![]() Section Two

Section Two

Treatment![]() Part A

Part A

Women’s Major Sexual Concerns![]()

5

Clinical Challenges of Sexual Desire in Younger Women

Rosemary Basson, MD, FRCP (UK)

My inability to do more than empathize with my patients as they told me about their sexual difficulties prompted me years ago to move from family and internal medicine to sexual medicine. My mentors had advised me not to teach our medical students about low desire because it was untreatable. However, the majority of female patients referred to our clinic complained about loss of desire—their “low libido.” I came to question basic matters: Was low desire a sexual disorder? Was it untreatable?” What did “low libido” mean?

Speaking to women with and without sexual difficulties made some themes apparent. The overriding motivation to be sexually active with a partner was to sense emotional closeness. Incentives such as feeling more committed, enjoying becoming more tolerant of each other’s imperfections subsequent to sexual activity, and feeling “normal,” attractive, and desirable were all in the mix. I also learned that the adequacy of sexual stimuli and the sexual context were vital. Being unable to focus on the moment, on the sexual stimulation and its attendant emotions, along with self-monitoring and thoughts of inadequacy, was a frequent problem. With little desire, some women would be avoidant, even aversive, by deliberately being busy or needing to go to bed earlier than the partner—or even allowing interpersonal disagreements to fester so as to lessen the partner’s sexual motivation. Others would limit activity to penile vaginal intercourse—“I want him just to get on with it”—while they remained unaroused. Gay women would revert to simply pleasuring the partner such that the interaction was totally non-mutual. However, it also became clear to me that many sexually content women were able to slow the pace, explain the caresses they needed, and recognize the contexts that triggered arousal and ultimately orgasm even though they too did not start out with a sense of urge/“passion.” After 10 years of listening to women’s sexual experiences and presenting these themes to colleagues at conferences and hearing their feedback, I published a model of sexual response to reflect women’s (as well as men’s) sexual experience, which became known as “Basson Cycles.”

Introduction

The majority of your patients with depression, even in remission, have difficulties with low desire. Less than 10% of women referred to our provincial sexual medicine clinic for low desire are not on antidepressants. Large cross-sectional and longitudinal studies confirm mood and feelings for the partner to be the major determinants of women’s sexual desire. You already have the skills to sensitively assess a woman’s developmental, interpersonal, and sexual history. You also are already using important treatment modalities, namely, cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. By becoming familiar with the current understanding of sexual motivation and sexual response you will be able to assess and manage her complaints of low desire.

Attempting to understand what each woman means by “desire” is challenging. Lack of sexual hunger or urge is not usually the issue. Women know that these urges typically lessen with duration of relationship and with age, and that they are not their main source of sexual motivation. Their other reasons to engage sexually are dependent on a rewarding sexual experience. Despite the words “low desire” the issues are typically about the sexual experience and its aftermath.

Even before the media’s focus on medication for erectile dysfunction, women frequently couched their most common sexual concerns—those of low sexual desire —in medical terms: “I know I have some kind of hormone imbalance,” or “I have had no desire since my tubal ligation, second pregnancy, hysterectomy, or menopause.” Access to the Internet aided these self-proposed etiologies. Women usually acknowledge that an unhappy relationship, emotional or physical abuse, drug or alcohol addiction, and depression would logically interfere with their sexual desire. However, when they perceive that none of this is relevant to them, they conclude their lack of desire must be something “medical” even if their physicians could not identify it. Recent promotion of unidentified but previously ignored biological causes of women’s sexual dysfunction continues to further fuel these beliefs. While studies continue to find robust correlation of women’s sexual desire with their mental health, self-image, and the quality of the interpersonal relationship, to date there is no clarity concerning biological factors. The singular exception is the sexual side effects of medications, chiefly the antidepressants. Even in the context of chronic disease such as renal failure, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, or breast cancer, mental and relationship health, along with degree of stress, remain the major factors determining women’s sexual desire.

Multiple Motivations for Sex Coexist: Emotional Intimacy Predominates

Women often recall desire early on in relationships when they were caught up in the excitement of the chase, idealized their partners, and had many motivations beyond fulfilling a seemingly innate sexual hunger. These motivations might have included enjoying feeling attractive and attracted; fulfilling an expectation; feeling better about herself; and wanting the relationship in order to feel loved or normal or to leave her family, further a career or distance herself from a church or a culture. The woman was oblivious of the interaction of these incentives, and it seemed easy to accept or instigate and enjoy sexual activity. Sex was novel, and there were many sexual triggers and settings. Sex was easy and seemed spontaneous. Provided the sexual outcome was rewarding, the wanting of shared sexual sensations and the mutual vulnerability increased. Perhaps the secrecy or uncertainty of the liaison, even its lack of societal approval, enhanced the stimuli. The growing emotional intimacy can lead some women even in early stages of a relationship to state that their main reason for engaging in sex is to feel closer to the partner.

