- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This innovative, interdisciplinary introduction to East Asian politics uses a thematic approach to describe the political development of China, Japan, and Koreas since the mid-nineteenth century and analyze the social, cultural, political, and economic features of each country. Unlike standard comparative politics texts which often lack a unifying theme and employ Western conventions of the 'state', "Political Systems of East Asia" avoids these limitations and identifies a common thread running through the histories of China, Korea, and Japan. This common thread is Confucianism, which has shaped East Asian perspectives of the universe and how it operates. The text describes and explains the ways in which each country has employed this shared tradition, and how it has affected the country's internal dynamics, responses to the outside world, and its own political development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Political Systems of East Asia by Louis D Hayes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

China

1

The Confucian Tradition

The recorded history of China’s civilization is not only one of the most extensive, it is also one of the richest in tradition. That this traditional civilization endured for millennia substantially unchanged is an experience without parallel. The long-term survival of China’s institutions is attributable in part to its physical isolation. Other parts of the ancient world that had achieved high levels of sophistication were not in contact with China, thus precluding intellectual cross-pollination. With few exceptions, China was untouched by neighboring cultures. In the sixth century B.C.E. in the Tarai region of Nepal, Prince Gautama contemplated the mysteries of life and in so doing attained enlightenment and established a religion. Buddhism spread throughout South Asia and was known in China by the second century B.C.E. It spread throughout the country by the second century C.E. and from China extended to Korea and Japan.

China was also spared the effects of conquest as it encountered few enemies throughout its long history capable of defeating, subduing, and transforming Chinese institutions and practices. In addition to its endurance, China attained impressive levels of accomplishment in all areas of human endeavor. Given these factors, it is little wonder that China regarded itself as the center of the universe, the “celestial kingdom.” Yet while it possessed an amazing capacity for survival, it was also inflexible. Ultimately, traditional China collapsed under its own weight, having in its last century become intellectually and institutionally petrified.

Confucius and the Chinese Way

It is customary to refer to the ideology of traditional China as Confucianism. Confucius supposedly lived from 551 to 479 B.C.E. The Confucian school of philosophy laid the intellectual foundations that would serve China for millennia. It was made the official ideology of the country during the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.).

The essentials of Confucius’s philosophy were simple. While he saw men struggling with each other everywhere, he refused to believe this situation to be a natural or proper state of society. Normal living is to cooperate, to promote common welfare. Social problems should be dealt with in a reasonable, moral fashion. Agents of the government ought to cooperate on behalf of the general welfare, which he defined as a pattern of harmonious relations. The ruler’s success should be measured by his ability to bring welfare and happiness to all people. To achieve these ends, Confucius favored government in the hands of virtuous, trained ministers chosen on the basis of merit. Superior men must rule. “It was a daring step for him to insist that the highest ministers should be appointed for their virtue and ability, regardless of birth.”1

Confucius

Confucianism’s rationale for organizing society began with the cosmic order and its hierarchy of superior-inferior relationships. Parents were superior to children, men to women, rulers to subjects. Each person therefore had a role to perform collectively as defined by convention, establishing a fixed set of social expectations. These expectations were defined by authority, which guided individual conduct along lines of proper ceremonial behavior. Confucius said, “let the ruler rule as he should and the minister be a minister as he should. Let the father act as a father should and the son act as a son should.” If all people conducted themselves according to their proper social role, all would be well. To do otherwise would not only bring on disorder but discredit. “Being thus known to others by their observable conduct, the elite were dependent upon the opinion and moral judgment of the collectivity around them. To be disesteemed by the group meant a disastrous loss of face and self-esteem for which one remedy was suicide.”2

In contrast to the Western Christian notion of the corruptibility of mankind, evident in the fall from grace idea, Confucius held to the principle that man is perfectible. In the Warring States Period (421–279 B.C.E.), the notion that men are qualitatively different at birth was replaced by the idea that men are by nature good and have an innate moral sense. Men can be led along the right path through education, and especially through their own efforts at self-cultivation. To this end they need to be provided with appropriate models to emulate. “The individual, in his own effort to do the right thing, can be influenced by the example of the sages and superior men who have succeeded in putting right conduct ahead of all other considerations. This ancient Chinese stress on the moral educability of man has persisted down to the present and still inspires the government to do moral educating.”3

Another important tenet of Confucius’s philosophy was a code of behavior that stressed the idea of proper conduct according to social status (li). There existed an elite made up of superior, noble men who were guided by li. The precepts of li were written in ancient records that became the Classics. The code was less relevant to the common people, whose conduct was to be regulated by rewards and punishments, rather than by moral principles. The code was essential for the elite, who were responsible for the management of public affairs. Confucius emphasized right conduct on the part of the ruler and those subordinate to him. The main point of this theory of government by good example was the idea of the virtue that was attached to right conduct. To conduct oneself according to the rules of propriety or li in itself gave one a moral status or prestige. This moral prestige in turn gave one influence over the people. “The people are like grass, the ruler like the wind; as the wind blew, so the grass was inclined. Right conduct gave the ruler power. Confucius said: When a prince’s personal conduct is correct, his government is effective without the issuing of orders. If his personal conduct is not correct, he may issue orders but they will not be followed.”4

