eBook - ePub

Relativism

About this book

The issue of relativism looms large in many contemporary discussions of knowledge, reality, society, religion, culture and gender. Is truth relative? To what extent is knowledge dependent on context? Are there different logics? Do different cultures and societies see the world differently? And is reality itself something that is constructed? This book offers a path through these debates. O'Grady begins by clarifying what exactly relativism is and how it differs from scepticism and pluralism. He then examines five main types of cognitive relativism: alethic relativism, logical relativism, ontological relativism; epistemological relativism, and relativism about rationality. Each is clearly distinguised and the arguments for and against each are assessed. O'Grady offers a welcome survey of recent debates, engaging with the work of Davidson, Devitt, Kuhn, Putnam, Quine, Rorty, Searle, Winch and Wittgenstein, among others, and he offers a distinct position of his own on this hotly contested issue.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Relativism by Paul O'Grady in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy History & Theory1 Introduction to relativism

Relativism in contemporary thought

Looking back a century, one can see a striking degree of homogeneity among the philosophers of the early twentieth century in terms of the topics central to their concerns. More striking still is the apparent obscurity and abstruseness of those concerns, which seem at first glance to be far removed from the great debates of previous centuries, between realists and idealists, say, or rationalists and empiricists.

The German philosopher Gottlob Frege (1848–1925) devoted his career to the foundations of mathematics and was rewarded with profound indifference from his fellow philosophers and mathematicians. The English philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) devoted his early work to exactly the same issue, culminating in Principia Mathematica, which was such an intellectual effort, he said, that it rendered him incapable of ever producing such detailed work again. In his early work the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) focused even more narrowly on a critique of the work of Frege and Russell on the meaning of the logical constants. He also became aware of how much could be gained from such minute examination, saying that his work had widened out from the foundations of logic to the nature of the world. The Austrian philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) also started with the philosophy of geometry, before developing the phenomenological method, which was geared toward answering questions emerging from his earlier work. On the other side of the Atlantic, C. S. Peirce (1839–1914), the founder of American pragmatism, had been concerned with the nature of language and how it related to thought. From this he developed his theory of semiotics as a method for philosophy.

From these initial concerns came some of the great themes of twentieth-century philosophy. How exactly does language relate to thought? Can there be complex, conceptual thought without language? Are there irredeemable problems about putative private thought? These issues are captured under the general label the “Linguistic Turn”. The subsequent development of those early-twentieth-century positions has led to a bewildering heterogeneity in philosophy in the early twenty-first century. The very nature of philosophy is itself radically disputed: “analytic”, “continental”, “postmodern”, “critical theory”, “feminist” and “non-Western” are all prefixes that give a different meaning when joined to “philosophy”. The variety of thriving different schools, the number of professional philosophers, the proliferation of publications, the development of technology in helping research (word-processing, databases, the Internet, and so on) all manifest a radically different situation to that of one hundred years ago.

Nevertheless, in the midst of all this bustling diversity one can detect some common themes, one of which derives directly from the Linguistic Turn. The move to making language the centre of philosophical concern meant taking into account the social context in which language is produced. A unifying characteristic of much late-twentieth-century philosophy is attention to the social nature of thought, and so to the social dimension to our theories about reality. One might say that the Social Turn is as defining a characteristic of contemporary philosophy as the Linguistic Turn had been of the earlier period. Consider a representative list of some of the most prominent contemporary philosophers: Brandom, Davidson, Derrida, Habermas, McDowell, Putnam, Rorty. They all explicitly refer to societal forces operating on our thinking and attempt to draw out the implications for questions about meaning, ontology, truth and knowledge. Needless to say, they have quite different takes on what those implications are.

One such implication, which many have drawn, is that truth, meaning, ontology and knowledge are no longer best regarded as stable, unified concepts. In so far as there are many different societies, many different points of view, there is no single defining view that fixes the truth about any of these issues. Attempts to do so are often branded as cultural or intellectual imperialism – typically the imperialism of western middle-class men. Those who endorse such a critique typically view philosophy itself as inextricably tied up with these imperialistic tendencies and strike out in a new direction, eschewing philosophy in favour of critical theory, postmodernism, feminism, gender theory or whatever. This is not to say that those areas are necessarily outside philosophy, but that the more radical proponents of them want to move beyond contemporary philosophy.