Empirical data now confirm that when women explain why they agree to, or initiate, sex, they emphasize nurturing of the emotional intimacy. The aspirations to show that the partner is wanted, loved, missed, and appreciated; to give something to the partner; to show that an argument is over; and to increase the sense of bonding, commitment, trust, and confidence in the relationship become cemented by sexual experiences, assuming they are satisfying. Accessing sexual arousal becomes more clearly a deliberate choice. Empirical research involving 1,500 young women yielded 235 discrete motivations for sex.1 The researchers divided the reasons into four domains: love and intimacy, physical pleasure and stress relief, goal attainment, and mate guarding. The first domain was predominant. In similar content analysis research into the sexual motivation and desire literature, intimacy was the most frequently endorsed among 16 options. Multiple items were endorsed by the majority of 203 women in monogamous relationships.2 During a qualitative study of 34 women, when asked to define their goal or object of desire, 80% identified sharing emotional contact, whereas the goal of intercourse was far less frequent, as was the goal of orgasm.3 Triggers of desire/arousal included physical stimuli, as well as visual ones or triggers from the partner’s behavior or from their own memories. These studies confirm the clinical impression that initially, during any one sexual engagement, a woman may be sexually neutral but motivated by multiple incentives. My conclusion, in line with others,4,5 is that the presence sexual stimuli, the ability to attend to those stimuli, and a context that is conducive to physical intimacy are crucial elements of the sexual response. Any initial apparently “innate” or “spontaneous” desire/drive (possibly cyclical with menses) adds to this response at any or all points, as shown in Figure 5.1, but it is not an essential component, and for many sexually satisfied women, it is extremely rare (whereas for men it is often present).

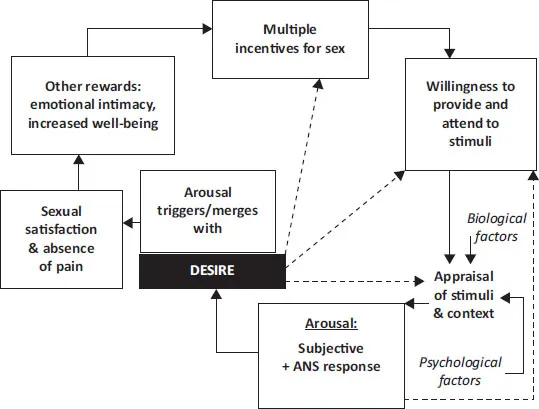

Figure 5.1 Circular incentives-based model of variable sexual responding that includes the stimuli needed for that responding and reflects the vital component of the mind’s appraisal of those stimuli to allow arousal and desire for more intense arousal, or, instead, to preclude any arousal response and any chance of triggering desire. Motivation is increased when the outcome is rewarding. A sense of desire may sometimes be present at the outset, adding to other sexual motivations and positively influencing the mind’s appraisal of sexual stimuli. ANS, autonomic nervous system.

Current Model of Sexual Response

Figure 5.1 is a model of variable sexual responding that includes the stimuli needed for that responding and reflects the vital component of the mind’s appraisal of those stimuli to allow arousal and desire for more of the same, or, instead, to preclude any arousal response and any chance of triggering desire. Women frequently confirm that these “circles within circles” reflect their experiences. Unlike the linear models of human sexual response of Masters and Johnson,6 Lief,7 and Kaplan8 with a predominantly genital focus, this incentive model reflects how arousal can precede and then accompany a responsive or developed form of desire.

The circular response may be cycled many times during one sexual encounter. Subtle erotic stimuli may be appraised to lead to low-key arousal, which then facilitates acceptance of more specifically sexual stimuli to then cause increased arousal. Women frequently initially need non-physical stimuli, then non-genital physical stimuli, then non-penetrative genital stimulation before vaginal penetration. Sometimes the experience of arousal is dysphoric—the woman’s appraisal of the sensations of arousal does not permit more intense arousal. Thus, she reports, “It’s all so fleeting.” Positive experiences provide reward to further motivation in the future, and negative experiences efficiently do the opposite.

