![]()

PART I

The role of working memory in development

As mentioned in the Preface, the concept of working memory was introduced by Miller et al. (1960) as a kind of mental space, located somewhere in the frontal lobes of the brain, corresponding to a quick-access memory able to hold temporary, transient plans for guiding behaviour, in the same way as programs govern the successive operations of a computer. This store, in which information could be represented and remembered while executing the operations of the selected plan in Miller et al.’s terms, has been more recently described as the hub of cognition (Haberlandt (1997), or ‘perhaps the most significant achievement of human mental evolution’ (Goldman-Rakic, 1992, p. 111). Indeed, its central role in selecting, temporarily holding, and processing information relevant for ongoing cognition makes it the keystone of cognitive architecture. Thus, it does not come as a surprise that many authors have viewed in working memory and its development one of the main, if not the main, factor of cognitive development.

However, the long-lasting immersion of cognitive psychology in the information processing approach should not lead us to forget that intellectual development was, for a long time, conceived and theorized without any recourse to the idea that the increase in capacity of some central system allowed for greater intellectual achievements with age. The most prominent example is provided by Piaget, who conceived development as resulting from a process of equilibration that allowed for the integration of more and more complex operational structures. Chapter 1 describes how, with the advent of the information processing approach, what was initially conceived as the result of an equilibration process was progressively envisioned as the consequence of an increase in mental capacity, called by Pascual-Leone (1970) the central computing space M. It could be considered as paradoxical that those theoreticians known as neo-Piagetian, who were the closest to the Piagetian approach, were at the same time those who have ascribed to working memory the most important role in cognitive development. However, this was rather natural for these authors who aimed at overcoming the limitations of Piaget’s theory through its synthesis with the information processing approach. Piaget envisioned intellectual development as the assembly of increasingly complex structures through the coordination and integration of more basic elements like schemes. Thus, assuming that the integration of an increasing number of schemes was made possible by the increase in capacity of the working memory in which these schemes are assembled and coordinated was an ideal solution. Chapter 2 analyses two of the most remarkable attempts to integrate the concept of working memory within a Piaget-inspired structural framework, namely those of Case (1985, 1992) and Halford (1993). Although neo-Piagetian theories are probably those that have ascribed to working memory the most important role in cognitive development, several theories and models focusing on specific domains have also explained development in terms of an increase in working memory capacity. The presentation of some of these domain-specific models makes the subject of Chapter 3, in which is discussed the possibility of reducing cognitive development to the development of working memory.

![]()

1

THE EMERGENCE OF WORKING MEMORY IN DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY

From constructivism to cognitivism

The cognitivist revolution at the turn of the 1950s has had such an impact in our conception and understanding of cognition and its development that it is nowadays difficult, maybe impossible, to envision cognitive functioning without any recourse to notions such as cognitive resources and capacities. If thinking is a matter of selecting and encoding relevant items from the continuous flow of information in which we are immersed, and to process the resulting representations in a way appropriate to reach our current goals, the amount of information that can be processed and the efficiency of this processing, that is the capacity of the channel of information that human mind constitutes, becomes a key aspect of human cognition (Miller, 1956). Within this theoretical stance, individual and developmental differences are naturally seen as resulting from variations in some general capacity to temporarily store relevant information (Cowan, 2005), set aside intruding irrelevant aspects (Zacks & Hasher, 1994), lock the system on the pursuit of current goals (Engle, 2002), and efficiently (i.e. rapidly) process this information before its corruption and vanishing (Kail, 1991; Salthouse, 1996). Most of these limitations have been attributed to a central system of the cognitive architecture called working memory, in which representations would be temporarily stored in view of their processing (see Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974; and Miller, Galanter, & Pribam, 1960, for seminal illustrations of this concept). Exercise allied with maturation would progressively alleviate these constraints, making cognitive functioning more and more efficient. These ideas are so profoundly entrenched in contemporary psychology that it becomes increasingly difficult to imagine that, for decades, developmental psychologists have thought in a different way. This was nonetheless the case for Piaget’s theory that dominated the field of developmental psychology during a large part of the twentieth century.

