![]()

![]()

Preface

“To be truly radical is to make hope possible, rather than despair convincing.”

Raymond Williams

We are entering a time of change, a time when many tipping points will be passed, resulting in unexpected consequences for our way of life. Yet it is a time of great opportunity, a time when it is possible to open up a thriving, if different, future.

This book is a hopeful response to the sense of doom that pervades so much of the sustainability discourse and the feelings of hopelessness and powerlessness that come with facing challenges that seem insurmountable. As individuals we have followed a journey familiar to many sustainability advocates and practitioners – alternating between optimism, cynicism and outright despondency, yet always searching for a message of hope, a future vision of a flourishing world. Dealing on a daily basis with the increasingly dire predictions of science about climate change, ecosystem service degradation, and the eventual fallout for human society, is depressing and emotionally exhausting. As teachers we are also confronted with the difficult task of instilling an awareness of humankind’s negative impacts and a sense of urgency about the need for change, while countering this distressing message with a positive view.

The great responsibility that comes with teaching this message was brought home by the suicide of a student who could not face the overwhelmingly negative vision of the future that is so much part of the sustainability narrative. This tragic event provided the impetus for this book. We needed to find hope, not just for the sake of the next generation, but also as redemption for our part in creating this mess.

For many years, as we met on the conference circuit, we have been talking about developing a more positive vision of the future, about mapping a regenerative development path rooted not in fear and scarcity, but in love and abundance. In the process we have met many others who were struggling with the same question: finding a path that would go beyond the irrationality of attempting to reduce consumption while providing more goods and services to an ever-growing, ever-wealthier and ever more materialistic global population. This book is a tribute to all those positivity pioneers, and to put it together we relied greatly on this international network of what Pamela Mang terms the regenerates. We interviewed more than fifty people in the United States, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Their enthusiastic support inspired and encouraged us every step of the way.

The result is a book that is meant to provide not just hope, but also inspiration to all kinds of designers, whether they are designing spaces and places, systems and processes, or simply new ways of being in the world. It is not a technical ‘how to’ book. In it you will not find instructions on installing systems or choosing materials or planting gardens. Instead, we want to show the reader what is possible when we come to the design problem with a different mindset, a different vision, a different worldview.

We firmly believe that there is hope; that we can choose to contribute to the creation of a thriving and abundant world. And we are not alone. There has been a subtle but marked shift in the global conversation, a shift from negative to positive, from despair to hope. Going beyond the language of mere sustainability, words such as abundant, thriving, and flourishing are being bandied about. We are striving not just for modest resilience, but for the superpower of anti-fragility.

This is no Pollyanna optimism, but a sober understanding that change is necessary, if uncomfortable; that out of adversity comes strength; and that we do have a role to play in what can only be described as a global healing. As Maddy Harland and William Keepin propose in The Song of the Earth1:

We are called to serve in two distinct capacities: as hospice workers to a dying civilization, and as midwives to an emerging civilization. We are called to move through the world with open hearts – being present to the grief and decay of a waning civilization – while at the same time maintaining heartfelt enthusiasm as we focus our energies on visionary inspiration and building unprecedented new forms of human community that will serve the future evolution of humanity.

We have everything we need to contribute to such an emerging civilization, we only need to open our hearts. For the key is love. Not passionate Eros or virtuous Agape, but Philia – love expressed through affinity. We need to rediscover and embrace the affinity we have with all the communities of life to which we belong. This book argues that vital to this is an active, contributive engagement with the world. To illustrate what this means, we use case studies from the built environment to answer questions such as: ‘How can projects focus on creating a positive ecological footprint and contribute to community?’; ‘How can we as practitioners restore and enrich the relationships embodied in our projects?’; and ‘How does design focus hope and create a positive legacy?’ We hope that the stories we tell will show how others are doing it, and inspire you to find your own way of contributing to the creation of a thriving future.

ENDNOTE

1 Harland, M. and Keepin, W. (2012). The Song of the Earth: A Synthesis of the Scientific and Spiritual Worldviews. East Meon, Hampshire, UK: Permanent Publications.

![]()

Chapter 1

Why do we need regenerative sustainability?

“It’s the end of the world as we know it, and I feel fine”

REM, 1987

The world as we know it is coming to an end. Some would say this is not necessarily a bad thing. As the world hurtles headlong towards what Paul Gilding, with great understatement, calls the Great Disruption, there is a growing movement intent on not wasting a good crisis and the opportunities for renewal it brings. These are the thinkers and designers who believe that current approaches to sustainable building are merely rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic; that to create a future in which humans will thrive, and not just survive the calamities we have created, a different approach is necessary. Whether they call such an approach regenerative design or Positive Development or biophilic design, it is based on one common idea: transforming the way we create the built environment so that it contributes to the well-being, nourishment and regeneration of the world and all its communities. With this book we explore the various practices being developed to go beyond contemporary notions of sustainability and green design to create a world in which humans and their ecosystems can flourish.