Emotional Intimacy Is Vital but Not Sufficient

Psychological intimacy can breed a wanting of sexual intimacy. However, psychological intimacy—though vital—is insufficient. Useful sexual stimuli and appropriate context are necessary. Stimuli external to the woman often move her from sexual neutrality to arousal. Stimuli are both mental and physical, but the context may be more important than the stimuli themselves—for instance, visually explicit sexual stimuli out of context, although possibly causing a fairly prompt genital vasocongestive response of which the woman is relatively unaware, are typically not considered subjectively arousing. Women speak frequently of the need for caring, attractive behavior from their partner throughout the day, which will determine the effectiveness of later sexual stimuli. Empirical study has confirmed the importance of partner compatibility in determining sexual dysfunction and sexual distress.9 So the contextual factors include the interpersonal, societal, and environmental—for instance, private, safe, erotic, not too late at night.

When sexual stimuli and an appropriate context are missing, despite psychological intimacy, the woman’s feelings for her partner are typically those of affection, love, and caring. A woman often discusses her likely contentment if she and her partner could be just “soul mates” but adds that any contentment would be marred by guilt: “I know this sounds awful—but I wouldn’t care if we never have sex again.” There is sadness that this is not what society expects, and there is fear that the relationship will suffer. These feelings tend to counter-balance any positive thoughts of “no more sex.”

Is all Desire Responsive?

So what is the role of seemingly “spontaneous” desire? Some researchers hypothesize that desire is always responsive to something—even if the person is unaware of the sexual trigger.4,5 But traditionally the term spontaneous desire is usually meant to describe an innate sense of need of sexual tension and its release, preferably with someone else, which appears not be triggered by anything in the current environment or by deliberate focusing of the mind on sexual matters.

Sexual function is a complex blending of mind and body. Neurotransmitters and hormones permit sexual stimuli to register unconsciously and thereby alter the autonomic nervous system. This leads to increased genital blood flow. Simultaneously, but in a less prompt manner, the stimuli are consciously appraised as mentally sexually arousing/attractive, potentially triggering a responsive desire. The neurotransmitters and hormones permit this process, but there is no evidence that, in normal physiological amounts, these neurochemical agents actually generate a feeling of sexual desire.

This brings us to the difficulties with the traditional markers of women’s sexual desire, namely, sexual fantasies and thoughts about sex, as well as self-stimulation. Women tell of their use of fantasy in order to become aroused or in order to stop being distracted during the sexual experience.10 For them, the presence of fantasies is hardly a reflection of high innate spontaneous desire. The previously mentioned qualitative study of 34 women illustrates the lack of importance of fantasies for the participants: fantasies were recorded as present on the validated questionnaire, but as the women spoke about desire, fantasies did not feature at all.3 Empirical research indicates that motivation for partnered sexual activity may be distinct from solitary sexual desire as evidenced by sexual thoughts and fantasies, and that motivation for partnered sex is far more relevant to sexual well-being. Of 65 men and 65 women reporting close to absent interest in partnered sexual activity, some 75% continued to report sexual thoughts—some three or more times per month for women.11 Other research has identified a marked discrepancy between a person’s self-diagnosis and a clinician’s diagnosis of low desire, the latter focusing on the traditional markers of sexual thoughts and fantasies.12

Both small and large studies confirm that the absence of a sense of ongoing desire does not preclude a sexually satisfactory life. The data from the Study of Women Across the Nation (SWAN) showed that the majority of 3,250 multiethnic middle-aged women in North America confirmed satisfaction with their physical and sexual pleasure but documented a zero or infrequent sense of sexual desire.13

Of 1,865 women reporting healthy sexual function with easy sexual arousal, close to one-third rarely or never began a sexual experience with a sense of sexual desire; it was reliably accessed once they were aroused.14 Only 15% of women in the group limited sexual activity to times they felt desire at the outset. Empirical support for the concept that arousal may precede desire and then the two coexist is now strong and includes data from older and younger women.4,14,15,16 The definition of Sexual Interest Arousal Disorder (SIAD), in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), merges women’s sexual interest (motivation) with arousal and focuses away from initial/anticipatory desire.17 Unfortunately, validated questionnaires that are currently available for use to assess sexual function are based on models of sexual response in which desire is assumed to be necessary at the outset of the engagement—a serious limitation to research.18 Thus, it is to be expected that women reporting more responsive desire than seemin...