![]()

1

LEARNING A THEORY OF MIND

Henry M. Wellman

In 1990 I was invited to talk on the then-new topic of “theory of mind” at a gathering of developmental scientists from Australia and New Zealand (the forerunner of today’s meetings of the Australasian Human Development Association). Unknown to me, my invitation was masterminded by Candi Peterson, whom I met there for the first time.

Our next conversations were sparked by Candi’s groundbreaking study, “Deafness, conversation and theory of mind” (Peterson & Siegal, 1995). Until then, discussion about serious delays in theory-of-mind understandings had focused on autism and had served to provide support for nativist, modular accounts of theory-of-mind development more generally. From such a perspective, the rapid development of person understandings apparent in normal children worldwide, revealed in an understanding of false belief, reflected a specialized theory-of-mind mental module (ToMM) “coming online” in early development. From this neurological-maturational perspective (Leslie, 1994; Baron-Cohen, 1995), ToMM could be intact or it could be impaired, as apparently occurred in individuals with autism. An additional implication of positing this sort of theory-of-mind module, however, is that individuals who are not impaired in the relevant module or modules should achieve mental-state understandings on a roughly standard maturational timetable.

This is where the studies of deaf preschool children raised by hearing parents have been so revealing. As charted first by Candi and then by others, deaf children of hearing parents show delays and deficiencies on theory-of-mind tasks comparable to children with autism. Yet these deaf children have not suffered the same sort of neurological damage that autistics have. Their damage is peripheral – in the ears, not the mind. This is clear in the fact that deaf children raised by deaf parents do not show theory-of-mind delays. Findings such as these challenge accounts of theory-of-mind development relying heavily on neurological-maturational mechanisms and instead underwrite learning accounts of that development. Theory of mind develops dependent on the social-interactive experiences of the child, and it is this perspective that informs the current volume. A hallmark of these social-interactive experiences is that they can differ according to the child’s circumstances – his/her social context.

After that 1995 article, communication between Candi and me accelerated because we both favored an experiential-learning account of theory-of-mind development over a nativist, maturational one. Then in 2005 I was able to visit with Candi in Australia for three months. That visit sparked collaborations that produced much of the research I will emphasize in this chapter. Since my focus here is experience-dependent learning, it is fitting to emphasize at the start how much my own learning has benefitted from the experience of knowing and collaborating with Candi Peterson.

As a final piece of background, my first visit to Australia coincided with the release of The Child’s Theory of Mind (Wellman, 1990) and the current chapter follows on from the publication of its sequel, Making Minds: How Theory of Mind Develops (Wellman, 2014). A fuller treatment of the ideas sketched here is available in that book.

Theory of mind, in brief

Philosophers (Churchland, 1984; Fodor, 1987) and social scientists (D’Andrade, 1987; Wellman, 1990) have long agreed that theory-of-mind reasoning is organized around three large categories of mind and behavior: beliefs–desires–actions. Because people have beliefs and desires they engage in intentional actions. Or, in everyday thinking, we construe people as engaging in acts they think will get them what they want. Because Romeo and Juliet want to be together, but believe their families will violently disapprove, they proceed to see each other in secret.

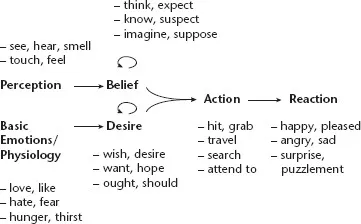

Beyond beliefs, desires and actions, theory-of-mind reasoning includes other important constructs and connections, such as those depicted in Figure 1.1. Romeo loves Juliet so wants to be with her. But Juliet is a Capulet and Romeo has seen his family’s hatred of the Capulets so he thinks they will violently disapprove. That’s why he tries to meet Juliet in secret. And when successful, Romeo reacts with happiness, indeed, he’s ecstatic and lovestruck; when unsuccessful he’s sad, dejected and forlorn.