Those remaining, however uneasily, within what can be regarded as academic philosophy are more worried about the diversity of approaches, and this is where the issue of relativism arises quite sharply. Relativism is nearly universally regarded as a bogeyman. Hardly any philosopher wants to be called a relativist; nearly everyone is against it – whatever it is. Even those who are regarded by their fellow philosophers as archetypal relativists vigorously deny that they are relativists and indeed launch strong attacks on what they see as relativism. So Rorty says, “‘Relativism’ is the view that every belief on a certain topic, or perhaps about any topic, is as good as every other. No one holds this view” (1982: 166). Putnam says, “That (total) relativism is inconsistent is a truism among philosophers ... The plethora of relativistic doctrines being marketed today (and marketed by highly intelligent thinkers) indicated [that] simple refutation will not suffice” (1981: 119). Yet when Michael Devitt argues against relativism in his book Realism and Truth he says, “Putnam’s position is reminiscent of the relativistic Kantianism I attributed to Kuhn, Feyerabend and the radical philosophers of science” (1997: 230). In his chapter on Rorty he says, “There are certainly plenty of signs of epistemic relativism in Rorty” (1997: 205). And this assessment could be repeated again and again among contemporary philosophers who regard Rorty and Putnam as being paradigmatically relativistic thinkers.

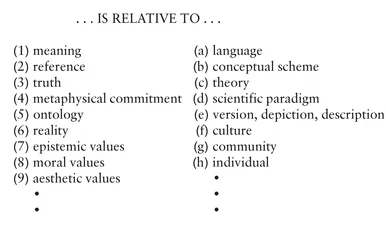

Whatever else one might take from the quotations just given, it is clear that “relativism” means a multitude of different things and that adding the title to any position usually means inviting a barrage of criticism from even those who are supposed to be on your side. In a recent discussion of the topic, Susan Haack sets up a bewildering variety of “relativisms” (1998: 149). She suggests that one could build up an identikit picture of the family using the following schema: Not every item on the left could fit with every one on the right and vice versa but, among the ones that can be linked, the sense of a large, loosely connected family begins to emerge. This illustrates starkly a grave problem with discussions of “relativism”: the multiplicity of positions covered by the term. Attacks on it, and indeed defences of it, usually confuse a variety of importantly different positions under a single label.

So what do I mean by “relativism”? I’ll begin by jettisoning some issues. I will not deal with moral relativism. This is the view that there are no universal moral norms – that morality is local or culturally relative or some other non-universal view. A great deal of literature exists on this, but I shall pass over it simply because it is not the focus of this book. The kind of relativism I’m interested in exploring could perhaps be called “cognitive relativism”. A simple way of characterizing this is that it is all the relativism that’s left when you leave out moral and aesthetic relativism. It covers issues in epistemology, metaphysics, philosophy of language and philosophy of logic, among others. However, in leaving aside moral relativism I am not ignoring the view that values have a role to play in cognitive relativism – an issue I shall discuss below. Relativism is also sometimes confused with scepticism. I’ll discuss this in some detail in Chapter 4. Briefly, cognitive relativism rejects some of the assumptions held by sceptics and so rejects scepticism itself, making space for legitimate, fallible, alternative conceptions of reality.

On a question of terminology, relativism is generally contrasted with its polar opposite: absolutism. Calling something relative is to say that it arises from or is determined by something else; it is dependent on its relation to some other thing. Something absolute is independent and doesn’t require relationship to anything else. However, this is a very general and not very informative characterization. The sorts of dependence and independence in question may be of very different kinds. I shall examine in more detail specific forms of cognitive relativism in this chapter in “The cognitive relativism family” (pp. 19–24), which will serve to make more concrete what is involved. However, the point I want to make here is that the terms “relative” and “absolute” will be used thoughout the rest of the book as opposed terms. So anti-relativists will be characterized as absolutists.

Another term sometimes used instead of relativism is “pluralism”. This characterizes the situation where there are alternatives – where there is more than one canonical or valid account of reality. As will become clearer in the remainder of the book, I hold that some forms of relativism are rationally acceptable, and others are not. The term “pluralism” may be taken as synonymous with those forms of relativism that are acceptable and I will not dwell any further on this essentially terminological issue. But now, before presenting different kinds of cognitive relativism, I will examine some key positions in twentieth-century philosophy that paved the way for relativistic thinking.

