![]()

CHAPTER

1 | GEOGRAPHY AND CREATIVITY

Making Connections |

Stephen Scoffham

This chapter explores what we mean by creativity. It begins by considering some of the different definitions and features of creative thought and how these might relate to classroom practice. It is suggested that creative learning experiences have the potential to enrich the curriculum and enhance personal well-being. The rich possibilities that are offered by geography are outlined. The chapter concludes by arguing that creative approaches involving joyful and imaginative learning set in a values context, will build children’s capacities in the face of an increasingly uncertain future.

INTRODUCTION

Creativity is an elusive concept. It is treasured by many educationalists as one of the key elements of effective teaching, yet remains ill-defined and poorly understood. Historically, creativity was associated with the act of creation, which was seen as a divine gift. The notion that the world was created by God is a central tenet in many religious texts. We learn from the Bible, for example, how, in the beginning, God created the heavens and Earth, progressively adding light, water, sky and living things. Certainly, there are good reasons why people in the past might have wanted to invoke superhuman powers to explain the magic and beauty of life in all its diversity. How else could these wonders have come about? Interestingly, the association between creation and creativity is embedded in our language. Both terms are derived from the same Latin verb creare, which means to produce or to make. It is no coincidence that the word ‘creature’ also shares the same linguistic root. Small wonder then that we sometimes feel uncomfortable when we are invited to be creative. The student who, when asked to note her responses to a heritage site, roundly declared ‘I don’t do creativity!’ was reflecting this unease. Her fear was that she would be unable to come up with something that required exceptional talents or gifts.

In modern times the meaning of creativity has shifted considerably. While the idea that creativity implies a special gift still informs popular usage, it has also taken on a more prosaic dimension. Solving the problems that make up our everyday lives has come to be seen as a creative activity. As we think of solutions, suggest alternatives and imagine what might happen in the future, we are drawing on our creative powers. In education, especially, creativity has come to be associated with thinking and learning. Scoffham and Barnes (2007: 13), for example, argue that creativity is a ‘fundamental aspect of human thought’. This means that, rather than being restricted to the expressive arts, creativity has relevance for all curriculum areas.

The overlap between creativity and human thought places it at the centre of the educational agenda. Moreover, there is an increasing realisation that creativity is not fixed. Some years ago, a key UK government report, All Our Futures (NACCCE 1999: 28), made the point that ‘all people are capable of creative achievement in some area of activity’. It now seems that we can develop our creative capacities whatever area we are involved in. Drawing on research, Lucas and Claxton (2011) argue that our mental attitude and temperament are not set in stone but are capable of change. Not only do they offer compelling evidence to support this claim, but they also outline practical strategies for effecting change. This is encouraging news because teachers are in a prime position to construct situations in which creativity is likely to flourish.

DEFINITIONS OF CREATIVITY

There are many definitions of creativity. In educational circles the definition that was put forward by the National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education (NACCCE 1999) has gained considerable currency and informed much subsequent thinking. The committee argued that creativity always involves the four following characteristics:

(a) thinking and behaving imaginatively;

(b) purposeful activity directed towards an objective;

(c) processes that generate something which is original;

(d) outcomes that are of value in relation to the objective.

This led the NACCCE to define creativity as ‘imaginative activity fashioned so as to produce outcomes that are both original and of value’ (ibid.: 30).

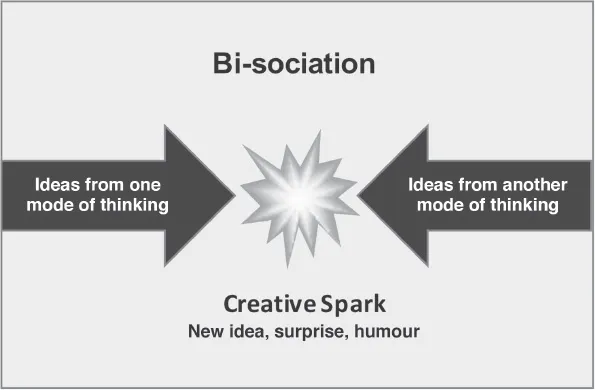

The NACCCE definition places considerable stress on products and outcomes and underplays the role of experimentation and flexibility. Sometimes we simply do not know where our thoughts are heading. Craft (2000) draws attention to this aspect of creativity in what she calls ‘possibility thinking’. This involves both solving problems and raising questions. She also reminds us that creativity is not a single process but involves multiple dimensions that include looking into ourselves as well as outwards towards our surroundings. De Bono (2010), who coined the term ‘lateral thinking’, takes a different approach when he highlights the importance of making connections and seeking alternatives. He stresses how creativity involves going beyond the obvious to generate novel solutions. One of de Bono’s particular interests is to develop strategies that allow people to pool their thoughts. His ‘thinking hats’ is a neat device for avoiding the limiting effect of binary approaches. Another enduring insight comes from Koestler (1964), who emphasises the link between creativity, surprise and humour. The way that two ideas, often from different subjects or discipline areas, can come together to generate a creative spark underpins his notion of bi-sociation (Figure 1.1).

There is increasing recognition that creativity needs to be viewed in a cultural context. Western interpretations tend to emphasise the role of the individual and are orientated towards products and innovation. Eastern perspectives are more likely to focus on team and group endeavour. They may also emphasise personal fulfilment, the expression of inner truths and a sense of oneness with the world. Hinduism, for example, interprets creativity in spiritual or religious terms and sees time and history as cyclical. In education, where many teachers will be working with pupils from multicultural backgrounds, the dangers of adopting a one-size-fits-all approach to creativity will be immediately apparent.

