Evolutionary psychology is different: Proximate and ultimate explanations

Psychology is the science of human behavior, and as such it has proposed many useful theories as to why humans behave the way they do. One current theory of the psychological disorder schizophrenia, for example, is that it is the result of an excess or heightened sensitivity to the neurotransmitter dopamine (Kring, Johnson, Davison & Neale, 2014; see Chapter 8); explanations for prejudice center around in-group–out-group bias distinctions (see Chapter 5); whereas repeated failed relationships have been explained by the development of different attachment styles in infancy (Chisholm, 1999; see Chapter 6). Although all of these explanations are very different from one another (the first is biological, the second social, the third developmental), they are all similar in that they are proximate explanations. They take a particular phenomenon and ask what current or past factors led to that particular behavior. In contrast, evolutionary psychology asks for ultimate explanations to questions: it asks what are the particular evolutionary processes that led to a person exhibiting that particular behavior?

Key Terms

Proximate explanation In psychology and biology, an explanation for a behavior couched in terms of current biological, cognitive, social or developmental mechanisms.

Ultimate explanation An explanation that attempts to explain why a particular behavior evolved in the first place.

To illustrate the difference, consider the emotion of disgust. This seems to be a cultural universal (it occurs in all cultures that have been studied; Brown, 1991), and there have been quite a few attempts to study it. Some researchers have studied the kinds of things that promote the disgust response, others have studied the neurological causes of disgust and still others have investigated the way that disgust develops through childhood (Haidt, McCauley & Rozin, 1994). But an evolutionary psychologist would ask a different question: what is disgust for? Or, put another way, what is the evolutionary benefit to the individual of having a disgust response (we will discuss who the beneficiaries of a particular behavior are later in this chapter).

One answer to this question is that disgust is a solution to a problem called the “omnivores dilemma.” Unlike many other species (cows and giant pandas spring to mind), humans are capable of eating a range of very different foods: meat, fruit and vegetables of course, but also grubs, insects, eyeballs and intestines–all of which are perfectly nutritious and, in some cultures, considered a delicacy. But amidst all of the good things to eat are things that are inedible (hair, grass), poisonous (the livers of certain animals, many plants and fungi) or, more importantly, contain pathogens such as bacteria (rotten meat, feces). So how do omnivores such as humans solve this problem? One solution is to consume anything in infancy. Toddlers regularly eat worms, soil and, in some cases, the contents of their own diapers, perhaps relying on their parents to prevent them from eating anything too dangerous. But from about 3 or 4 years of age, a child’s dietary repertoire becomes increasingly fixed, favoring things that they are used to and avoiding novel foods (referred to as neophobia), and many novel foods are seen as disgusting. So, disgust prevents contamination from potentially dangerous materials. It is an extremely aversive emotion, first encouraging individuals to withdraw from the object, and–should it enter the mouth–promoting the gag response, the purpose of which is to expel the offending item from the body. For those readers who are unclear as to what this process involves, watch an episode of I’m a Celebrity … Get Me Out of Here! Disgust has, of course, subsequently become expanded to take on a moral dimension (think of incest or child abuse).

Discuss and Debate–Neophobia

Think of times when you have been exposed to new foods and what you initially made of them. Did you immediately like them? Did you consider them repulsive? Did you eventually overcome your revulsion? If so, how, and why? Peer pressure and the desire to impress other people is often a motivation (say, to impress your peers or a member of the opposite sex). But neophobia can have remarkably deep roots–something that makes entertaining television when junk-food junkies are asked to swap to a healthy diet.

So we can see here a potential answer to the ultimate question as to what disgust is for. It is an evolved mechanism to prevent us from putting the wrong kind of thing in our mouths, which, as omnivores, is a potentially very large set of things indeed. As an aside, we might apply this line of thinking to pleasant and unpleasant sensations. Why do some things feel, taste, smell, look or sound good and some things the opposite? There is nothing about feces which makes it intrinsically bad smelling; rather, the aversive smell is the result of the above adaptation: it smells bad so that we avoid it. Doubtless to a dung beetle, nothing else smells so sweet.

