![]()

Part 1: The rise of the socialist city

Reassessing the capital

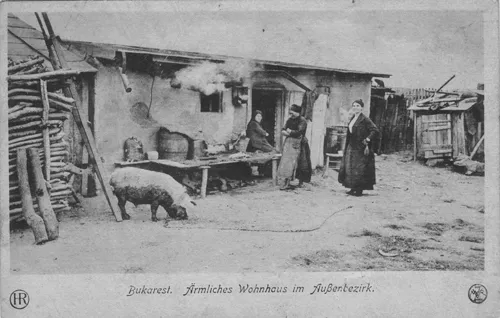

In 1947, the year when the Soviet-backed Communist Party came to power in Romania, the capital Bucharest was a sprawling settlement that had grown, within one generation, from a modest town into a bustling metropolis. Between the end of World War I in 1918 and the beginning of World War II in 1939, the population of Bucharest more than doubled, from 380,000 to 870,000, in the largest wave of urbanization in the city’s history. In 1948, the population stood at more than one million—a rate of growth that surpassed that of many other European capitals at the time. Along with the population, the territory of Bucharest expanded rapidly throughout the 1930s, almost doubling in size in an explosion of unregulated shack-towns around the historical center, put up rapidly and haphazardly to accommodate the population influx.1 As the infrastructure could not keep up with the distended urban fabric, vast swaths of this new, peripheral Bucharest subsisted without electricity, sewers, or running water. Despite their recent genesis, the new areas—and many of the older ones—had a surprisingly provincial atmosphere, with houses very modest in size—“one could touch their roof”—and small, enclosed gardens with flowers and fruit trees.2 Well into the fifth decade of the 20th century, even in the city center a visitor could still find exemplars of the 19th-century house type with its wooden porch and garden. Despite the boosterist label of “little Paris” that Bucharest carried in the 1930s, photos of the time also show dancing bears, ambulant sellers in regional costumes, roaming sheep, and a whole picturesque street life that somewhat contradicts the notion of a Bucharest of grand boulevards (Figure 1.1).3

Figure 1.1 “Poor Household on Bucharest’s Outskirts.” Postcard, 1930s (F. Volckmar, photographer.)

The new political elite regarded this capital with bitter dislike and proceeded to remake it into a different kind of city. In discussing the planning principles for the postwar development of Bucharest, the members of the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party (in Romania’s single-party system the body that held the political power after 1948)4 were constant in their disparagement of Bucharest’s condition. Meeting minutes of the early 1950s capture in candid terms the prevailing sentiment: “Bucharest grew like a spider, it is ugly, and almost three quarters of the housing in Bucharest are houses that cannot be used in the future. These need to disappear,” was the exasperated verdict of Petru Groza, the party’s General Secretary at the time.5

The same discussions also reveal that the political elites saw the socialist reconstruction of the capital as the responsibility of the highest level of government, and a task that reached well beyond the authority of the city council:

The Municipal Council of the Capital and the Communist Party Committee of the Capital give too little attention to the problem [of the redevelopment of Bucharest]. This is a problem that goes beyond the usual frame of reference, it is a problem for the state and for the government.6

The need to assess the condition of the capital prompted the Central Committee to order an extensive survey of its building stock, and a report presented by Pompiliu Macovei, chief architect of the City of Bucharest, detailed the inadequacies of the urban fabric in less impassioned but equally sobering terms: in 1954, 45% of residential buildings had neither running water nor sewer connection, and 25% were without electricity. Seventy-four percent of the city’s territory was covered in substandard construction that was either degraded or had been poorly built. It was also weakly settled, with single-level buildings covering 85% of the city’s territory.7 Such a city, in the eyes of the party, had to be radically transformed to allow it to fulfill its functional and symbolic role as the capital of a modern socialist state.

In many ways, what follows is the story of a professional and political class trying to effect, manage, and come to terms with modernization and urban development. The scenario of transformation was both universal and powerfully inflected by Romania’s unique circumstances, such as its anti-communist past but also especially its overwhelmingly rural identity, which had left its mark on patterns of urbanization. The communist political elites’ criticisms of prewar Bucharest were not just induced by a new political ideology; their roots ran back to the 1930s, when a professional consensus had started to take shape about Bucharest’s backwardness. A master plan commissioned by the Bucharest City Council in 1935 had come to similar conclusions about the cramped and unhygienic quarters of the urban poor, calling attention to their misery and terming their dwellings “cocioabe” (“hovels”). The postwar aversion to the historical city, however, now fueled by the Marxist-Leninist theory of class conflict, acquired an entirely new poignancy, and sharply recoded the capital’s urban fabric in terms of class differences and inequality. In 1952, one of the earliest official documents on Bucharest outlining the guidelines for its reconstruction, titled “Resolution Regarding the General Plan for the Socialist Reconstruction of the City of Bucharest,” began thus:

A striking contrast existed, on one hand, between the center and the neighborhoods of bourgeois villas, luxurious and comfortable, surrounded by parks and all necessary infrastructure, and, on the other hand, peripheral neighborhoods in which the working population piled up in small and unhealthy houses, living in misery and in extraordinarily harsh conditions, without running water, sewer, or electricity.8

In the propaganda-saturated language characteristic of those years, and before the more neutral term of “systematization,” or master planning, gained ground, the leitmotif of “socialist reconstruction” conjured up the image of a city in ruin. Bucharest had incurred relatively limited damage during World War II9 and therefore the term implied a recovery from the destruction inflicted on Bucharest not only by bombs, but also by decades of unregulated growth and the speculative pursuit of private profit. “Reconstruction,” in the Romanian context, was the battle cry of a project of radical urban transformation in which the “chaos and inequality” caused by capitalism would give way to a new, socialist spatial order.

