- 550 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This text provides a comprehensive introduction to the key personality theorists by combining biographical information on each theorist with his or her contributions to the field, including her or his ranking among the world's most respected psychologists. In addition, Allen provides a tabular format–that is, a running comparison between the major theorists, allowing students to analyze new theories against theories learned in previous chapters. The unique style of Allen's book is strengthened through his conversational tone, enabling students to easily grasp an understanding of the key people and movements in the field of personality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Personality Theories by Bem P. Allen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

• How is personality defined and measured?

• Are personality researchers scientists?

• What kinds of tests do personality psychologists use?

One goal of this first chapter is to answer the question “What is personality?” by providing a preliminary definition. Another is to consider how personality is studied and the kinds of tests personologists—personality psychologists—use. A final goal is to lay out the logic behind the structure of chapters.

Preliminary Definition of Personality

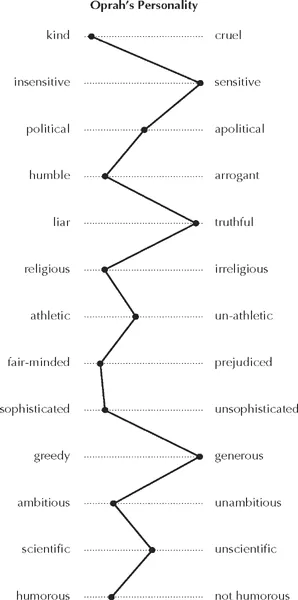

The preliminary definition of personality has several facets: individual differences, behavioral dimensions, and traits. Individual differences refers to the observation that people differ in a variety of ways. In the study of personality, the important differences involve personality traits, internally based psychological characteristics that often correspond to adjectives such as shy, kind, mean, outgoing, dominant, and so forth.

Each trait corresponds to one end of a behavioral dimension, a continuum of behavior analogous to a yardstick. Just as one end of a yardstick is anchored by 0 inches and the other end by 36 inches, one end of a behavioral dimension is anchored by one behavioral extreme and the other end by the opposite extreme. For example, affiliativeness, anxiousness, and conscientiousness are labels for behavioral dimensions. The following example shows the extremes for conscientiousness:

conscientious:1:2:3:4:5:6:7:unconscientious

One end of the assertiveness dimension is anchored by conscientious, the tendency to be neat, well organized, on time, efficient, and effective. The other end is anchored by unconscientious, the tendency not to defend one’s rights and to say “yes” when one wants to say “no.” For the sake of convenience and simplicity, the example has only seven degrees. In reality, the number of degrees of a dimension is difficult or impossible to determine. In any case, only behaviors falling near the extremes of dimensions have much meaning for personality. Only if a person’s behavior can be represented on the assertiveness dimension by a degree close to the anchor assertive can it be inferred that he or she possesses the trait conscientious. A trait dimension may be seen as the internal representation of a behavioral dimension.

Putting the facets together, an individual’s personality is a set of degrees falling along many behavioral dimensions, each degree corresponding to a trait. Note that, although some people may share a particular trait, there are individual differences in possession of the trait. Some people have it and others do not. However, sharing does not apply to entire personalities. There are individual differences in the sets of traits that people possess such that no two personalities are exactly alike. Figure 1.1 shows the personality of Oprah, a favorite of students. The line drawn from each degree (trait level) to each other degree is her personality profile. Given enough dimensions, every person’s profile will be different from that of every other person. The line connecting degrees on dimensions is the “personality profile line.” For the middle-of-the-scale entries, Oprah is not extreme enough to be “traited” on these dimensions. Thus, she has neither trait represented by the ends of these dimensions.

Implications and Cautions

There is a coincidence of personologists’ beliefs about personality and the common sense notions held by nonprofessionals or laypersons. First, many personologists and laypersons believe that an individual is quite consistent across different situations (his or her behavior is at about the same point or degree along the assertiveness behavioral dimension in one situation as it is in the next). This point of view constitutes the most basic assumption of our preliminary definition of personality. Second, where single dimensions are involved, individuals can be very similar or even identical. That is, two or more people can, on the average, exhibit about the same degree of a behavior, and, thus, possess the same trait. Third, the overriding agreement between personologists and the people they study is the shared belief in individual differences (Lamiell, 1981). Because there are individual differences along every behavioral dimension, given enough dimensions, personalities must differ. One respected estimate puts the number of traits and corresponding dimensions at over 17,000, thereby guaranteeing that each individual’s personality is different from that of each other person and, thus, that each person has a unique personality (Allport and Odbert, 1936).

