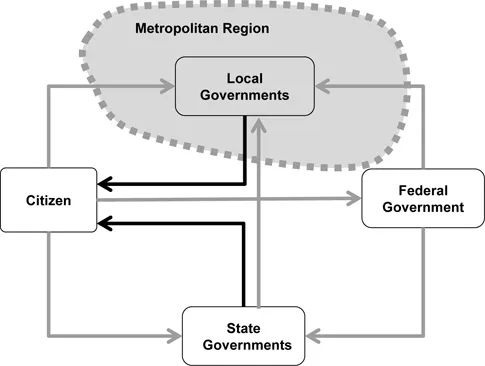

It is into this rich milieu of relationships that we now introduce a new player—the metropolitan region. The role of the metropolitan region is attached onto the existing patterns of relationships and is defined by them in the process. We have demonstrated this layering of the metropolitan region in Figure 1.2. We understand how the old system works, but we hardly understand the new system at all. We have used the oddly shaped depiction of the metropolitan region to reflect this lack of clarity in our understanding.

For instance, a line from the citizen to the metropolitan region is barely present, currently, in the system. Few, if any, regions have metropolitan-level officials and institutions that are known by citizens. The line from state government to the metropolitan region usually goes through institutions of local governments. The line from the federal government to the metropolitan region varies from federal agency to federal agency. One agency of the federal government, the Office of Management and Budget, defines metropolitan regions, but then warns against using those definitions for anything other than statistical applications. Conversely, the Department of Transportation has forced the flow of federal highway dollars through a designated metropolitan organization, generally utilizing the definitions supplied by the Office of Management and Budget.

Figure 1.2 The Traditional Four Principal Actors and a New Actor (the Region) in the U.S. System of State and Local Government

What we know about the metropolitan region could be answered as both “very little” and “fuzzy.” In this way, it represents a frontier. Even though our research into a better understanding of the structure of governance in a metropolitan region is, at best, emerging, the discussion about what an appropriate structure of governance should be is not new. Battle lines have been laid out for more than 100 years, and skirmishes have moved the line back and forth between notions of regions of many governments and regions of few governments. Conceptually, today’s discussion on how we manage a region is no different from yesterday’s discussion on how we manage a city.

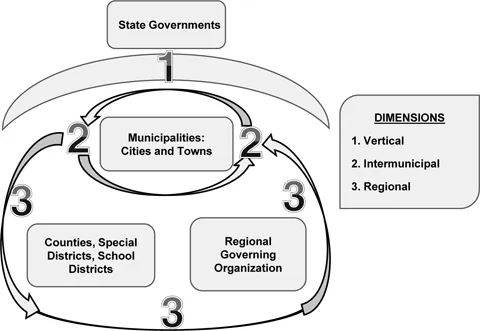

Figure 1.3 The Three Dimensions of Metropolitan Regional Governance in the United States

There is a structure to the patterns of relationships that exist within metropolitan regions (Miller and Lee 2011). This structure has three primary dimensions, as seen in Figure 1.3. The first is a vertical dimension represented by the number 1. We have used the symbol of the arch to reflect the overall responsibility that the state has for its territory. Virtually all of the activity that occurs under the arch falls within the domain of the state to define how it will work. As will be demonstrated, states have adopted a wide range of strategies relative to their treatment of local governing institutions. Some states take a relatively hands-off approach and leave much of the design and execution of local governing in the hands of localities. Other states take a relatively authoritarian approach and more directly control the design and function of local governments.

A second dimension is horizontal and involves the fundamental relationships between the municipalities within a metropolitan area. Municipalities, generally defined as cities and townships, are relatively equal in the eyes of the law and custom. They have grants of authority to undertake a number of functions, the power of taxation to implement the desires of its citizens, and the land-use authority to control the nature and direction of development within the community. Municipalities are the building blocks of metropolitan areas and their relationship (or lack thereof) to each other is the key variable in determining whether meaningful regional decision making can occur and how it will occur. We have represented this dimension by the number 2.

The third (represented by the number 3) is also horizontal but involves the fundamental relationships between important governing institutions within a metropolitan area. As such, it captures the emerging notion of metropolitan governance (see Foster 1997; Barnes and Foster 2012). In addition to local governments known as cities and townships, it includes the other principal types of local governments, such as counties, special districts, and school districts. Of the three, some county governments come closest to municipalities relative to function, taxation, and land-use authority. That said, and there are exceptions to the rule, it is seldom to the same degree of freedom as that of municipalities. The districts, special or school, will often lack at least two of the features associated with municipalities. First, they seldom have a broad functional role as they are most often confined to undertake one or two specific services. Second, few special districts ha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Commonly Used Acronyms

- 1. Governing America’s New Frontier: The Metropolitan Region

- 2. Creatures of Whom? The Intentionally Conflicted Nature of Local Government in America

- 3. The Evolution of the Financial Relationship Among State and Local Governments

- 4. The Primary Types and Roles of Local Governments

- 5. Fifty States, Fifty Different Systems

- 6. The New Kid on the Block: The Metropolitan Region

- 7. The Urban Core as Outward Region Building: A City and Its Contiguous Municipalities

- 8. Sharing Wealth and Responsibility: Fiscal Regionalism

- 9. Reshaping Counties and Integrating Regional Special Districts: High Risk but Great Potential

- 10. Representing the New Kid on the Block: Regional Governing Organizations

- 11. State Government Versus Local Governments: Creative Tension or Inherent Conflict?

- 12. The Conflicted Role of Professional Municipal Managers: Help Build or Insulate from the Metropolitan Region?

- 13. Speculation on the Future

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Authors