Redefining ‘the problem’

If we allow ourselves an honest look, the future looks very scary. The operating parameters of our environment are changing in unpredictable and unprecedented ways. If we are lucky, these changes will be relatively slow and linear and we shall have time to adapt. However, the odds are against this. By now we are well aware that the tenancy of humans on Planet Earth is rapidly pushing the planet past certain limits. The world has already exceeded a number of critical operating boundaries in the ecosystem services provided to humanity (and other living beings) and is falling short of meeting important quality of life indicators.1 In 2005 the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment released the results of a four-year global study into the state of global ecosystem services and the possible consequences of anticipated ecosystem change on human well-being. The assessment found that nearly two-thirds of the essential services provided by nature to humankind are in decline worldwide, and in many cases we are literally living on borrowed time. The scientists concluded that the protection of these services can no longer be seen as an optional extra, to be considered once more ‘pressing’ concerns, such as human development and wealth creation, have been dealt with. They end with the warning that “the results of human activity are putting such a strain on the natural functions of Earth that the ability of the planet’s ecosystems to sustain future generations can no longer be taken for granted”.2

A 2009 study3 identified nine planetary systems boundaries that should not be crossed if the planet is to continue providing a safe operating space for humans. Three of these boundaries (biodiversity, the nitrogen cycle and climate regulation) have already been crossed, despite many early warnings by scientists. Consider this: as early as 1896, Svante Arrhenius4 warned that the Industrial Revolution’s carbon dioxide emissions may eventually result in global warming and climate change. After four Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Assessment Reports and 17 Convention of Parties meetings, this warning has moved from the realm of the possible, through that of the probable, and finally to certainty. What was the international response to this? Instead of reducing global greenhouse gas emissions, global emission rates continue to increase at a growing rate and so do temperatures. Average global surface temperatures were 0.8°C warmer during the first decade of the 21st century than during the first decade of the 20th century. If emissions continue to grow, it is highly probable that large regions of the planet will exceed a 2°C increase in average annual temperatures by 2040,5 with devastating consequences not just for the global economy, but for all life on the planet.

It is easy to get caught up in the distress caused by these changes and the threats they pose to current human systems. There will certainly be many painful and heartbreaking transitions and system collapses. But there is also a wonderful opportunity in this period of change to create an alternative model of development that will lead to a thriving future. However, to harness this opportunity we need to think differently about how we see the world, how we define the problems to be solved, and how we can contribute as designers.

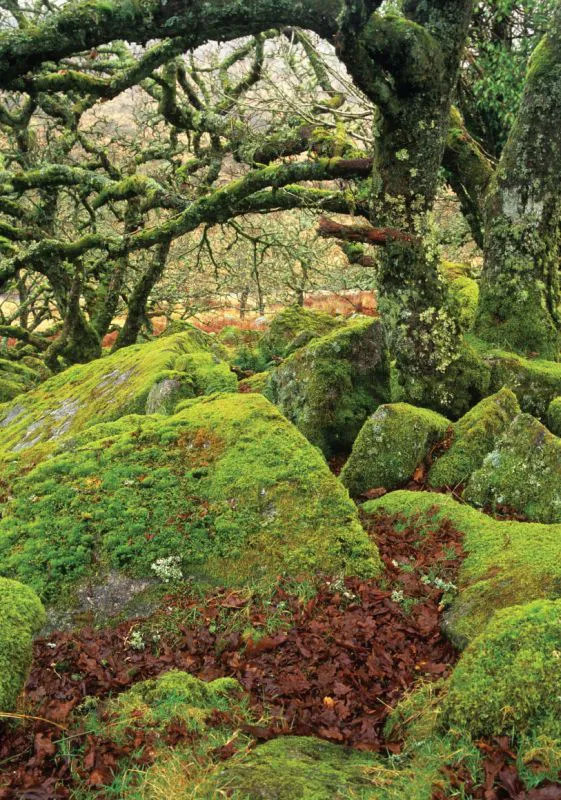

PHOTO: C DU PLESSIS

The first step is to move away from present fear-based narratives. Currently, the predominant narrative of sustainability is that of scarcity, negative impacts and disruptive change in the face of growing socioeconomic needs. The subtext is that of uncertainty and sacrifice, which in turn engenders resistance to change. We see this thinking clearly in the international discourse on climate change. As the planet is already experiencing the effects of global warming, scientists are pushing for lower ‘safe limits’ of emissions and atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, while governments, intent on rescuing a flailing world economy, argue for increasing these limits to politically acceptable levels. Thus we see that, despite the many published warnings of scientists and professional risk analysts about the probable perils of overshooting planetary boundaries and the dire social and economic consequences of such overshoot, the majority of humans are still trapped in denial, and in the case of the developing countries, also anger at losing out. To move forward it is necessary to develop a narrative of positive impacts leading to an abundant and flourishing world.

PHOTO: C DU PLESSIS

Central to this book is the idea that the problems of climate change, biodiversity loss and dysfunctional ecosystem services are not the real problem, but merely the symptoms. The real problem lies in the stories we tell ourselves to justify why we dither and procrastinate, and those we tell about sustainability and how strongly they are still being influenced by the worldviews and value systems that created the problem.

Central to this book is the idea that the problems of climate change, biodiversity loss and dysfunctional ecosystem services are not the real problem, but merely the symptoms.

The stories we tell each other

There are two stories we use to avoid accepting both the scientific evidence for the need for change and the ethos required to change our behaviour and aspirations and take action. The first is the story that we cannot change the system, that we cannot fight the enormous systemic inertia of what has become a global system of interdependent economies and increasingly shared consumerist value systems driven as much by philanthropy as by the media. The second story is that there is no c...