Cognitive development without working memory: Piaget’s theory

Although the notion of information was extraneous to his theorizing, the fact that young children are limited in their capacity to efficiently process information, that is to take into account and integrate all the relevant aspects of a situation, did not escape Piaget. In one of his first books (Piaget, 1923/1971), he noted the incapacity of young children to handle judgements of relations, as for that boy who explained that there were two brothers in his family and that, consequently, he had one brother, Paul, but denied that Paul himself had a brother. This incapacity to understand relative notions was attributed by Piaget to the egocentrism of child’s thought, the tendency to take as absolute his or her own immediate perception, whereas relative judgements require consciousness of at least two objects, to take into account two different points of view at the same time. Piaget initially explained this phenomenon by the narrowness of the child’s field of attention, which also explained limitations in transitive reasoning or part-whole comparisons (Piaget, 1921, 1923). In this initial view, egocentrism and narrowness of the field of attention both resulted from a certain number of habits or schemas of thought that were described as realistic in analogy to the illusions occurring in the history of science. Realism, the naive belief that our senses and perceptions provide us with a direct access to the world and its comprehension (e.g. the sun that seems to rotate around the earth), was conceived by Piaget as one of the main characteristics of intellectual egocentrism (e.g. 7-year-old children believing that the moon or the sun follow them in their walks). These primitive habits of thought lead children to see many things, often more than adults do as Piaget noted, but being unable to organize these observations, they cannot think of more than one thing at a time due to a synthetic incapacity.

These primary ideas were further developed during decades within the operational theory of intelligence and received their final formulation 50 years later in The equilibration of cognitive structures (Piaget, 1975/1985), which was considered by Piaget as the central problem of development. The main idea of this book was that the development of knowledge results not only from the experience with objects, nor from some innate and preformed programming within the subject, but from successive constructions. The mechanisms underpinning these constructions are regulations that compensate the disequilibrium that continuously occur in cognitive functioning and structures, due to the actions of the subject and their (never entirely anticipated) outcomes in the environment. A key point for Piaget was that these regulations do not lead to static forms of equilibrium, but to re-equilibrations improving the previous structures through a process known as majoring equilibration. A general model of the functional aspects of equilibration was proposed and formalized. We will present it in some detail for two reasons. First, its analysis questions the possibility of a continuity between Piaget’s constructivism and information processing approaches that seem to be in a relation of incommensurability. Second, we will encounter later in this book some modern equivalent of this equilibration model in current attempts to account for the development of executive functions (see Chapter 6, and Zelazo, 2015).

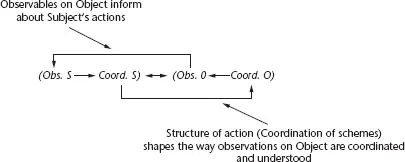

The starting point of Piaget’s analysis is a general model of the Subject–Object interactions. In this model, observables related to the objects (

Obs. O) inform observables related to the subject’s actions (

Obs. S) through a process of awareness of these actions. Conversely, the coordination of the subject’s actions (

Coord. S, i.e. the coordination of schemes in pre-operations and operations) shapes the way in which observables related to the objects are coordinated (

Coord. O), a coordination requiring to go above and beyond the mere observables to understand their relations (e.g. in a causal explanation,

Figure 1.1; see Barrouillet & Camos, 2017). The symbol

in

Figure 1.1 represents a global equilibrium that can be either momentary or lasting.

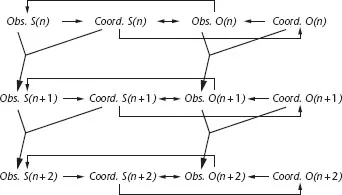

According to Piaget, two characteristics of these interactions lead to a recursive process of equilibration. The first is that observables do not correspond to a mere registration of pre-existing objects or properties that could be directly read out from reality, but depend on the degree of elaboration of the available schemes and their coordination at the previous developmental level,1 leading to inaccurate or erroneous observations. The second is that, as long as the models constructed by the child are not sufficiently accurate, the existing coordinations would sooner or later produce the discovery of new observables. Thus, the initial states of interactions only reach unstable forms of equilibrium prone to perturbations and contradictions. Three successive developmental levels of compensation, noted α, β, and γ by Piaget, can intervene to re-establish the compromised equilibrium: the mere neglect of the perturbation leading to ignoring or minimizing the importance of the corresponding observable (level α), its integration in a modified system as a new but innocuous variable (level β), and finally its complete integration allowing for a genuine anticipation of its possible variations that means that the integrated element is no longer disruptive (level γ). Each developmental level n provides the observables that will be integrated at level n + 1 (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.1 Illustration of the mechanisms of majoring equilibration in Piaget’s theory of cognitive development

