![]()

Chapter 1

The Health Centre Concept

Origins

Before the establishment of the National Health Service (NHS) in Britain, only manual workers (mostly male) were eligible for limited general medical services under the National Insurance Act of 1911. The Act made it compulsory for all manual workers to join health insurance schemes to which subscriptions were made by the employee, the employer and the state.1 The insurance companies each contracted the services of a panel of general practitioners (GPs) to provide a basic medical service to the insured, giving the arrangement the name 'the panel system'.

The concept of shared risk through insurance had been developed by Friendly Societies in some industries during the nineteenth century and this approach was adopted and expanded by the Liberal government as part of its welfare reforms of 1906-1914. But this arrangement still left the dependents of insured workers without adeguate support in times of illness. Women were especially exposed because of the sacrifices many made in order to feed their families, as were the young, the old, the handicapped and the unemployed.2 There were two different reforming responses to this problem. Some advocated rhe extension of National Insurance (NI) to cover the dependents of insured workers, while a number of more radical thinkers began to lobby for the eaablishment of a state health service to protect the whole population.3

Even for those who were insured, NI only provided access to see a GP and although the voluntary and poor law hospitals provided some acute care for the poor, this was limited in scope and distribution. Volimtary hospitals tended to accept patients with unusual and therefore interesting diseases and the workhouse infirmaries provided care in the most austere institutional circumstances to ensure that only the desperate would have to be supported by the Poor Law Guardians. Healthcare before the NHS was therefore available only to a proportion of the population and was for many either unaffordable or unavailable. Those who could afford to pay for care had access to their family doctor to provide general medical services but, if they needed inpatient care, had to rely on private nursing homes that offered only limited medical expertise.

The movement for reform was not only driven by humanitarian motives. The recruiting drives for the Boer War and later the First World War exposed the fact that a very large proportion of the population was not fit to serve in the armed forces. There was also concern, following events in Russia and across Europe in the early years of the twentieth century, that the dramatic contrast in income and living conditions between the rich and the poor would lead to social and political unrest and potentially revolution. This led to the recognition that in peace as well as war, Britain could not compete effectively with other countries without achieving some improvement in the health of its workforce. In addition, the growing effectiveness of both medical science and clinical practice inevitably stimulated demand for access to hospital services by those who could pay for treatment.

Proposals for the extension of NI or alternatively for the establishment of a state health service were developed by a number of different groups of progressive members of the medical profession, politicians and social reformers and led, at the end of the First World War, to the establishment of the Ministry of Health. The new Minister appointed three consultative committees to give him advice on the measures needed to improve health services: one representing the views of the medical profession, one the local authorities and the third the patient population. Arthur Greenwood,4 who was appointed as a member of the Consultative Council charged with representing the views of patients, drafted one of the clearest statements of the case for a state health service that has come down to us from that period.

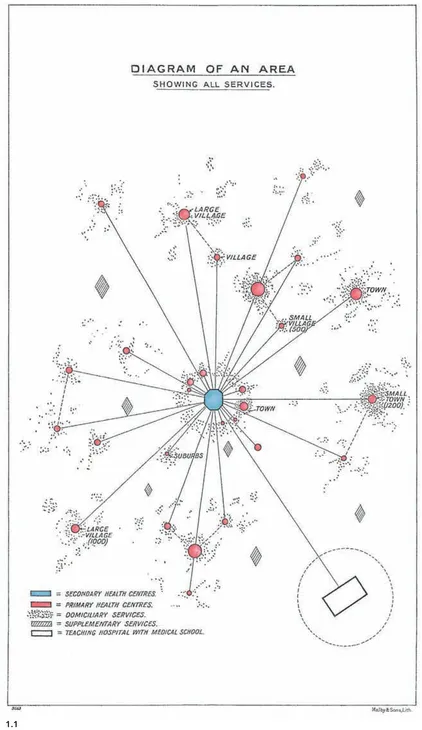

1.1 Diagram of the spatial distribution of facilities in a local healthcare system as envisaged in the Dawson Report of 1920. Hospitals in this diagram are called Secondary Health Centres (blue), and both large and small local health centres are called Primary Health Centres (red).8

'We hold strongly that the nation cannot afford to be without an effective public health service, that the preservation of human life and the conservation of human energy and the abolition of preventable disease and unnecessary suffering are essential to the wellbeing of the community. What the nation cannot with impunity allow are the far reaching effects of physical inefficiency and incapacity which reach upon every side of its social and economic life. The exercise of the responsibility of citizenship, motherhood, and employment are bound up with the health and vigour of the people. Our education system can yield its full fruits only when the school population is healthy. The ends of economy will be served not by crippling the public health service but by a wise and generous expenditure devoted to the provision of adequate health services which will conserve and develop the physical powers and energy of the people. To withhold financial resources from the public health service is a shortsighted policy striking at the foundation of the national welfare. The adoption of a comprehensive5 public health programme, on the other hand, will be abundantly justified by the immeasurable gains which would accrue in the social efficiency of the whole population.'6

At the same time, Dr Bertrand Dawson was appointed to chair the Consultative Council representing the views of the medical profession. His committee's report, which is known as the Dawson Report, was published in 1920 and contained detailed proposals for the coordination of local health services.7 The report set out the relationship between the different facilities that the committee suggested would be needed to deliver a coordinated health service (see Figure 1.1). These were to include teaching hospitals, local hospitals (called Secondary Health Centres in the report), and a new idea, Primary Health Centres, which were to be community facilities provided by local government and run by local GPs offering a range of primary care services.

The Dawson Committee's plan was impressive for its time, but many of the ideas it contained, including the concept of the health centre, were based on earlier proposals by others. It was, nonetheless, the first government-published document to advocate the use of the health centre as the focus for primary care in England and was one of the first texts in which the term 'health centre' was used.