Discuss and Debate–Proximate and Ultimate Explanations

As an exercise, try thinking of some psychological topics and consider proximate and ultimate questions that might be asked of them. To get you started, here are a few examples: out-group prejudice, laughter, schizophrenia and forgetting.

Where ultimate explanations come from: Evolution by natural selection

Ultimate explanations only make sense because evolution has a well-worked-out theory: natural selection. Before discussing this, it is useful to spend a few words discussing what a theory actually is. The purpose of a theory is to explain things in the world, and some theories–and the theory of evolution by natural selection is certainly one of them–are supported by a great deal of evidence. So, if you are thinking that theory necessarily entails some kind of vague guess, it does not. As we shall see, evolution by natural selection is precise and is supported by mountains of scientific evidence. So much evidence, in fact, that were it to be proved to be untrue, scientists would be almost as surprised as if they were to find out that sun is not the center of the solar system.

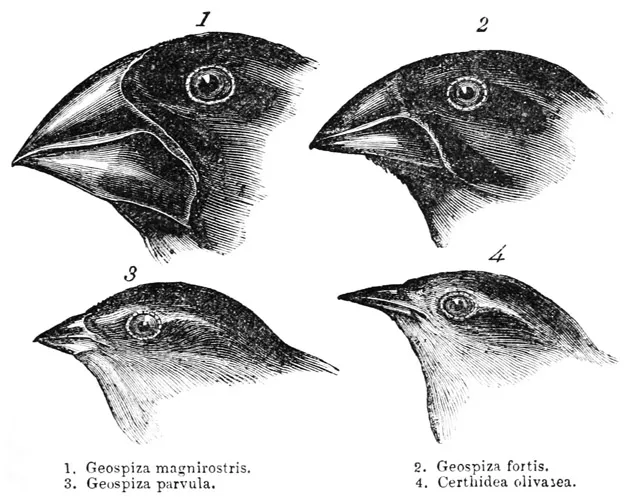

Figure 1.1 Darwin’s finches, by John Gould.

Natural selection was Darwin’s theory. Although Darwin’s contemporary, Alfred Russell Wallace, had a very similar idea, it was Darwin who managed to get the theory published first in 1859’s On the Origin of Species. During his famous circumnavigation of the world on board the HMS Beagle between 1831 and 1836, Darwin noticed both the great diversity of life and the fact that members of each species seemed to fit their environments so well. It was as if each organism had been designed to deal with the challenges of its particular environment. Figure 1.1 shows what have come to be known as Darwin’s finches that live on the Galápagos Islands, famously visited by Darwin during his voyage. The birds’ bills are well designed to exploit their particular ecological niche (and in particular to solve the foraging challenges of each Island). Before you read on, can you guess what each of the four birds eat?

Key Term

Ecological niche A term used for the way of life of a particular organism–for example, the foodstuffs it consumes or the habitat it lives in.

The answers are that (1) primarily eats nuts, (2) eats grain and (3) and (4) both eat insects. And the bill design reflects this, depending on whether they need a nutcracker, a grain crusher or a more delicate instrument for persuading insects out of their holes. As well as partly inspiring Darwin to produce his theory of evolution, changes in their physical structure as the habitat of each Island has changed since Darwin’s death has provided evidence for evolution in action.

Darwin’s theory

On his return to England, Darwin spent many years formulating how this fit with the environment had come about. Many people prior to Darwin had attempted to solve the same puzzle and produced various solutions. The philosopher William Paley concluded that complex design, such as that found in living organisms, could only be explained by their being produced by divine creator (Paley, 1802). Although notionally a Christian, Darwin rejected this approach as unscientific: science should explain phenomena in terms of natural rather than supernatural processes. Darwin’s task was to explain how design could come about without there being a designer.

