![]() Part 1

Part 1

What is interactional leadership?![]()

Prologue

The choice-focused leader

What is interactional leadership?

All leaders make choices but not all leaders are choice-focused. The concept of choice-focused, or interactional, leadership is really not complicated. It simply refers to leaders who are sufficiently in touch with reality to act on it effectively. It is the philosophical definition of reality, in all its complex, multiple dimensions and changing forms, which is more of a problem. Perhaps that is why a commonly accepted definition of good leadership has eluded thinkers and practitioners from Plato onwards. So I want to begin this book not with theory but with a concrete situation, which I hope gets to the heart of the real challenges of being a leader.

Carl is the chief executive of an international telecoms company. As we meet him for the first and only time, he is sitting in his luxurious office, high above the glittering River Thames, bright and early one Monday morning. Carl’s head is already buzzing with issues. There is a strong rumour of a possible hostile takeover by a long-standing rival, which he dismisses with snort of anger. He ponders whether to give the green light to a major project to develop a new type of mobile phone. This, he hopes will prevent him from having to close down several manufacturing operations throughout the world, which are reporting continuing production problems. Can he obtain the funds from his bankers for the project? He checks the latest interest rates forecast, before reading several emails from irate shareholders urging him to downsize the company, at which he feels a surge of frustration. He thinks about finishing his speech for an industry conference, attended by many City analysts, in which he wants to promote his new vision for online security, and boost his company’s sagging share price.

Turning to his diary, Carl sees he has a disciplinary session that morning with his marketing director, who is facing a recurrent bullying complaint. Somewhat uneasily, Carl decides to delegate this meeting to his human resources director. There is a potentially fractious lunch with his chairman and a final interview for a much-needed new finance director. And he sighs, as he realises that he is scheduled to have dinner with an influential customer at the same time as his daughter’s school play. He imagines his wife’s fury if he misses yet another family event. He glances at his watch: 7.45am. His working week has barely started.

In this snapshot, what I would ask you to notice, first of all, is the sheer range of interactions which frame Carl’s world. There are interactions with people, such as his employees, his customers, his shareholders, his chairman and his wife. There are interactions at the level of ideas, as represented by his plans for online security, and material interactions, like potentially closing down factories or creating new products. Carl’s financial interactions encompass the entire world economy, as he ponders whether he can afford a huge loan, as do his business interactions, as he dismisses the rumour of a takeover by a multinational rival. And there are also interactions at the more impenetrable levels of knowledge, in terms of what Carl knows and does not know – or prefers not to know.

These interactions make themselves apparent to Carl as matters of interpretation with implications for action. In other words, they enter his consciousness as choices. There are choices about strategic development, choices about funding, about how to respond to frustrated shareholders. There are human resources choices, involving the selection of a crucial leadership team member and perhaps the dismissal of another one. There are personal choices about his values and beliefs (e.g. his resistance to downsizing), which are also influenced by his emotions (his disdain for his putative takeover rivals) and his family relationships. There are choices about delivery, in relation to production hold-ups and to the many people in his company’s vast supply chain.

But not all of Carl’s choices are fully conscious. There are choices which he seems to be avoiding, such as dealing with his marketing director’s problematic behaviour or the reorganization of his overseas factories. And of course, there are always other choices which he might be making but is not. What is certain, is that all these choices are flowing into and through and past Carl’s consciousness at a furious pace, in a seemingly continuous present, which has potentially huge implications for the future of many people (not least for Carl himself).

In short, Carl is making – and not making – choices. He is a leader, what else would he do? But is he making balanced, effective choices? The answer, unfortunately, is: no. By the time Carl entered coaching with me, the snapshot, which I have imaginatively reconstructed here from our conversations together, was a distant memory. All that remained of his career was for him to manage a dignified exit from his company.

In our sessions, Carl realised why he had fallen off the leadership tightrope. In part, it was due to his confused strategy in relation to new products and his mishandling of aspects of the production process. He had allowed the failings of his marketing director to go unpunished, which had soured relationships within his management team, and he had done nothing to repair the conflict with his chairman, which had turned a potential ally into a foe. Above all, Carl realised – what everybody knew by then – that he had been too emotional in dismissing the possibility of a takeover by the rival company, because this eventually took place, costing him the job he loved. Carl was highly intelligent, knowledgeable, energetic and even charismatic. But he was not adept at the art of balancing choices. In short, he was not a choice-focused leader.

This book is about the art of choice-focused leadership and how to coach it. It is about helping leaders to manage the interactions of the world they find themselves in so as to bring about positive results. This requires them to be successful in many of their key choices. Former supermarket chief executive Alan Leighton (2012) is probably correct in saying that an effective leader only needs to get 70 per cent of his ‘tough calls’ right; except, it has to be said, if too many of the 30 per cent he gets wrong are the ones that really matter (which was Carl’s fate). Navigating the shifting border that separates success from failure, buffeted by powerful interactions which come at him from every angle (including from within): this is the leader’s true challenge. Mastering it requires the exceptional expertise in choice-making that I call interactional leadership.

