![]()

Part I

Defining Site

Defining the site is the first architectural act. It may or may not be physical, but it requires action to define what a site is. This definition is significant for both pragmatic and conceptual reasons: something must be designed prior to conceiving of a building that can aid in understanding both functionally and conceptually the rationale for the building’s location. Places exist prior to (and after) site (this concept is elaborated on in by Robert Beauregard in his “From Place to Site,” listed in the bibliography). Places exist all around us, and are defined by our shared experience in them. You meet at a coffee house, you walk through a canyon, you visit the Eiffel Tower: these are all examples of places, and can be built or natural, designed or merely occupied. A place can be written about, photographed, discussed, walked through, and inhabited; it can be relatively well defined, but can also exist in comparable ambiguity. Site is distinct from this idea of place, because a site is a construct. It is what architects create, within which a design takes shape. The terms “place” and “site” are often used interchangeably by architects and in writings about architecture without intentionally being ambiguous, but this distinction is critical. The definition of a site is the beginning of a design. It is constructed in the mind of a designer, and must be used to communicate the framework within which an architect will operate.

![]()

1

Diagram

Diagrams are used everywhere in our daily life as a visual aid: in instruction manuals, for life safety, and for way-finding, to name a few. They help visually communicate the unfamiliar in a concise and elementary way. The diagram is, in its broadest sense, a representational tool used to reduce complexity to essential components and communicate critical relationships or tasks. But how does this relate to defining a site? Mark Garcia, in The Diagrams of Architecture, defines the diagram as it relates to architecture as “a spatialisation of a selective abstraction and/or reduction of a concept or phenomena. In other words, a diagram is the architecture of an idea or entity.”1 His definition applies a broad understanding of the diagram as a representational tool to architecture as a specific selective and reductive process that occurs in the mind. Defining a site is also essentially a process of reduction that occurs in the mind: it distinguishes the surroundings from everything there is. This reductive process is also highly selective, reducing the surroundings to what an architect determines are its essential components, and this is where the diagram becomes a critical tool.

Simon Unwin, in his book Analysing Architecture, describes the first architectural act as “The place where the mind touches the world.”2 It is, for him, an inherently human thing (in the Cartesian sense) to take in your surroundings, as well as the initial conceptualization of architecture. Unwin goes further in Analysing Architecture to outline his description of the basic elements of architecture—essentially building blocks from which all architecture derives. As with Garcia’s definition of the diagram, Unwin creates a spatialization of a selective abstraction. Like a Lego set, these building blocks are an abstraction of future construction. Intriguingly, Unwin begins with the ground, and the ground frames each of the basic elements:

The definition of an area of ground is fundamental to the identification of many if not most types of place. It may be no more than a clearing in the forest or it may be a pitch laid out for a football game. It may be small or stretch to the horizon. It need not be rectangular in shape nor need it be level. It need not have a precise boundary but may, at its edges, blend into the surroundings.3

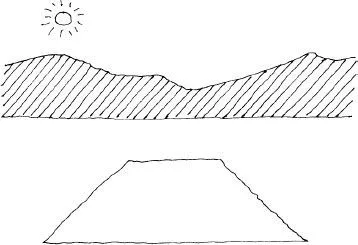

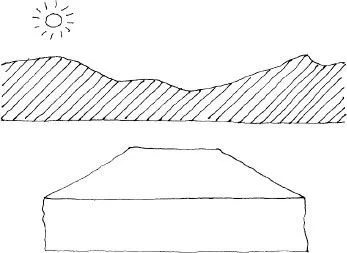

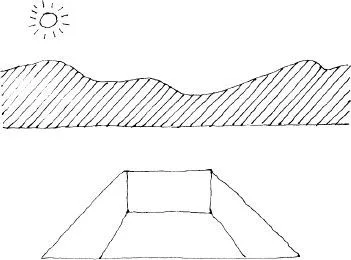

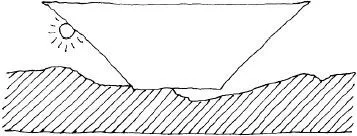

Because he begins with the ground, Unwin’s elements can also be a way of defining the site. For instance, the “area of ground” diagram shown in Figure 1.1 is both a building block and the more metaphysical locating of a site. It is a rectangle placed in perspective, in relationship to a horizon. The diagram conveys a site that is bounded, and within that boundary contains everything necessary to create architecture. In his “platform” diagram (Figure 1.2), Unwin then extrudes the defined area of ground, so that it is still inscribed by the initial rectangle in relationship to the horizon, but this area now has a form. In the “pit” diagram (Figure 1.3), Unwin reverses the extrusion of the defined area of ground to show a void. Again, the horizon is kept, as well as the initial rectangle, but through its absence the void creates a form again defined by the ground. His “roof” diagram (Figure 1.4) repeats this idea once again: it relies on the same horizon and the defined area, but the rectangle has now lifted off the ground to imply the area beneath.

