![]()

PART I

INTRODUCTION

![]()

1

EVOLUTIONARY THEORY AND THE SOCIOLOGY OF GENDER

A BAD BEGINNING

Intelligent life on a planet comes of age when it first works out the reason for its own existence. If superior creatures from space ever visit earth, the first question they will ask, in order to assess the level of our civilization, is: “Have they discovered evolution yet?”

Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene

This book is an evolutionary approach to gender. It suggests that there are some evolved differences between men and women, besides the obvious physical ones. This does not sit well with some people, including my younger self. I remember overhearing a conversation between my friend’s parents while we were riding in a car—I must have been about 14 or 15 at the time. They were talking about how men and women were equal, but not the same. They were talking about men’s and women’s minds more than anything. I remember sitting in the back seat and saying to myself: that is not true, they are equal and the same! At that age, I was determined to escape the typical adult gender roles I saw about me, and I felt that the idea that men and women were different supported those traditional gender roles. We all grow up, and I did change my youthful ideas. This book is about what I have found out about men and women in my career as a social scientist. Now I would have to say that my friend’s parents were more right than I was at the time. Men and women are equal, but they are not quite the same, in their minds as well as their bodies. Evolutionary theory tells us why. While this does nothing to mandate the traditional gender roles I was so anxious to escape, it can help explain why they exist as they do.

Evolutionary Theory

Evolutionary theory assumes that human beings, like all living things, are the product of evolution by natural selection. That is, our bodies are collections of adaptations that helped our ancestors survive and reproduce in the evolutionary environment. Modern humans evolved in Africa, so the evolutionary environment for humans was Africa in the Pleistocene—the period from around 2 million years ago to about 10,000 years ago when sedentary farming began. Behaviorally modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) left Africa about 50,000 years ago. When humans spread out over the world, there was some small-scale, local evolution for things such as skin color and nose shape, but these things account for a tiny fraction of the human genotype. Humans share the vast majority of their genetic material, and there are larger genetic differences within racial groups than between racial groups (Witherspoon et al. 2007). The largest amount of genetic diversity exists in Africa, which is what you would expect if only a small group left during the diaspora.

Not only was the human body shaped by natural selection, but also the brain and the mind it creates. That is, humans not only all have the same general body shape and size, but also a common emotional makeup (Turner and Maryanski 2008). Closely tied to our emotional makeup are predispositions toward certain behaviors and preferences that all humans share. What I am saying is that there is a human nature, and it is universal.

Humans have the emotions and associated predispositions they do because they were adaptive in the evolutionary environment, that is, they helped individuals survive and reproduce in that environment. As we saw above, the evolutionary environment for humans was Africa (most likely East Africa) during the Pleistocene, and it is to that environment that humans are adapted. So what was it like in Africa back then? It was the Stone Age, so people were hunting, gathering, and fishing. We don’t know what these groups were like, but we can infer some of their characteristics from the anthropological studies of hunting and gathering groups that survived into more modern times. Our Stone Age ancestors were most likely living in small nomadic groups no larger than about 150 or so people. Like all hunters and gatherers, they would have followed wild game around as it moved from place to place. They would have also gone to where other wild foods (fish, roots, nuts, berries, eggs) were most abundant. These groups were likely highly egalitarian. People would have had few possessions, and there would have been no permanent houses, given that people moved around a great deal of the time. There would have been no way to store food, and so all fresh food (particularly meat that can spoil) was likely shared among all the members of the group, as is common in groups of hunters and gatherers studied in recent times.

It is to this environment that our bodies and brains are adapted. A good example of an adaptation is the one that produces the universal taste for sweets, fats, and salts. People in all cultures enjoy these things, although often in different forms. In East Africa in the Pleistocene, a predisposition that encouraged the consumption of sweets, fats, and salts was adaptive because these things were scarce. Sweets and fats come packaged with other nutrients that are essential for survival. Sugars come in fruits that contain vitamins and minerals essential for our health; fats come in meats that contain proteins essential for growth and wellbeing. Those individuals who had a taste for sweets, fats, and salts, and who consumed as many of these things as possible when they were available, were more likely to be healthy. They were also more likely to endure periods of famine, scarcity, and sickness, so they were more likely to survive and reproduce than those who didn’t. This meant that those people with an inbuilt taste for sweets and fats were more likely to have children, and hence pass on their inbuilt takes for sweets and fats to their descendants—that is, to us. That is why we all like sweets, fats, and salts so much. Of course, in a modern environment where these things are no longer scarce, this is something of a problem. Tastes that once were healthful are unfortunately no longer so. It is important to remember that for about 90 percent of human history, people were living as hunters and gatherers. We have only lived in modern industrial societies for the blink of an eye in evolutionary terms—there has been no time for evolution to catch up.