Sources of contemporary relativism

A distinctive feature of twentieth-century philosophy has been a series of sustained challenges to dualisms that were taken for granted in earlier periods. The split between mind and body that dominated most of the modern period was attacked in a variety of different ways by twentieth-century thinkers. Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Wittgenstein and Ryle all rejected the Cartesian model, but did so in quite distinctly different ways. Other cherished dualisms have also been attacked – for example, the analytic–synthetic distinction, the dichotomy between theory and practice and the fact–value distinction. However, unlike the rejection of Cartesian dualism, these debates are still live, with substantial support for either side.

While a reasonably unified philosophical community existed at the beginning of the twentieth century, by the middle of the century philosophy had split into distinct traditions with little contact between them. Russell, Husserl and James had been aware of each other’s work. However, the traditions following on from them tended to operate by and large in ignorance of each other. The English-based tradition of Russell–Wittgenstein–Ryle–Austin and the American-based tradition of James–Lewis–Quine–Putnam did interact with each other, but left alone the Husserl–Heidegger– Sartre–Derrida tradition and were likewise ignored by them. It was only towards the close of the century that a more ecumenical spirit began to arise on both sides. Nevertheless, despite the philosophical Cold War, certain curiously similar tendencies emerged on all sides during the mid-twentieth century, which aided the rise of cognitive relativism as a significant phenomenon. I shall address three of these here.

Rejecting the theory-practice dichotomy

In the ancient world, the metaphysical and ethical parts of philosophy were in closer contact than has been the case subsequently. Questions about how one should live and what is the good life led naturally to abstract reflections on being, knowledge and all the other staples of philosophical reflection. The passion for systematization of the medieval period also made for unified accounts of reality, where ethical considerations and prescriptions for conduct were held to derive from the very fabric of reality. Goodness and being were understood as different facets of the same basic reality. However, in the early modern period this unified approach began to unravel. The investigation of the nature of reality began to pull apart from questions about morality. As technological and scientific advances shed greater light on the mysteries of nature, the problem of human conduct and behaviour came to be seen as a more localized problem, one not connected to discussions of the nature of reality.

While science offered accounts of the laws of nature and the constituents of matter, and revealed the hidden mechanisms behind appearances, a split appeared in the kinds of knowledge available to enquirers. On the one hand there were the objective, reliable, well-grounded results of empirical enquiry into nature, and on the other the subjective, variable and controversial results of enquiries into morals, society, religion and so on. There was the realm of the world, which existed imperiously and massively independent of us, and the human world itself, which was complex, varied and dependent on us. The philosophical conception that developed from this picture was that of a split between a view of reality that is independent of human input and reality dependent on human beings. Bernard Williams has labelled the former the “absolute conception of reality” (1978: 64–8). Genuine knowledge is knowledge of that which is there independently of our knowing of it: knowledge of what is there anyway.

Human knowledge is an effort adequately to capture or represent this reality. While different representations of it are possible, the constant impetus of human enquiry is to try to get to a more inclusive representation that can explain localized differences. Philosophers of the modern period worked within this conception in developing and employing the distinction between primary and secondary qualities. Primary qualities are those aspects of reality that are there independent of human cognition – for example, shape, motion and mass. Secondary qualities require conscious awareness for their existence – for example, colours, sounds and so on. The vibrations in the air that hit my eardrum and lead me to hear the traffic outside are explicable in terms that don’t bring in consciousness. However, my hearing the sound requires conscious awareness. So one set of phenomena belong absolutely to the furniture of the world and would be there with no one to know them. Other phenomena are products of human receptivity and consciousness and are therefore dependent on human cognition. These are not part of the absolute conception of reality.

It was thought that philosophy could help the pursuit of the absolute conception of reality first of all by supplying epistemological foundations for it. However, after many failed attempts at this, other philosophers appropriated the more modest task of clarifying the meanings and methods of the primary investigators (the scientists). Philosophy can come into its own when sorting out the more subjective aspects of the human realm: ethics, aesthetics, politics. However, what is distinctive of the investigation of the absolute conception is its disinterestedness, its cool objectivity, its demonstrable success in achieving results. It is pure theory – the acquisition of a true account of reality. While these results may be put to use in technology, the goal of enquiry is truth itself with no utilitarian end in view. The human striving for knowledge, noted by Aristotle at the beginning of his Metaphysics, gets its fullest realization in the scientific effort to flesh out this absolute conception of reality.

