Virtue: The Basics

What is a virtue? How are virtues different from vices? Do all virtues share the very same features, or are there different kinds of virtues? Let’s begin by considering which qualities might count as virtues. Do qualities like being smart, fair, brave, open-minded, and funny count as virtues? What about enjoying life, caring about others, having empathy, and having good judgment? At one time or another, philosophers have counted all of these qualities as virtues. There is general philosophical consensus that justice (fairness), courage (bravery), temperance (enjoying life), and wisdom (which is connected to having good judgment) are virtues. These four qualities appear on the lists of virtues generated by Plato, Aristotle, David Hume, and much more recently, Rosalind Hursthouse and Linda Zagzebski. But, there are other qualities which appear on some lists of virtues but not others. Wit (being funny), appears on the lists of Aristotle and Hume; being open-minded appears on Zagzebski’s list; and being smart (having a reliable memory and logical skills) appears on Sosa’s list. Any basic account of virtue—one whose primary job is to distinguish virtue from vice—should be broad enough to include all of the above qualities. There is something that all of these qualities have in common—something that makes them virtues, rather than vices.1

We should notice that the qualities above are a diverse lot. Some of them, such as being smart and being open-minded, are primarily intellectual qualities—they are concerned with intellectual goods like truth, knowledge, and understanding. Other qualities, such as being brave, caring about others, and empathy, are moral qualities—they are concerned with a broader set of goods, including the overall welfare of ourselves and others. Cross-cutting the distinction between moral and intellectual is a distinction between hard-wired capacities, acquired skills, and acquired character traits. Some of the qualities above, such as having empathy and being smart, are arguably a combination of acquired skills and hard-wired capacities. Others, such as open-mindedness and courage, are acquired character traits. So, what makes all of these qualities virtues? What do all of these qualities have in common? The rough answer is that they all make us better people. In other words, virtues are qualities that make one an excellent person. Granted, a person can be excellent in a variety of ways. For instance, she can be excellent insofar as she is has a reliable memory; or insofar as she is attuned to the emotions of other people; or insofar as she is open-minded, courageous, or benevolent. But the main point is that whatever diverse features these qualities have, they are all virtues because they are all excellences. In contrast, vices are defects. Vices are qualities that make us worse people. Analogously, there will be a variety of different ways in which one can be a worse person.

These basic accounts of virtue and vice are quite broad. Unlike much work in contemporary virtue theory, which treats virtue ethics and virtue epistemology as separate fields, the basic account above includes both moral qualities and intellectual qualities. It also includes qualities like courage and cowardice, over whose acquisition we exercise considerable control, alongside qualities like reliable and unreliable memory, over which we have relatively little control. David Hume famously includes all of these sorts of qualities—intellectual as well as moral, and involuntary as well as voluntary—on his lists of virtues and vices. Hume (1966) argues that attempts to exclude intellectual qualities from the category of virtues will fail. In his words, if we were to “lay hold of the distinction between intellectual and moral endowments, and affirm the last alone to be real and genuine virtues, because they alone [led] to action” then we would quickly discover that “many of those qualities … called intellectual virtues, such as prudence, penetration, discernment, discretion, [have] also a considerable influence on conduct” (p. 156). Nor, on Hume’s (1978) view, can we exclude involuntary abilities, since some of them are “useful” to the people who have them—some involuntary abilities enable the people who have them to attain good effects (p. 610). For Hume, then, virtues that are intellectual are no less genuine than virtues that are moral; and virtues that are involuntary are no less genuine than virtues that are voluntary. Our basic account of virtue agrees with Hume on both of these points.

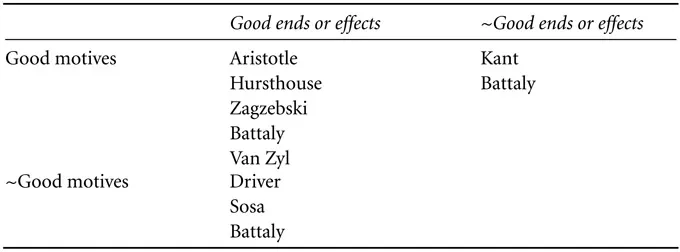

But our basic account of virtue and vice is so broad that it is difficult to apply. To apply them, we need to be able to determine whether a quality is an excellence or a defect, and why it makes one a better person or a worse person. Below, I argue for pluralism; roughly, the view that there are different kinds of virtues. In other words, pluralism claims that different qualities can make one a better person in different ways. One way that qualities can make us better people is by enabling us to attain good ends or effects—like true beliefs, or the welfare of others. But this isn’t the only way for qualities to make us better people. Qualities that involve good motives—like caring about truths, or about the welfare of others—also make us better people, and do so even if they don’t reliably attain good ends or effects. These two kinds of virtue capture two different ways of thinking about virtues—they capture two different concepts of virtue. According to one concept of virtue, which I will call VGE, reliable success in attaining good ends or effects is both necessary and sufficient for a quality’s being a virtue. But, according to another concept of virtue, which I will call VGM, being successful at attaining good ends or effects is not enough, and may not even be required, for virtue. What is required, and what makes a quality a virtue, are good motives. These two concepts (and kinds) of virtue are typically pitted against each other—philosophers have often defended one concept (and kind) of virtue over the other. But, I will suggest that pluralism is a better view; we would do well to embrace both of these concepts and kinds of virtue. In short, both of these concepts succeed in identifying qualities that are virtues.