Unfortunately, some people mindlessly assume that “individual differences” are immutable. If we view our positions on various dimensions—whether they are personality or intellectual dimensions—as “innate” and, thus, assumed to be unchangeable, our lives will be very limited. In an insightful article, Robert A. Bjork (2000) challenges the assumption that individual differences are set in stone. Basically, he takes on the widely held belief that we have or do not have valued characteristics the day we are born. That is, we tend to assume that our behaviors fall at the positive or the negative end of various behavioral dimensions, and, if the latter, that there is nothing we can do about it. If, according to one of Bjork’s examples, we fail a standardized math test early in elementary school, we assume that we are no good at math and should give up on it. “The role of [innate] aptitude is over-appreciated and the role of experience, effort, and practice are under-appreciated” (p. 3). We assume that we cannot, by our own devices, develop science aptitude, conscientiousness or the ability to appreciate others’ emotions, so we don’t try. Further, if we do assume that our behaviors occupy the “good” end of important dimensions, we are careful not to accept challenges, risk mistakes, or “think outside the box” lest we disprove our assumption that we are inherently gifted. I’ve known some honors students who assumed they were inherently smart, then avoided challenges and “out of the box” thinking lest they prove their assumption wrong. The result was mediocre work. I would add to Bjork’s points that the burning need to know may be more important to mastering some pursuit than all the “innate intelligence” we can claim for ourselves. Murray (2002) echos Bjork’s rejection of over-attention to “natural ability” and inattention to experience.

FIGURE 1.1 Oprah’s Personality

My experience as a personality researcher, reviewer of articles submitted to personality journals, and reader of personality publications tells me that the preliminary definition is implicitly, if not explicitly, adopted by more personologists than any other. It fits the theories of Murray, Cattell, Eysenck, and Allport rather well. All of them to some degree, at least implicitly, adopt its most basic assumption: a person behaves consistently from one situation to the next. These “trait theorists” must make the consistency assumption. Otherwise they would not be able to infer a trait from observations of a person’s behaviors. They reason if a person is assertive in one situation and not in the next, how could anyone draw an inference about whether he or she has the trait conscientious?

The consistency assumption, while widely adopted, is nevertheless not without its critics. Some theorists, such as Rotter and Mischel, reject it outright. I also have serious reservations about it. Other deficiencies of our preliminary definition include inattention to physiological and developmental processes. In view of these shortcomings, consider the preliminary definition to be a frame of reference against which definitions of the theorists covered in this book can be considered. You will find that each theorist has her or his own definition, in some cases fitting the preliminary definition fairly well, but not always.

Methods of Studying Personality

First, a set of criteria for evaluating methods of studying personality must be specified. As in other fields of psychology, science is a main source of standards. The minimum requirement for a research method to be called scientific is that it involve unbiased observations that are quantified so that systematic analyses can be performed (Allen, 2001). Methods can properly be called “scientific” if (1) they allow researchers to make observations without regard to their personal biases, and (2) they permit the assignment of numbers to those observations so that systematic analysis is possible. By contrast, users of unscientific methods base selection of observations on convenience—whatever happens to be handy is observed—or personal bias—the researchers arbitrarily believe that selected observations are more important than other observations they might make. In addition, users of unscientific methods may draw conclusions about what they have observed without reference to theory or previous research. However important such efforts may be for some purposes, the methods involved do not ordinarily qualify as scientific.

The Case History Method

The case history method involves collecting background data about and making intensive observations of a single individual in order to discover how to treat that person or to obtain information that may apply to other people (Rosenhan & Seligman, 1995). It may be scientific in that observations can be unbiased. After all, it is possible for psychologists to lay aside their own personal biases about personality. However, unbiased observations may be difficult for them because the person under observation may be a patient with whom the psychologists are personally involved. Also, observations made on a single individual may not be applicable to other persons. A given individual may be quite unusual and, therefore, not at all representative of other people. Further, although it may be possible to assign numbers to observations, systematic analysis may be difficult or impossible. For example, a psychologist may give personality tests to an individual and then derive some scores. Still, systematic analysis may be difficult because scores from more than one person are ordinarily needed to conduct a meaningful analysis.