This absolute conception of reality came under attack from different quarters in the twentieth century. On a descriptive level, historians and philosophers of science held that it gave a distorted account of how enquiry actually proceeded. Scientists are members of human society just as much as anyone else. They are influenced by fashion, politics, economics, social status, the search for patronage and many other elements from the “subjective” realm. Furthermore, the project of enquiry is not describable in terms of setting out rules and methods, and the histories of the various sciences are littered with stories of chance, intrigue, lucky blunders and wayward genius. So the picture of the scientist as somehow removed from the messy subjective realities of human existence doesn’t hold up. Yet one could still claim that, despite its murky history and provenance, science still delivers the pristine goods: the unpolluted absolute conception of reality. The glory of science is its pulling the objective truth from the murk of human interaction with reality. However, this was further challenged by examining very idea of objectivity used in articulating the notion of the absolute conception of reality.

One problem regularly pointed out is that the absolute conception of reality leaves itself open to massive sceptical challenge. If such a pure de-humanized picture of reality is the goal of enquiry, how could we ever reach it? Surely we would inevitably infect it with human subjectivity in our very effort to grasp it. Therefore we are condemning ourselves to the melancholy conclusion that we will never really have knowledge of reality – a sceptical stance. If one wanted to reject such a sceptical conclusion, a rejection of the conception of objectivity underlying it would be required.

A different notion of objectivity rests on the idea of inter-subjectivity. What is objective is that on which reasonable people agree. Unlike in the absolute conception of reality, one doesn’t have to claim that there is no human input into the picture of reality acquired in enquiry. Rather, as William James put it, “the trail of the human serpent is thus over everything” (1981: 33). This doesn’t render the results of enquiry less objective; it changes our conception of objectivity. We do get in touch with a reality independent of human thought, but mediated via human thought.

How this connects to relativism is that reality can be so mediated in a variety of different ways, which are not reducible to each other. The representations of objective reality may differ depending on the concepts we use to think about it. Different features of reality come to the fore as we deploy different sets of concepts to deal with it. Philosophers from different traditions, such as Wittgenstein, Heidegger and William James, came to hold versions of this view. With such a view, there arises a tension between, on the one hand, a free-for-all approach, where a multiplicity of conflicting views can be accepted with insouciance and, on the other, the drive to limit such proliferation, to exercise some kind of cognitive control on what is acceptable and what is not. We can look a little more closely at some of these ideas in discussing frameworks, below. Meanwhile, this challenge to the sharp dichotomy between theory and practice had the effect of putting another related dichotomy under threat, namely the distinction between facts and values.

Rejecting the fact-value dichotomy

The notion of “fact” is closely tied to that of the absolute conception of reality. Facts are independent, objective, solid, dependable, invariant and reliable. They are to be contrasted with the subjective, mutable and unreliable: emotions, wishes, dreams, delusions and other subjective projections of humankind. One casualty of the dominance of the absolute conception of reality was the notion of value. From its former place as rooted in being, it came to be seen as a kind of projection, a way human beings have of colouring the facts, which exist independently of any such colour. So language can be split into descriptive vocabulary, which articulates the facts, and evaluative vocabulary, which reports our attitude to such facts. Emotivist theories of ethics propose this dichotomy and take the sharp fact–value split as given.

Now on the absolute conception of reality, facts exist independently of human cognition. Nevertheless, in order for human beings to know such facts, they must be conceptualized. We dress the world in concepts in order to think of it. This point is used by those against the absolute conception of reality to challenge it and its associated fact–value dichotomy. The world doesn’t automatically conceptualize itself. The story of the development of human knowledge is the story of the creative development of more and more concepts to articulate the way the world is. However, we develop concepts that pick out those features of the world in which we have an interest, and not o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction to relativism

- 2 Truth and logic

- 3 Ontological relativism

- 4 Epistemological relativism

- 5 Relativism about rationality

- 6 Evaluating relativism

- Guide to further reading

- Bibliography

- Index