In the hierarchical arrangement of society, everyone should know his place and the nature of his relationships with others. Everyone should serve the one above him and the one above should protect his inferior. Harmonious linkage of relationships creates obligations to maintain social bonds; these bonds are maintained by convention. There are no preconceived rules, only the ruling elite, the gentry, decide for the moment what is the right thing to do. “From the arbitration of disputes to the sponsorship of public works to the organization of local defenses, the gentry performed an indispensable function in their home areas.”5

In the West, the tradition was established during the time of the Roman Empire that there are objective rules governing behavior that are codified into law and enforced by the state. Over the past few centuries, the “Roman Law” approach has been augmented by the idea of a contractual relationship among consenting individuals. In the larger political sense, this took the form of the “social contract” that provided the theoretical basis of constitutions. Thus, in the West, rules are formal, legal, and mechanical. In East Asia, under the Confucian philosophy (and in most of the rest of the world in fact), rules are based on moral understanding.

Many in the West who wished to transcend the Old Testament idea of a vengeful God or the Hobbesian idea of the state as a mechanism to keep people in line, have been attracted to Confucius’s ideas. “Western observers, looking only at the texts of the Confucian classics, were early impressed with their agnostic this-worldliness,” write Fairbank and Goldman in China: A New History. “As a philosophy of life, we have generally associated with Confucianism the quiet virtues of patience, pacifism, and compromise; the golden mean; reverence for the ancestors, the aged, and the learned; and above all a mellow humanism—taking man, not God as the center of the universe.”6 This is by no means a radical philosophy although it does remove theology from the equation. “But if we take this Confucian view of life in its social and political context, we will see that its esteem for age over youth, for the past over the present, for established authority over innovation has in fact provided one of the great historic answers to the problem of social stability. It has been the most successful of all systems of conservatism.”7 At the same time, Confucianism did not try to make each individual “a moral being, ready to act on moral grounds, to uphold virtue against human error, even including evil rulers. There were many Confucian scholars of moral grandeur, uncompromising foes of tyranny. But their reforming zeal—the dynamics of their creed—aimed to reaffirm and conserve the traditional polity, not to change its fundamental premises.”8

Another important feature of Confucianism is the low status accorded to the exercise of coercive force, that is to say, the military. This does not mean there were no armies in traditional China; they existed, fought wars, and often shaped political events. But as compared with many periods and places in the Western experience, the military did not occupy high rank in social and political terms. In the later Roman Empire, the role of the military was decisive. In fact, the military was key to the establishment of the modern Western state and to the implementation of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western-style imperialism. In China, while there were large armies and frequent wars, the military as an institution never attained the prominence or permanence comparable to that of the civil service either in an organizational sense or as an enduring political force. The military was seen as a tool of policy rather than as an institution that creates or participates in the creation of policy. The status of the military is best expressed in the old saying: “Never make nails out of good iron, never make soldiers out of good men.”

It can be argued that China’s failure to appreciate the importance of military force as an expression of national interest accounts in part for its victimization at the hands of Western imperialists. Western militaries became highly innovative, while the military in China remained rooted in tradition. Nor did the Chinese military have a role similar to that of Western militaries. “Behind this lay the Confucian disdain for the military,” Fairbank and Goldman tell us. “So deep-laid was this dislike that the military were excluded from the standard Confucian list of the four occupational groups or classes—scholar (shi), farmer (nong), artisan (gong), and merchant (shang).”9

The political role of the military may have been circumscribed throughout China’s history, but military organization, strategy, and technical advancements far exceeded those of the West at the same period of time. Military studies such as Sun Zi’s On War, written in the sixth century B.C.E., continue to influence military thinking today. As is widely known, gunpowder was invented in China in the ninth century and was used against the nomad invaders. But this great breakthrough in military technology had little significance for the tradition-bound political system.”10

In addition to Confucianism, Chinese philosophy was enriched by other schools of thought. Among these was Taoism. This philosophy was contained in the Tao Te Ching, written about 240 B.C.E. While Confucianism was concerned with the individual and society, Taoism was concerned with the individual and the universe. Taoists advocated nonparticipation in social affairs. Man should return to primitive simplicity and seek harmony with natural law. Another early philosophy was that of the Moists, who advocated an all-embracing universal love that would remedy the ills of the world. This philosophy, five centuries before Christ, contained all the moral and ethical doctrines of Christianity except heaven and hell.