Figure 1.1 When ideas from two different modes or lines of thinking interact it generates humour, surprise and creative sparks

Source: after Koestler (1964)

To conclude, it is perhaps best to think of creativity as having a number of different dimensions ranging from the cognitive to the social and emotional. Choosing to focus on one aspect of creativity may lead us to neglect the others. However, it is generally accepted across cultures that creativity is a positive concept. There is also significant agreement that creativity is strongly associated with play, imagination and the emotions, and that it leads to new ways of seeing and thinking. These ideas are explored further in the following section.

Play

Young children are well known for their curiosity and their desire for play. They have a seemingly insatiable interest in the world around them and are constantly asking questions that adults find alternatively charming and annoying. Their questions appear charming because they often suggest unusual or unexpected connections. They are annoying partly because children ask them so persistently and partly because we often don’t know the answers ourselves; or if we do, we find it hard to express them in terms children can understand.

One of the great qualities of play is that it is experimental, flexible and entertaining. Katz (2004) declares that play is about making and remaking the world. Young children are particularly good at this. Schools and teachers are sometimes accused of undermining children’s natural capacity for inventiveness, but this is perhaps unfair. As children become older they come to recognise how ideas can fit together in useful patterns and networks. In other words, experience teaches them how best to approach different situations, and their capacity for unusual or divergent thought is reduced in consequence.

Generating ideas

Creativity is also strongly associated with generating new ideas. Some people, such as famous musicians, artists, scientists and mathematicians, have been so successful at devising new ideas that they have changed the way we see the world. This is sometimes termed ‘big C’ creativity, and it is, by definition, a comparatively rare phenomenon. By contrast, the kind of creativity we are likely to engage in on an everyday basis is known as ‘small C’ creativity. Both ‘big C’ and ‘small C’ creativity are about being original, even if the scale and impact are vastly different. It is also important to note that coming up with new ideas can be a highly stimulating and rewarding process. In his review of the primary school curriculum, Alexander (2010: 213) reports that children ‘valued those subjects that sparked their curiosity and encouraged them to explore’. We are all attracted by novelty, and the complaint that something is boring usually arises because it is repetitive and lacks challenge. Developing new ways of thinking is stimulating even if it may also be unsettling.

Imagination

Using imagination is another aspect of creativity. This can take make different forms. It may involve asking unusual questions, envisaging alternatives or re-examining something that is taken for granted and seeing it in a different light. Coming up with new ideas can be fun, but unless these ideas are applied in some way they remain in the world of fantasy. The problem is that it is not always clear at the time whether a new idea is useful or not. Thus divergent thinking can oscillate between appearing highly creative on the one hand and whacky and weird on the other. Perhaps this is why genius and madness are often associated in the popular imagination. There are times when the boundary between the two is surprisingly thin.

Emotions

Creativity is not purely intellectual activity. Harnessing our emotional energies is an essential part of creativity and it involves accessing layers of thought that lie beneath the surface of everyday cognition. Drawing on evidence from neuroscience, Immordino-Yang and Damasio (2007) argue that while creativity may be informed by high reason, it is fundamentally based on a platform of emotional thought in both social and non-social contexts. They go on to argue that motivation – the dynamo that drives our learning – derives from emotional rather than cognitive neural networks. Craft (2000) makes a similar point when she declares that the sources of creativity are not always conscious or rational. She reminds us that ‘the intuitive, spiritual and emotional also feed creativity’ and that these are themselves ‘fed by the bedrock of impulse’ (ibid.: 31).

Intuition

There is a sense in which creativity involves a particular type of thought. It involves making links and connections, allowing ideas to emerge and being open to suggestion. Lucas and Claxton (2011) draw on a metaphor used by neuroscientists to suggest that we can view mental processes as a landscape that can be made either steeper or flatter according to our state of mind. Definite modes of thinking correspond to a steep, mountainous landscape while more playful and dreamy modes relate to a gentler, flatter terrain. There are times when we need focused thinking that channels our thinking down deep valleys, but the flatter terrain is better at handling ambiguities. As Lucas and Claxton explain, ‘because the land is flat, neural patterns are much more able to bleed into one another, so you can find connections which are less stereotyped or conventional’ (ibid.: 75). It is also important to be able to switch between different modes so as to get the benefit of both. People who are less creative tend to be stuck in one mode. Being flexible and receptive to new ideas is part of a creative mindset.

CREATIVITY IN PRACTICE

So what does creativity look like in a classroom context? One distinction that has proved useful is the difference between (a) teaching creatively and (b) teaching for creativity.

Teaching creatively focuses attention on the teacher; it involves teachers drawing on their own skills and abilities to make learning more stimulating. Self-image is important here. Research shows that when teachers regard themselves as creative it can enhance their practice (Cremin et al. 2009). Confidence is important too. Working alongside other colleagues or with non-teacher practitioners such as artists, musicians, engineers and town planners is often an affirmative experience that can release latent talents. Your own enthusiasm, curiosity and desire to learn are liable to be much more important than being theatrical or showy.

Teaching for creativity, by contrast, directs attention to the learner and the quality of their experience. A focus on creativity is likely to involve giving pupils greater control over their learning. It may also favour collaborative and co-operative approaches in which children spark ideas off each other. Providing different entry points, encouraging pupils to ask questions and getting them to make connections are key strategies. Research suggests that a combination of teaching methods is likely to be more effective than any single approach. In their ...