Despite these shortcomings, case histories may sometimes qualify as scientific. It is possible to give the subject of a case history personality tests and then compare her or his scores to norms or average scores derived by testing large populations of people. In this way, how the case history subject’s scores compare to those of “people in general” can be determined and, thus, whether his or her score is unusual or like most people’s can be stated. Further, there have even been whole books written using a single case as the source of data for a statistical analysis in a scientific study (Davidson & Costello, 1969). Charles Potkay and I have actually used a single case to illustrate research results for our entire sample of research subjects (Allen & Potkay, 1973a, 1977).

While the case history method does not typically qualify as scientific, information derived from it may be useful in many ways. Reports based on observations of single individuals often are valuable as illustrations of personality functioning. While lamenting a lack of publications featuring case histories, Masling (1997) mused, “… it is a pity, because a good, carefully written and clearly documented case can be more instructive, and usually more interesting, than any number of research papers” (p. 261).

At a number of points in this text, many real and some contrived cases will be used to concretely illustrate some aspect of personality functioning. Box 1.1 contains an example that relates to a criticism of the working definition of personality: personality is not set in stone; it can change. Bearing these cases in mind will help you remember some of the important patterns that relate to personality theories.

Among this book’s case histories are some that you may find especially interesting: the Rat Man and the Wolf Man (and others, Chapter 2); characters in horror movies, delightful and mischievous Little Anna, and Bill Cosby (Chapter 3); an analysis of Frankenstein and his monster, based on the actual story by Mary Shelley (Chapter 4); the cases of Clare, a clingy, dependent woman madly in love with a self-centered man, and of the controller (Chapter 5); the good mother (Chapter 6); a hippie rebel turned conservative (Chapter 7); Hitler as a necrophilous (death-loving) character (Chapter 8); Becky and Dennis, Catholic and Protestant, coming to know one another in war-torn Northern Ireland (Chapter 9); a self-actualized person (Chapter 10); Jim and Joan, two college friends trying to resolve Jim’s conflict with a professor, and a cognitively simple person (Chapter 11); a person with an external orientation (Chapter 12); resilience in the face of defeat displayed by famous people (Chapter 13); a baby reared in a box (Chapter 14); dreams about the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby and an analysis of a disturbed college student (Chapter 15); a schoolgirl case of mass hysteria (Chapter 16); and the cases of Rinehart and Jenny and the mature person (Chapter 17). In addition, every theorist’s life story constitutes an often fascinating case history that begins every chapter.

In addition, your professor and you have a comprehensive case history in the Instructor’s Manual and in the Student Guide that accompanies Personality Theories (for the student guide see my Web site: www.wiu.edu/users/mfbpa/bemjr.html). The case history subject, Estella Monroe, is a young Latina mother who has survived a divorce and is “moving up the corporate ladder.” Estella’s relations with her son, her ex-husband, her new romantic partner, her coworkers, and her parents reveal material suitable for analysis by all the theories covered in this book.

BOX 1.1 • George Foreman: From Angry and Depressed to Joyful and Successful

I remember the earlier George Foreman well. I was and am a big Muhammad Ali fan, but at the time of the “rumble in the Jungle” (Zaire, Africa, 1974) Ali was past his prime and George Foreman was at his peak. Foreman appeared to be unbeatable. Joe Frazier had beaten Ali and Foreman “k...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Brief Contents

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Psychoanalytic Legacy: Sigmund Freud

- 3 Personality’s Ancestral Foundation: Carl Jung

- 4 Overcoming Inferiority and Striving for Superiority: Alfred Adler

- 5 Moving toward, away from, and against Others: Karen Horney

- 6 Personality from the Interpersonal Perspective: Harry Stack Sullivan

- 7 The Seasons of Our Lives: Erik Erikson

- 8 The Sociopsychological Approach to Personality: Erich Fromm

- 9 Every Person Is to Be Prized: Carl Rogers

- 10 Becoming All That One Can Be: Abraham Maslow

- 11 Marching to a Different Drummer: George Kelly

- 12 The Social–Cognitive Approach to Personality: Walter Mischel and Julian Rotter

- 13 Thinking Ahead and Learning Mastery of One’s Circumstances: Albert Bandura

- 14 It’s All a Matter of Consequences: B. F. Skinner

- 15 Human Needs and Environmental Press: Henry A. Murray

- 16 The Trait Approach to Personality: Raymond Cattell and Hans Eysenck

- 17 Personality Development and Prejudice: Gordon Allport

- 18 Where Is Personality Theory Going?

- Glossary

- References

- Name Index

- Subject Index