Source: J. Piaget (1975). L’équilibration des structures cognitives: problème central du développement [The equilibration of cognitive structures]. Etudes d’épistémologie génétique, 33, p. 59. Paris, France: Presses Universitaires de France, adapted with permission.

FIGURE 1.2 Successive elaborations of the Subject’s cognitive structures and Object coordination of features in Piaget’s theory

Source: J. Piaget (1975). L’équilibration des structures cognitives: problème central du développement [The equilibration of cognitive structures]. Etudes d’épistémologie génétique, 33, p. 62. Paris, France: Presses Universitaires de France, adapted with permission.

However, and more importantly for our purpose, these different levels in the majoring equilibration process do not reflect some widening of the field of attention, the narrowness of which would have explained the first and immature levels of interaction. For example, in the classical task of conservation of solid quantity, one of two identical balls of clay is stretched into a long oblong shape. The well-known young children’s error is to assume that the modified ball contains more clay. Focusing only on the increased length resulting from the stretching transformation, children neglect the correlative reduction in thickness of the object that is now thinner. Piaget notes that we are here in a situation akin to the perceptual centration with its two main characteristics: on the one hand, the impossibility of embracing all the aspects at the same time and, on the other hand, a systematic distortion that overestimates the aspect on which attention focuses (the increased length) while depreciating peripheral features (the reduced thickness). However, the incapacity to take into account the two aspects of the transformation receives within the theory of equilibration a more elaborate explanation than the recourse to the ‘habits of thought’ that prevailed in the first formulation of the intellectual egocentrism. According to Piaget (1975), the unnoticed aspects of the situation are not simply neglected, and the correlative incomplete conceptualization does not result from some incapacity to grasp all the relevant aspects at the same time within the field of attention. The equilibration model provides us with a more precise reason. According to Piaget, the neglected aspect has been actually ruled out as it contradicted an usual conceptual schema which is that the action of stretching results in having ‘more’, more length, and consequently more matter. What could be seen as resulting from a narrow field of attention is the outcome of a regulation process aiming at preserving the coherence of children’s conceptual system (level α described above). The restricted thickness is perceived, and this observable constitutes a content that exerts a cognitive pressure on the conceptual form (Coord. S) that assimilates the stretching with an increased amount of matter (Coord. O). While this perturbation is the first time compensated by the mere deletion of the perturbing aspect (level α), the further regulations would tend to reduce the perturbation created by this deletion and lead to its compensation by reorganizing the initial concept. In other words, the regulations transform a latent observation into a conceptualized aspect of the situation that empirically covaries with the length of the object (level β), the reduced thickness being finally conceived as the inseparable corollary and predictable effect of the increase in length, opening the door to the understanding of their perfect compensation (level γ).

Beyond the fact that this development is not underpinned by some increase in the amount of information attended, it is doubtful that Piaget’s theorizing can be reformulated within an information processing approach and its quantitative constructs. Indeed, the notion of information presupposes that some aspects of the environment are intrinsically informative for solving a class of problem in a given situation, and that integrating more of these aspects would lead to a better understanding of this situation and a higher level of adaptation. This conception seems to have inherited the empiricist assumption of a pre-structured reality with its subdivisions (the objects, their features, their relations) that have an a priori relevance preceding the acts of thought. However, for the constructivist approach favoured by Piaget, the information processed at each developmental level depends on a process of assimilation that conveys a meaning to the assimilated objects (e.g. applying sensorimotor schemas to an object does not provide the same type of information as conceptual schemas). Moreover, this process itself, allied with the necessary accommodations, modifies the assimilating schema through generalization and differentiation in such a way that the information provided by the assimilation process varies continuously over development, even for what can be considered as the same aspect of the environment. As Figure 1.2 makes clear, the observables on which thinking operates differ in nature from one developmental level to the other....