Another example of an adaptation is a predisposition to fear of snakes. Most children quickly develop a fear of snakes, although of course there is variation from child to child. This is not surprising, as throughout evolutionary history, snakes were a real threat to humans. Fear is an adaptive response as it promotes withdrawal from any snake, hopefully out of harm’s way. Throughout evolutionary history, such fear likely saved the lives of many people, thus ensuring that the predisposition toward fear of snakes was passed on to future generations. Because of this predisposition, children today quickly learn to fear snakes, although most children in modern urban environments are unlikely ever to be threatened by a snake. Cars are much more of a danger to children in the modern environment, but most children do not quickly develop a fear of cars. Once again, we have lived in a modern environment where cars are more of a threat than snakes for just a blink of an eye in evolutionary terms, and there has not been time for evolution to catch up. This means there has not been long enough for selection of traits, such as fear of cars, and for those traits to spread throughout the population.

It is important to note that many evolved predispositions, such as the taste for sweets, fats, and salts or fear of snakes, are not necessarily currently adaptive or even advantageous to humans in the modern world. Predispositions such as the ones that promote a love of sweets, fats, and salts or fear of snakes are often unconscious. That is, we don’t choose to like sweets, fats, and salts and fear snakes; we just do. People often are not aware of their own predispositions, and only know of them when they are in the situation that activates that predisposition—for example, they are confronted with a large, luscious slice of chocolate cake; or perhaps the sight of a snake in the backyard. People are also often aware of the emotions that predispositions promote—for example, longing or fear.

Evolved Predispositions versus the Blank Slate View of Human Nature

The evolutionary view of human nature, as sketched out above, is very different from the view of human nature as a malleable substance that is given the entirety of its form by the culture an individual is brought up in. The evolutionary view of human nature is that the culture does shape human nature, but it is has to work with the material given, and this cannot be shaped into just anything. This means that cultures are not infinitely variable, and there are true universals and common patterns across human societies. These include things such as the fact that, with a few rare exceptions, humans live in groups, that is, we are a social species. All societies have some sort of social hierarchy where people in the group are ranked in some sort of way. Besides sociality, there are a large number of other human universals. For example, all humans have language. There are universal facial expressions—all humans recognize the smile, for example. Incest taboos are universal. The predisposition to favor the use of one hand (usually the right hand) is universal. The list goes on (Brown 1991).

So rather than being a blank slate, or a computer that can be programmed to do anything, human nature is best seen as a computer that comes bundled with software (predispositions). This software was designed to solve problems faced by our ancestors in the evolutionary environment. Those problems can be grouped into five general types of problems that our ancestors needed to solve in the evolutionary environment if they were to leave genetic descendants:

-

Problems of survival

These are the problems of getting enough food to eat, defending oneself against human and nonhuman predators, and avoiding disease and accidental death. Individuals who did not manage to do this were unlikely to leave descendants.

-

Problems of mating

These are the problems of finding and keeping a mate and doing what was necessary for successful reproduction in the evolutionary environment.

-

Problems of parenting

The problems of helping offspring survive, grow, and reproduce.

-

Problems of aiding genetic relatives, not just children.

The problems of helping others who carry copies of our genes. Even if an individual does not successfully reproduce, they can still leave descendants if they help other people who are genetically related to them. The more relatives an individual helps, the greater the number of genetic descendants he or she is likely to leave.

-

Problems of group living

This is solving problems in relationships with others, learning group rules or culture, and earning status within the group. In early human groups, these problems had to be solved in order to successfully solve the first four problems. In the environment of evolution, a solitary individual was unlikely to survive very long and, by definition, would not have a mate.