The dialectic of organizational achievement and psychology: leading in 6D

Interactional leadership theory attempts to generalize about choice-making and the interactional reality in which a leader has to make his or her choices. Some might say this is impossible, a view which the sheer number of theories of leadership which have been produced throughout history might seem to endorse. The multitudinous times and places of leadership certainly complicate a conceptual account of the subject, as do its many different realms in business, the public sector, government, science, religion and the arts. The plenitude of metaphors for leadership sounds another warning. General and servant, symphony conductor and jazz musician, sports coach and circus ringmaster: this is only a tiny sample of the conflicting images of leadership which have been used over the years. Some might even say that the practice of leadership coaching endorses a kind of situational relativism, in that it highlights the uniqueness of a leader’s personal and professional context. And yet in spite of this profound diversity, I believe there are some structures and categories which we can use to frame leadership, which makes the tasks involved in practicing and coaching it a little easier. This is certainly the intention of my approach: to provide guidelines for leaders and coaches, while never obscuring the fact that leaders’ choices are their own.

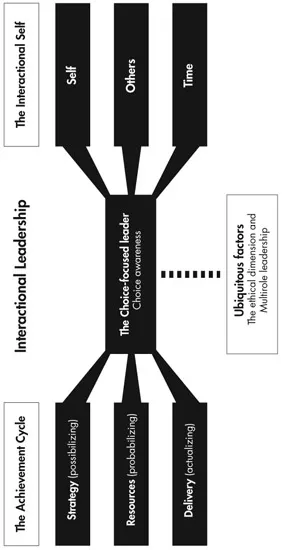

At the core of the interactional leadership model is the relationship between two concepts. One is the Achievement Cycle, the combination of strategy, resourcing and delivery which lies behind any successful organizational process. The other construct in this dialectical, dual-core relationship is the Interactional Self, the psychology of the leader, made up through the dynamic relationship of self and others in time, which draws on existential and cognitive psychology and interactional forms of thinking (which I’ll say more about in Chapter 3). Constructive interaction between the Achievement Cycle and the Interactional Self produces positive results and a new reality. Two other factors are ubiquitous in this model, which has emerged out of my experience of coaching leaders for the best part of twenty years: the ethical frame of leadership (an extension of general choice-making) and the multirole of leadership.

Fundamentally, interactional leadership amounts to a process of leading in six dimensions (6D), as illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 on the next two pages.

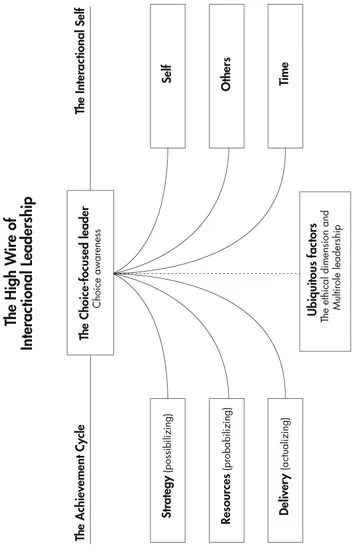

On the left of Figure 1, you will notice the Achievement Cycle, representing the business-based, organizational reality of leadership, on the right, the Interactional Self, which is a philosophically-informed psychology of leadership. The leader’s success depends on her ability to fuse these structures together through her choice-making. Figure 2 provides an alternative visualization of exactly the same model, which emphasizes the fluid and dynamic nature of this balancing act. In Chapter 2, I’ll say more about the psychology of the balancing art of leadership but first let us turn to the kind of choice awareness involved in becoming an effective leader and the meaning of the Achievement Cycle.

Figure 1 The Interactional Leadership model

Figure 2 The Interactional Leadership model (High Wire version)

![]()

Chapter 1

The Achievement Cycle and the art of leadership choice-making

The hierarchy of choice

Life is about choosing. From the interactional standpoint, we make ourselves through our choices every hour of every day. Existentialist philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre (1958: 448) expresses this profound idea when he says, ‘to be is to choose oneself’. But not all our personal choices are of equal significance. Some are relatively trivial, forgotten almost immediately; others play a major part in determining who are and who we will become. In this latter category are our choices about what we believe in, who we love and want to live with, whether we want to become parents and how we want to earn our living. Nor are all of our choices within our immediate control. We are propelled into the world at a certain time and place which is not of our choosing, with specific familial, social, economic, cultural and biological attributes, but it is up to us what we make of the factors which make us.

In life’s hierarchy of choice, leadership has an especially elevated status. In the main, the typical organization is structured around the amount of choice-making freedom its employees are granted. Unskilled workers largely follow routines and timetables which have been chosen for them. Administrative employees have more discretionary power and, as we rise through the organization’s executive ranks towards senior management, we find that different degrees of decision-making translate into ever more significant distinctions of power and responsibility.

At the top of the organization, with the greatest range of choices, sits the leader. On behalf of others, she makes choices which can have huge consequences for the lives of many people, perhaps for tens of thousands, in the case of a corporate leader or many more, when it comes to political leaders. These choices not only influence everyday lives but also create the shape of what is to come. In a very real sense, leaders choose the future.