Another remark on terminology bears making here. Bucharest’s working-class, poverty-stricken neighborhoods were often referred to by the Ottoman term of “mahala.” The Romanian provinces had been vassals of the Ottoman Empire until 1878, and cultural elites since the 19th century had viewed the legacies of a foreign dominant power in negative terms. In the 1950s, the designation of “mahala” therefore connoted a space that belonged to a defunct (and Oriental) world and enforced the cliché of backwardness. In contrast, when discussing modern neighborhoods, writings of the time used the term “cartier” or, after 1952 in the more specialized literature “cvartal,” both words of more recent import into the Romanian language, from French and Russian respectively, and with etymologies that aligned with different political and cultural values. (“Microraion,” a term applied to housing districts after 1960, further emphasized the technocratic and modern quality of the socialist settlements.)

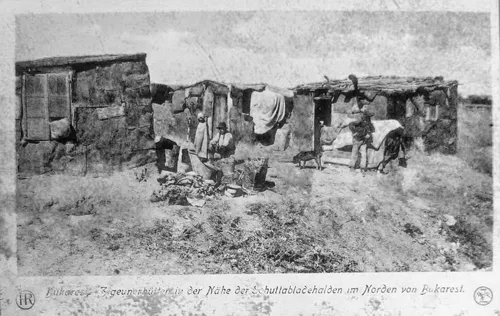

On the northern edge of Bucharest, not far from the elegant central boulevards, the neighborhood of Floreasca embodied, by the early 1950s, the characteristics of the mahala. Floreasca was bordered to the north by an infamous garbage dump (the “Floreasca pit”) that attracted a population of ragpickers and, in wintertime, families of “gypsies,” the nomadic Romany minority historically stereotyped as lawless and wild (Figure 1.2).10 Bordering the pit, a prewar development lay abandoned, a grid of streets with empty lots, which, in the writings of the time, served to illustrate another kind of wildness, that of unregulated or poorly planned urban growth. Against this background, between 1956 and 1963, the socialist state built modern apartment buildings, parks, and a host of public institutions and amenities. In the process, both architects and the emerging planning apparatus came to understand architecture as both a pragmatic endeavor and a narrative act that could recount the transmutation of a primitive settlement into a modern city, and of garbage into gardens. Visibly altered by socialist development, Floreasca shone brightly in the symbolic and political landscape of socialist Bucharest.

Figure 1.2 “Gipsy Household Near the Garbage Dump in the North of Bucharest.” Postcard, 1930s (F. Volckmar, photographer.)

Writers and commentators of the time also harnessed the illustrative, emblematic potential of the mahala and used it as a foil to a discourse of modernization. As in many other European cities at the turn of the 20th century, where reports about the living conditions of the working class became the motor of reform, the Romanian socialist state required its own accounts of the material and social afflictions of the bourgeois city it sought to reshape. As it formulated and debated new principles of planning and design, the socialist state also encouraged the outpouring of a literary genre that described, often in vivid and extravagant detail, the mud and chaos of the bourgeois city, and which provided a mythical point of origin for the coordinates of socialist architecture. A journal dedicated to the history of Bucharest, Materiale de istorie și muzeografie, became a regular outlet for such accounts throughout the 1960s:

Puddles formed at intersections and in the middle of dirt roads, in which pigs would freely bathe. The water, filled with waste, sweltered under the sun and exhaled pestilent smells, making malarial fevers endemic in these peripheral districts.11

Or:

To the city’s visitors, the center would appear with large boulevards bordered with elegant villas and tall buildings, while the periphery lacked all infrastructure. … This characteristic of the built environment in Bucharest perfectly represents the regime of exploitation. Between center and periphery, the bourgeoisie had erected insurmountable barriers.12

Even before its completion, Floreasca was insistently represented as an example of urban reinvention. In 1956, it provided the allegorical background for George Călinescu’s popular 1956 novel Scrinul Negru (The Black Chest of Drawers) and its extensive observation of the capital’s visible alteration. If, in the novel’s opening lines, Floreasca was a “wild place” with a countryside air, taken over by goats and “muddy sheep led by a shepherd,” at the end of the novel the reader finds “large public squares and wide interior courts that opened on perspectives like Renaissance architectural visions.”13 Călinescu used the figure of the architect to represent the new man under socialism who actively participated in the transformation of the c...