During the Qin dynasty (221–206 B.C.E.), a school of philosophy known as Legalism emerged. The Legalists stressed the importance of formal, rigidly authoritarian rules. While this approach did not endure, the notion of standardized rules fused with the more flexible, ethically driven philosophy of Confucianism resulting in a system where rules are made and enforced by conscientious and trustworthy men. Law was thought to be a normative guide to be applied with some degree of flexibility, depending on circumstances. Men were not equal before the law. The social order and traditional values rather than individual privileges had priority and needed protection by the state.

The Legalists believed philosophical disputation to be a waste of time, and to service this idea they set about burning all books. Only the authority of the state is meaningful. Man is evil and must be dealt with by the law and the authority of the state.

Science and Technology

One of the more striking things about traditional China was the disconnect between scientific learning and achievement and the application of those achievements in practical ways. Chinese inventions preceded similar ones by Europeans, in many cases by centuries. China invented gunpowder well before the Europeans did, but the latter made greater practical use of it. To allow discoveries and inventions to influence society by producing change would disrupt the fabric of harmony and stability. The static nature of China’s technological development is clearly expressed in a statement by R.H. Tawney: “China ploughed with iron when Europe used wood and continued to plow with iron when Europe used steel.”11

The long-term stability of China has often drawn the attention of historians. Immanuel C.Y. Hsu observed: “From 1600 to 1800, China’s political system, social structure, economic institutions, and intellectual atmosphere remained substantially what they had been during the previous 2,000 years. The polity was a dynasty ruled by an imperial family; the economy was basically agrarian and self-sufficient; the society centered around the gentry; and the dominant ideology was Confucianism.”12 But during the same period, the tradition-bound character of China left it ill-equipped to confront external challenges.

It is instructive to contrast the development of feudalism in Europe with China’s experience. The European system was based in part on mounted armored knights who depended upon a Chinese invention, the stirrup. The military utility of knights was ended by another Chinese invention, gunpowder. Why did no similar developmental pattern occur in China? “So deeply civilian was its ethos that the very conception of aristocratic chivalry was perhaps impossible,” Joseph Needham suggests.13 Moreover, institutionalization in the form of bureaucracy occurred early in China, precluding a feudal political pattern like that of Europe. And while, light cavalry like that of the Mongols was militarily superior to the heavy mounted knights of Europe, the military techniques of the Mongols were not those of the Chinese.

Although the Chinese invented the breast-strap harness, which enabled draft animals to pull heavier loads, again it was the Europeans who made significant use of it, not the Chinese. Use of horses, first domesticated on the Eurasian steppe, had a profound effect on European civilization. The horse is more efficient than the ox, and as a result, there was more crop rotation in Europe and a higher nutritional level. The social effects of horse-based development were profound.

One was a marked decrease in the expense of land haulage so that cash-crop produce could travel far more effectively than before; and a considerable technical development in transportation vehicles, notably four-wheeled wagons and carriages with improved pivoting front axles, brakes, and eventually springs. The other was more sociological and involved a proto-urbanization of rural settlement. Since the horse could move so much faster than the ox, the peasant no longer had to live in close proximity to his fields, and thus villages grew at the expense of hamlets, small towns at the ex...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

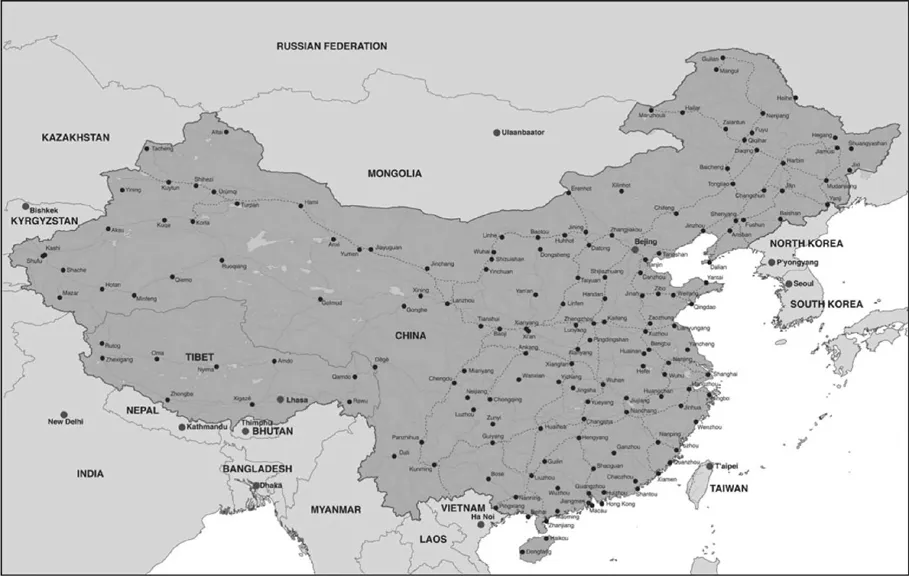

- Map of the Region

- Part I. China

- Part II. Korea

- Part III. Japan

- Appendices

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author