Of course, there is a case in organizations of every kind for redistributing some of these choices down the hierarchy – and at times I’ll make that case, because, apart from anything else, it is often in the interest of leaders to do so. But the truth is that we appoint our leaders to make the choices which we cannot make ourselves, partially for practical reasons, and partially, if we are honest, because many of these choices are extraordinarily challenging. As voters, we retain some influence on governmental and public sector polices, and as employees, consumers and shareholders we may have a small say in the direction of corporations. But when the waves of a long economic boom finally crash to the shore, and the decisions of the good times – with their lavishly generous margins of error – give way to the painfully tight decisions of the bad times, we realise just how important these delegated choices really are and how necessary it is to help leaders get them right in the future.

The anatomy of choice

Choice-making is an art not a science. Although the term ‘choice science’ is increasingly used and scientific studies are giving us more information about this most complex of human activities (as we’ll see in Chapter 3), in my view it seems unlikely that choice-making will ever be something that we can completely predict or learn by rote. It will always be intimately bound up with the exigencies of a particular human experience. Nevertheless, choices can be usefully analysed in various ways, in terms of their content (which I call the dimensions of choice), process, method, order and outcome. They can also be seen in terms of degrees of conscious awareness, as it is often prereflective choices, which have not been fully identified by consciousness, that have the most impact.

Possibilizing, probabilizing and actualizing

From an interactional viewpoint, the choice-making process is a three-stage transformation of a possibility into an actuality. The first stage of this cycle, possibilizing, is about stretching the boundaries of the imagination, playing with many options, coming up with wide-ranging creative solutions and using one’s imagination to go beyond the status quo. The next stage, probabilizing, is about increasing the likelihood of an idea becoming a reality by making realistic choices, anticipating the resources which are necessary, and devising an action plan that turns the possible into the probable. The final stage, actualizing, is about making the plan happen and doing all that is required to make an idea real. Interactional choice-making therefore involves more than rational decision-making.As philosopher Renata Salecl (2010: 42) says ‘the idea of rational choice, transferred from economics, has been glorified as the only choice we have.’ In fact, real choices involve emotion as well as thought and are indissolubly linked to action.

The choice cycle has many implications for leaders. For example the leader who is strong at possibilizing may be better at coining bold ideas than at making things happen. The probabilizing leader may shy away from developing adventurous ideas, being too concerned with probabilities to challenge the status quo. He may engage in incremental thinking or what has been termed ‘the science of muddling through’ (Lindblom, 1959), which can be described as too much probabilizing and not enough possibilizing. Throughout this process, a leader has vital decisions to make about the ‘how’ of choice-making and the ‘who’. Choice-making styles range from a unilateral approach, in which the individual leader has the final say on everything, to a multilateral style, in which the group makes all the decisions that matter.

All this implies another balancing act which the choice-focused leader needs to master, prioritization, or the principle of renunciation. This is the ability to focus on what is truly significant and reject what is not. Spread your attention too evenly across your objectives and you may fail to actualize the most important ones. As Steve Jobs once said: ‘Deciding what not to do is as important as deciding what to do’ (Isaacson 2011: 336).

Choice awareness

Underpinning the art of balancing choice is choice awareness or ‘optative awareness’, the interactional leader’s knowledge of her own values and strongest desires. Optative awareness develops into a strong sense of what works and what doesn’t and a feeling for when equipoise in a situation has been reached or has started to come apart. This ‘super-reflective’ consciousness (Harvey, 2012) involves a high level of attention and bears some similarities to what cognitive psychologist Daniel Kahneman (2011) terms ‘slow thinking’, which can often see through the rapid biases and short cuts which dominate ordinary consciousness. Choice-focused thinking also includes meta-choices or the ability to choose how to choose. It may feature simultaneous recognition of the forms of decision-making appropriate to a particular decision and the content involved in it. A leader cannot ‘have eyes in the back of his head’ – as one entrepreneur complained to me during a particularly vicious bout of infighting among his shareholders – but the accomplished choice-focused leader can at times achieve a kind of context-bound 360-degree vision. For this reason, he can rightly be called a virtuoso in choice-making.

The best possible choices are the most informed. Nothing can guarantee a positive outcome but the choice-focused leader engages in processes that are more likely to produce positive outcomes than poor decision-making processes. As human beings, we cannot know what is unknowable in a situation and the role of chance in determining the course of events should never be underestimated. Ineffective leaders do not get every outcome wrong. Sometimes that most precious of leadership attributes, good luck, comes to their aid or the sheer frequency of their poor decisions increases the possibility of a lucky strike. But we should beware of ‘the pernicious effects’ of hindsight which, as Kahneman reminds us (2011: 203), erroneously leads observers ‘to assess the quality of a decision not by whether the process was sound but by whether the outcome was good or bad’. By failing to balance their choices, and by selecting the wrong content, uninteractional leaders increase the likelihood of making unreflective, unconsciously biased decisions, and this significantly raises the probability of poor overall outcomes

The Achievement Cycle

The achievement cycle is the principal theatre in which the choice-focused leader operates. It involves strategy, a future-directed set of possibilities, resources, all that makes more probable the success of that strategy, and delivery, which actualizes it by turning it into an organizational reality. The cycle can be seen as a dia...