Figure 1.1, then, sketches a framework for thinking of multiple sorts of theory-of-mind reasoning. Note that this is a very general framework. What, exactly, are Romeo’s beliefs and desires? This framework does not tell us. Shakespeare tells us, but a framework like that in Figure 1.1 only says Romeo has some beliefs and desires (and emotions and perceptions), and they’re important.

False belief

Beliefs play a special role in the framework shown in Figure 1.1. We construe agents as engaging in acts they think will get them what they want. Of course, they can be mistaken. And when mistaken, agents not only think wrongly, they act wrongly. At the end of Shakespeare’s play, there is Romeo down in the crypt with Juliet right beside him alive and well. Romeo kills himself. Why? Because he thinks Juliet is dead. This slippage between mind and world is an essential feature of theory of mind, and is one reason there has been so much research on children’s understanding of false beliefs.

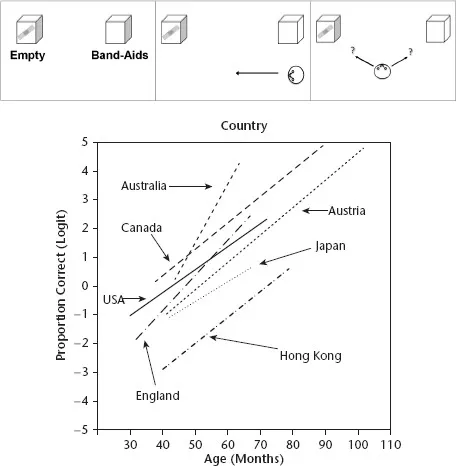

Box 1.1 sketches a common, “standard” false-belief task – one that deals with unexpected contents (also see Appendix). As outlined in Box 1.1, in several meta-analyses of hundreds of studies (Wellman et al., 2001; Milligan et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2008), 4-year-olds, 5-year-olds and 6-year-olds consistently answer correctly, like adults. These meta-analytic data clearly show early achievement coupled with developmental change. By 4 and 5 years many children are largely correct; on a vast array of false-belief situations they judge and explain correctly. But there is also clear change. By going backward to 2 and 3 years there is consistent below-chance performance, that is, classic false-belief errors.

Box 1.1

False belief tasks have children reason about an agent whose actions should be controlled by a false belief. Such tasks have many forms, but a common task employs unexpected contents, as depicted above. The child (not shown below) sees the two boxes and explores them to find the Band-Aids are in the plain, nondescript box, not in the Band-Aid box. Then she is asked about her friend Max, who has never seen these boxes before: “Max wants a Band-Aid, where will Max go for a Band-Aid?” Or, “Which box will Max think has Band-Aids?” Older preschool children answer correctly, like adults. Younger children answer incorrectly; they are not just random, they consistently say Max will search in the plain box (where the Band-Aids really are). Note that the task taps more than just attribution of ignorance (Max doesn’t know); rather it assesses attribution of false belief (Max thinks – falsely – Band-Aids are in the Band-Aid box).

A frequently used alternative task uses change of locations (rather than unexpected contents). See Appendix for details.

Several task factors make such tasks harder or easier, but nonetheless children go from below-chance to above-chance performance, typically in the preschool years. Moreover, as shown in the graph above (combining results from Wellman et al., 2001 and Liu et al., 2008), children in different cultural-linguistic communities can achieve false belief understanding more quickly or more slowly, yet in all locales they evidence the same trajectory – from below-chance (below zero in this graph) to above-chance performance in early to later childhood. This is true even for children growing up in non-Western cultural communities speaking non-Indo-European language. And it is true even for children in traditional, nonliterate societies.

Perhaps more interesting, the graph in Box 1.1 organizes the data by the country where the children lived and were tested. Across countries, cultures, and their related languages there are some differences in timetables – some children in some locales come to understand false belief a bit faster, some slower – but granting that, there is very similar conceptual development in all countries. To be clear, these sorts of childhood data do not mean that adult folk psychologies worldwide are equally similar, or that cultural construals of mind all look exactly like the Euro-American one which inspires Figure 1.1 (see Luhrmann, 2011; Wellman, 2013). Nonetheless, it is also true that in some culturally appropriate form or another, just as shown in Box 1.1, young children everywhere come to understand that a person’s actions are importantly controlled by what he or she thinks and intends, not just reality itself.