In all cases, these diagrams depend on our perception of the horizon and perspective within the diagrams to literally “ground” the object described against the background. All of Unwin’s basic elements maintain a connection to this imaginary ground that exists somewhere between the foreground and the horizon. Unwin’s descriptions for each element of architecture are deliberately open-ended to allow for the greatest variation for potential architecture built from these elements. His diagrams are, on the other hand, measured and concise. They seek to visualize the smallest amount of information necessary to convey the idea. You can imagine that the defined area of ground could be a rectangle, but because it is a diagram, and from Unwin’s description, you know that the rectangle represents all possible configurations of an edge. The written definition acknowledges the possibility of blurring the edges, but the diagram refuses. The rectangle is concise and simple, but it is also an abstraction of all boundaries. The definition of the site is contained within the boundaries of that abstracted rectangle—it is literally bounded. Regardless of the blurring that occurs, the site has edges.

1.1 Defined area of ground. Simon Unwin, 1997.

1.2 Raised area, or platform. Simon Unwin, 1997.

1.3 Lowered area, or pit. Simon Unwin, 1997.

1.4 Roof, or canopy. Simon Unwin, 1997.

Stan Allen, in Points + Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the City, seeks “an architecture that leaves space for the uncertainty of the real.”4 Like Unwin, Allen is seeking to define (or redefine) architecture: how we go about it, and what it is. Allen uses the city to define the parameters around which architecture can happen, distinct from a more abstract notion of ground. Borrowing a concept from the physical sciences called “field conditions,” which is used to understand the complex, changeable and dynamic forces only seen by their effects, he creates a definition of site that exists without edges. For Allen:

a field condition could be any formal or spatial matrix capable of unifying diverse elements while respecting the identity of each. Field configurations are loosely bound aggregates characterized by porosity and local interconnectivity … Form matters, but not so much the forms of things but the forms between things.5

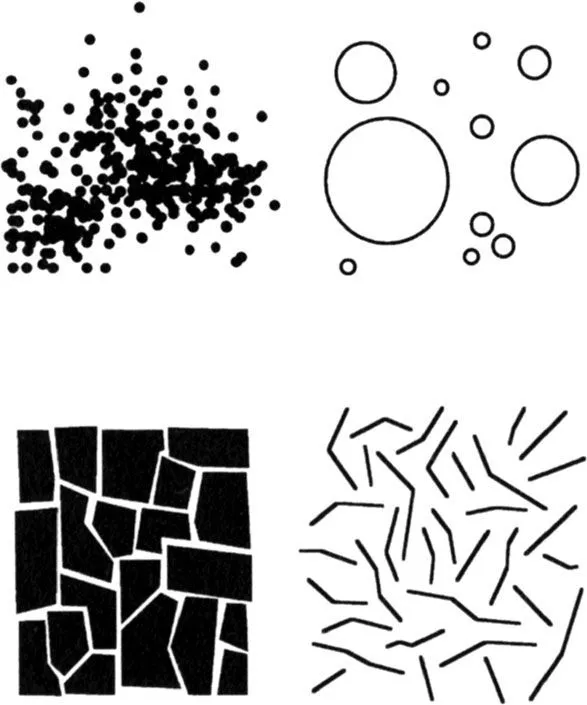

To illustrate what a field condition is, Allen avoids a concise diagram to literally inscribe varying notions of edge. Instead, he resorts to a series of diagrams to provide examples of what field conditions are (Figure 1.5). When examining this matrix, there are distinct commonalities: each show a clustering of black shapes that read together, in part by an implied boundary, but also because they form a kind of pattern. There is also a sense of balance, a kind of gestalt, between the amount of white and the amount of black in each diagram, where the black objects compete with the white figure formed by the black objects. The site is essentially defined by recognizing the pattern or the field condition in the surroundings; its limits are set by the emergence of the pattern, not by a containing boundary. For Allen, it is the relationships between things not the things themselves that define the site.

1.5 Field conditions diagrams. Stan Allen, 1999.

Both Unwin’s and Allen’s conceptualizations are equally effective and powerful definitions of a site: one set of diagrams should not be privileged over the other. They both seek to conceptualize architecture through site and by diagramming. Robert E. Somol, in his introduction to Peter Eisenman’s Diagram Diaries, discusses the nature of the diagram: “unlike drawing or text, partis pris or bubble notation—it appears in the first instance to operate precisely between form and word … it is a performative rather than a representational device … it is a tool of the virtual rather than the real.”6 The performative nature Somol describes is the key to understanding why diagramming should be considered when defining the site. The diagram should perform: it is a device that acts between things and words. Like Unwin’s sentiment that “architecture is where the mind touches the world,”7 the diagram is active as a tool of the virtual (outside the real). The author can select what to abstract and then abstract it, but the diagram has the power to communicate something about what it represents, as well as the power to change the way the author thinks. The performative nature to the diagram can be seen in the way both authors rely on written descriptions to clarify their diagrams. The diagram, without explanation, could represent many things to someone viewing it. Their descriptions allow for your perception to be shifted to see what they intend you to see. For both authors, the diagrams also clarify the idea behind the diagram, allowing the possibility that the authors learned something by generating it.

The definition of the site is fundamenta...