Individuals who did not solve these problems in the evolutionary environment were less likely to survive and leave genetic descendants. Individuals who successfully solved these problems were more likely to survive and leave genetic descendants. This means that genes for predispositions for traits that helped individuals solve these problems repeatedly over evolutionary time were selected for, and have become universal in, the human population. Alternatively, you can think that individuals without genes for such predispositions were less likely to solve those problems and thus less likely to leave genetic descendants. Thus, an evolved predisposition exists in the form it does because it repeatedly helped solve a specific problem of survival or reproduction over evolutionary history.

We don’t have predispositions for things that did not solve problems in our evolutionary history. For example, in our evolutionary history, sweets, fats, and salts were scarce, but fiber was not. There was no scarcity of fiber, and obtaining enough fiber in the diet was not a problem our ancestors faced, so liking fiber has not emerged as an evolved predisposition. So even though having fiber in our diet is crucial, we do not have the spontaneous liking of fiber to match our spontaneous liking of sweets, fats, and salts. Once again, this is a problem in a modern environment where the abundance of foodstuffs means we can avoid fiber if we want, to our detriment.

Another predisposition we don’t have is a strong desire to have children, even though for obvious evolutionary reasons we have a strong predisposition to desire sex. As Richard Dawkins (2013, p. 165) puts it: “It isn’t difficult for a biologist to explain why nervous systems evolved in such a way as to make sexual congress one of the consistently greatest experiences life has to offer.” In the evolutionary environment, there was no effective contraception, so having children was not a problem, given the strong desire for sex. People had sex and children naturally followed. In the modern era, the comparative lack of desire for children (coupled with the modern environment and lifestyle) and the availability of effective contraception means people can have sex and no children, with the result being a very low birth rate. Note that this doesn’t mean people don’t want children, just that the desire to have children is not as strong or as universal as our evolved drive to have sex.

Predispositions and Actual Behavior

The existence of predispositions does not mean that people have no choice in what they do. Think of the evolved predisposition for liking sweets, fats, and salts. Then think of a situation where we are confronted with a large piece of chocolate cake. We find that it looks good, and we want to eat it. But we don’t have to eat it! We may decide not to eat it because we don’t want to spoil our appetite for dinner, or because we are trying to lose weight or trying not to gain weight, or because we have been told that the cake is poisoned. Alternatively, think of a situation where we have been told by our doctor to include more fiber in our diet. We know we ought to buy the high-fiber bread, but we prefer the taste of the white (low-fiber) bread. But, given what the doctor has said, we go ahead and buy the high-fiber bread and eat it.

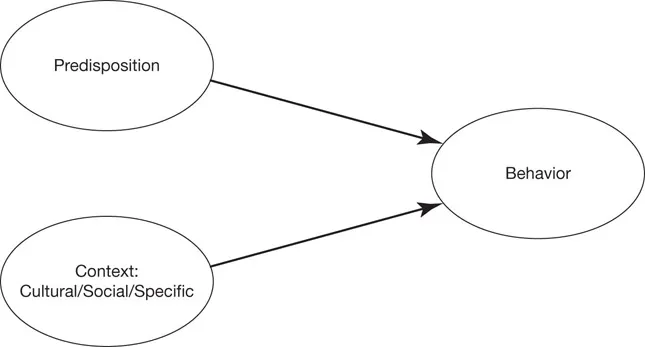

That is, actual behavior is always a result of a decision-making process that includes input from predispositions as well as the context of the individual. Context includes the cultural context, e.g. whether gaining weight and being heavy is regarded as high status or low status in the culture; the social context, e.g. other people are all being polite and not taking the last piece of cake so you feel you cannot take it; and the specific context, e.g. you have been told that particular cake is poisoned. Predispositions are just one factor in behavior; they are not the only one, and often they are not the most important ones. But the point is they are always a factor.

Figure 1.1 Determinants of behavior—an evolutionary view

Common Misunderstandings about Evolutionary Theory

There are several common misunderstandings of evolutionary theory.

-

Genes determine our behaviour

Evolved predispositions exist in our genetic makeup as humans, but this does not mean that everything we do is determined by them. As noted above, predispositions are just one factor among many that determine what an individual decides to do. Each individual reacts to their own particular situation. Behavior is always a product of a particular predisposition and the environment of the individual at the same time.

Individuals can consciously override their predispositions. For example, the predisposition to like sweets, fats, and salts is real, but individuals can consciously avoid these substances when they go on a diet.

-

If it’s evolved, we can’t change it

This is simply not true. As just noted, we can override any particular predisposition, although we might find it difficult! In fact, often k...