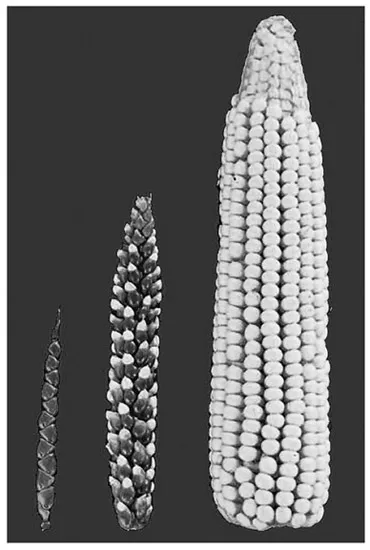

He called the process that he discovered natural selection. The name comes by analogy with artificial selection, which is where plants or animals can be changed over time by humans selectively cross-breeding them for desired traits (see Figure 1.2). Natural selection involves no designer, and it is as stunning in its simplicity as it is far-reaching in its implications. It hangs on three principles.

The first is heritability. Offspring tend to resemble their parents more than they do other members of the species. Something is clearly passed from parent to offspring that causes this similarity. Now we call this something genes, but Darwin knew nothing about genetics at the time.

The second is variation. Although parents tend to resemble their offspring, they differ in subtle but sometimes important ways. There are a number of sources of variation. Mutations are the simplest. We now know that genes play crucial role in determining an individual’s makeup, and we know that genes are made of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA; see Chapter 2). DNA is a large and very complex chemical, and as such its structure can be changed by things such as radiation or the presence of other chemicals. Nuclear accidents such as that which occurred at the Chernobyl nuclear power station in 1986 have led to an increase in genetic abnormalities and birth defects as a result of mutations caused by radiation. But, radiation is present at low concentrations everywhere, all the time, which can cause changes in the genetic material of offspring, causing them to be subtly different from their parents.

Figure 1.2 Sweet corn has been artificially selected for its sweetness, size and color. The cob on the left is the original wild version, the one in the middle is after a degree of cross-breeding and the one on the right is the current form.

In addition to mutations, another source of variation is sex. Bacteria make copies of themselves, but humans and many other organisms do not. Instead they combine the genes from two individuals to produce a unique combination in the offspring (see Chapter 2).

The third principle is differential reproductive success, which is a bit of a mouthful, but is in many ways Darwin’s most important insight. As we have seen, offspring are different from their parents, and this can have an effect on the organism’s ability to survive and reproduce. In many (probably most) cases these differences have either no effect or–as we see with birth abnormalities–reduce survival and reproduction chances, but in some cases the offspring can be better at surviving and/or reproducing than their parents are. And, of course, they will tend to pass these on to their offspring (heritability again), and in the long run the new form may well replace the old form.

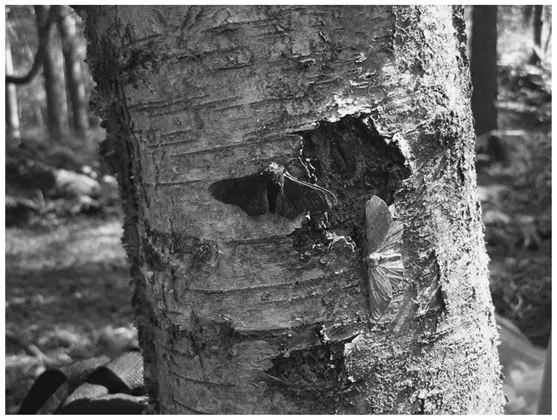

Figure 1.3 The peppered moth in speckled (peppered) and dark forms.

The textbook example of this is the peppered moth (Biston betularia). As its name implies, this moth traditionally has a “peppered” or speckled coloration, all the better for hiding on the lichen that clings to the bark of the trees in the forests, which are the moth’s main habitat. Lichens are plant-like organisms that are, in fact, a partnership between a...