Dawson's Primary Health Centres were intended to significantly expand the scope of GP activity. 'There would be accommodation for communal services such as those for pre-natal care, child welfare, medical inspection and treatment of school children, physical culture, examination of suspected cases of tuberculosis and occupational diseases, &c. These Services should, where possible, be aggregated at the Primary Centre ... . The communal services ... would, where possible, each be directed by a doctor (or more than one) practising in the area, such doctor having specially qualified himself for his post, The directorships of these communal services should be part-time posts paid on a time basis. For these services also, consultant advice should be available'9

In addition, each Primary Health Centre was to include patient wards and staff residential accommodation for nurses, midwives and district nurses working in the health centre and providing domiciliary services. The wards were included so that 'if in his judgment a patient could be more advantageously treated in the Primary Health Centie, he [the GP] would be able to arrange for the patient to be transferred there under his care.'10

The Dawson Report did not propose the inclusion of GPs' own surgeries in the Primary Health Centres,11 and the closest the committee came to advocating the establishment of GP group practices was the suggestion that 'Where local conditions, and medical opinion, favoured the plan, collective surgeries might with advantage be tried, either attached to a Primary Health Centre, or set up elsewhere',12 As well as confirming that GPs would retain their individual surgeries, the report proposed that they would run the health centres (on a part-time salary). Giving GPs access to the Primary Health Centres would give them the opportunity to expand their horizons and engage in team working. It would also extend the influence and ensure the autonomy of GPs and protect private practice.13

Dawson's Primary Health Centre was, in other words, to be a GP-run cottage hospital and would be supported by the Secondary Health Centre or local hospital and both would be provided by the local authority. 'The services of the Secondary Health Centres Would be mainly of a consultative type. The Centres would receive cases referred to them by the Primary Centres, either on account of difficulties of diagnosis or because in their diagnosis or treatment a highly specialised equipment was needful. On the other hand, Primary Centres would ease the work of the Secondary Centres by treating less complex cases which are now sent to the larger hospitals, and by receiving patients from the Secondary Centres when the acute stage of their illness had passed.14

Thus the Dawson Committee envisaged a new organisational structure in which three of the existing branches of medical practice — private practitioners, local authority clinics and hospitals — could all be accommodated and brought together in a coherent scheme. The financial basis of these proposals was not developed but it seemed to have been assumed that the Boards of Guardians would be abolished and the poor law infirmaries taken over by local authorities, private patients would continue to pay for medical services and the panel system, based on NI, would be extended to dependents. GPs would continue to work as independent businesses and would be able to treat both panel and private patients in their surgeries and in the Primary Health Centres.

'The Primary Centre would be the home of the health organisation and of the intellectual life of the doctors in that unit, Those doctors, instead of being isolated as now from each other, would be brought together and in contact with consultants and specialists; there would develop an intellectual traffic and camaraderie to the great advantage of the service. No doubt discussions and postgraduate instruction would in time be organised, and 'study leave' to teaching hospitals could easily and advantageously be arranged,'15

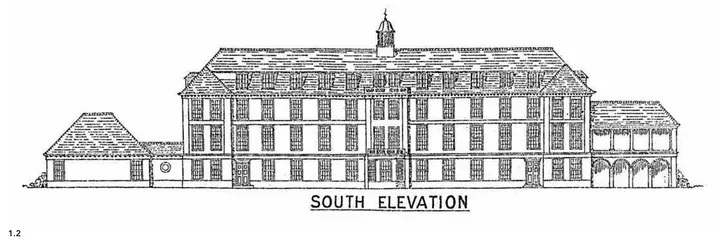

The Dawson Report presented a well-developed vision of how a coordinated health service might be organised. It not only established the idea of the health centre but also contained some of the earliest examples of health centre design. Plans for a small, a medium and a large Primary Health Centre were included in the report and show that these were to be quite substantial institutions. Figures 1.2 to 1.6 show the front elevation and plans of the Type 2 Primary Health Centre, which was described in the report as follows:

'This plan represents a building which would be suitable for the service of a small town or group of small towns or villages. In this building... the various rooms would be used at separate times for different purposes. Care has been taken, therefore, so to arrange the position of these rooms that they can be used for special examinations, if necessary, taking into consideration the various classes of patients who will use the Health Centre. It will be observed that a small labour and operating room has been provided on the Second floor, but it is not intended that this floor should be used entirely for maternity work, for which special buildings should be provided.'16

1.2 Dawson Report Primary Health Centre Type No. 2. Elevation.17

Given that these designs were one of the first attempts to visualise what was to be a new building type, they are enormously impressive. They are a precursor of the comprehensive health centre, proposed for the NHS at the end of the Second World War. The Dawson Committee's report was extremely influential and is referred to in discussions about health service organisation to this day. It represented, however, the views of the medical establishment and was a lobbying document designed to convince the newly appointed Minister of Health that improvements in healthcare could be achieved without resorting to the nationalisation of medicine and salaried employment for doctors.19 It was an ambitious attempt to improve healthcare by creating a unified local authority-run infrastructure to which independent contractors could have access.

This was, however, the inherent contradiction in the Dawson proposals. In order to ensure that the medical profession would not relinquish control of health practice to local authority committees and councillors, the report proposed extensive representation for the medical profession in the running of the local authority services, 'Nothing could have been more damaging to the prospect of local unification because such a demand ran directly counter to municipal policy ... "it is a principle of local government" local authority spokesmen repeated endlessly, "'that the people who spend public money should be publicly elected". Co-option the authorities might tolerate, but under no circumstances would they grant the doctors direct representation',20

The conservative nature of the Dawson Report can be clearly seen in the reluctance of the committee to commit the medical profession to entering salaried ...