Infant “false belief”

A picture like that in Box 1.1, of false belief development as concentrated in the preschool years, represented the consensus view until about 7 or 8 years ago. But since then, as is well known, multiple findings have emerged claiming that even 12-, 15-, and 18-month-olds understand false belief. These data come from infant looking-time studies (Onishi & Baillargeon, 2005; Surian et al., 2007; Scott & Baillargeon, 2009), but also from anticipatory-looking, eye-tracking methods (Southgate et al., 2007; Neumann et al., 2008), and from studies using active–interactive paradigms where infants hand objects to others or otherwise actively interact with them (Buttelmann et al., 2009; Southgate et al., 2010).

For several reasons, I will not tackle the infant false-belief data in this chapter. First, I do so at length in Wellman (2014), where I make clear that we are far from a clear understanding of infant theory-of-mind development (see Morgan, Meristo & Hjelmquist, this volume). And second, importantly, it is the preschool conceptual developments (as in Box 1.1) that are directly related to children’s everyday life, actions, and interactions.

As is clear in Box 1.1, there is significant variation in timetables across countries in preschool achievement of theory of mind. Not directly obvious in that graph is that there is considerable variation across individuals as well. Although almost all normally developing children eventually master false belief, some children come to this understanding earlier and some later. This variation has helped researchers confirm the impact of achieving preschool theory-of-mind understandings. Children’s performance on false-belief tasks is just one marker of these understandings, but differences in false-belief understanding alone predict how and how much preschool children talk about people in everyday conversation (e.g., Ruffman et al., 2002), their engagement in pretense (e.g., Astington & Jenkins, 1995), their social interactional skills, including secret keeping (e.g., Peskin & Ardino, 2003) and lying (e.g., Lee, 2013), and consequently their interactions with and popularity with peers (e.g., Watson et al., 1999; Diesendruck & Ben-Eliyahu, 2006; Fink et al., 2014; see Slaughter et al., 2015, for a meta-analysis). False-belief understandings predict such social competences concurrently and longitudinally and do so even after IQ and executive function skills are controlled for.

These findings importantly confirm theory of mind’s real-life relevance and moreover they demonstrate that something definite and important is happening in children’s theory-of-mind understandings in the preschool years. Clearly, theory of mind has a foundation in infancy, but open questions remain as to how and why these understandings originate and change over time. For now, preschool data provide the best look at these developmental questions.

Theory theory

My approach to the preschool data, to theory of mind, and to much of cognitive development goes by the name theory theory. Theory theory has this name, because it is a theory proposing that children are constructing theories of the world from their evidential experiences. In this way, theory theory is an heir to Piaget’s constructivist account.

According to theory theory, human cognizers not only have coherent, framework representations of the world – like the framework outlined in Figure 1.1 – in the course of development we acquire these representations, they are learned. Theories and theory development, then, depend on a crucial interplay between hypotheses and data – between theory and evidence – that propels development. We use theory and data, together, to learn and revise more specific theories and framework ones as well.

I advocate theory theory, but the central claim – that cognitive development proceeds like theory development – raises a crucial question: how could this sort of learning be possible? Lack of a satisfying, clear answer undermined Piaget’s constructivism; it has been a weakness of theory theory as well. However, over the last 10 years things have changed due to theoretical and computational advances in learning. Of particular relevance to theory theory are advances in computational models that explore and exploit probabilistic Bayesian learning and especially hierarchical theory-based learning (e.g., Tenenbaum et al., 2006; Griffiths et al., 2010; Goodman et al., 2011). As Alison Gopnik and I argued (2012), these advances promise to reconstruct constructivism, and reinvigorate theory theory.

These computational approaches are Bayesian because they take off from Bayes’ law:

P (H/E) ∝ P(E/H) P(H)/P(E)

Bayes’ law is a simple formula to relate together two things: the probability of a hypothesized structure (H) and ...