VGE: Virtues Attain Good Ends or Effects

According to the first concept of virtue, VGE, what makes a quality a virtue as opposed to a vice is its reliable success in attaining good ends or effects, like true beliefs or the welfare of others. Many of these good ends and effects will be external to us. Success in producing them need not be perfect, but must be reliable. This means that qualities that rarely, but occasionally, fail to attain good ends or effects can still be virtues; but qualities that reliably fail to attain good ends or effects cannot. People who try, but reliably fail, to help others (like the character Mr. Bean) do not have the virtue of benevolence. They may want to help others—they may have good motives—but if they reliably and negligently bungle the job, they are not virtuous. Likewise, people who try, but reliably and negligently fail, to get true beliefs do not have intellectual virtues. They may want to get truths—they may have good motives—but if they reliably botch the job, they are not virtuous either. According to VGE, sheer bad luck that is due to no fault of our own can also prevent us from having virtues. People who have the bad luck of being in a demon-world, in which an all-powerful evil demon ensures that their beliefs turn out to be false, or in an oppressive society, in which all or most of their actions turn out to produce harm, do not have virtues. In short, according to VGE, reliably attaining good ends or effects is necessary for a quality’s being a virtue.

VGE also entails that reliably attaining good ends or effects is sufficient for a quality’s being a virtue. Philosophers who advocate VGE argue that good ends or effects are what ultimately matter—they are intrinsically valuable. Accordingly, they think that any quality that reliably succeeds in producing good ends or effects will also be valuable—it will be a virtue. This means that any quality—be it a hard-wired capacity, an acquired skill, or an acquired character trait—will count as a virtue as long as it reliably produces good ends or effects. Accordingly, a hedge-fund manager, who consistently succeeds in helping others via charitable donations, will have the virtue of benevolence, even if he does not care about others and is solely motivated by tax write-offs.2 Likewise, students who reliably arrive at true beliefs as a result of their logical skills will have intellectual virtues, even if they do not care about truth and are solely motivated to get good grades or make money. In short, according to VGE, one need not have good motives to be virtuous; one need only be successful at producing good ends or effects.3

Are VGE Virtues Teleological or Non-Teleological?

Advocates of VGE agree that good ends or effects are intrinsically valuable. But some of them focus on ends; others on effects. So, VGE comes in two different varieties: a teleological variety that focuses on ends, and a non-teleological variety that focuses on effects. Roughly, teleology is the view that things and people have built-in ends or functions. Plato and Aristotle are among the most famous advocates of teleology. They argue that, for example, eyes, knives, doctors, and people in general all have built-in ends or functions. They think that the function (end) of an eye is to see, of a knife is to cut, and of a doctor is to heal the sick. Determining the function (end) of a person in general is a difficult task, even for Plato and Aristotle.

Now, each of these functions—seeing, healing the sick, etc.—can be performed well or poorly. According to the teleological version of VGE, virtues are whatever qualities enable a thing or person to perform its function well (to attain its end). As Plato puts the point: “anything that has a function performs it well by means of its own … virtue, and badly by means of its vice” (Republic, 353c). So, the sharpness of a knife is one of its virtues since sharpness enables it to cut well (to attain its end). Analogously, the virtues of a person will be whatever qualities are responsible for her performing her function well. This means that to figure out which of our qualities are virtues—which of our qualities make us better as people—we must first figure out the function or end of a person.

Other philosophers reject the teleological variety of VGE. They are suspicious of built-in ends and functions, largely for metaphysical reasons. So, rather than define virtues in terms of ends and functions, they define virtues in terms of effects, which do not entail a controversial metaphysics.

In short, advocates of VGE think that virtues are qualities that consistently produce good effects. The challenge for this non-teleological variety of VGE is to figure out which effects are good—which are intrinsically valuable—and why.

Advocates of VGE

Plato is among the most famous advocates of the teleological variety of VGE. In Republic, he explicitly defines virtues in terms of functions or ends. He argues that the function of a person consists in deliberating, ruling oneself, and more broadly, living (353d-e). On his view, virtues are qualities that enable us to perform these functions well. They are the qualities that enable us to deliberate well, rule ourselves well, and thereby live well.

Which qualities are these? To identify the virtues, Plato argues that each person has a soul that is divided into three parts—reason, spirit, and appetite. Each of these parts has its own function. Roughly, the function of reason is to rule the soul and to know what is good for the whole person. This will include knowing which things she should fear, and which things she should desire. The function of spirit is to enforce what reason says about which things she should fear; while the function of appetite is to accept what reason says about which things she should desire (Republic 442c). Of course, each of these functions can be performed well or poorly. Plato thinks that when one’s reason, spirit, and appetite are functioning well, one both knows what is good and puts this knowledge into practice—one fears all and only the things one should, and desires all and only the things one should. To use contemporary examples, one fears combat but not social interaction at parties, and one desires sex but not sex with one’s best friend’s partner. Plato argues that the virtue of wisdom is what enables reason to function well, since the wise person knows what is good and deliberates well. Similarly, courage enables spirit to function well, since the courageous person fears what he should; and temperance enables appetite to function well, since the temperate person desires what he should. Famously, he contends that the virtue of justice is what enables the whole person to function well, and function without internal conflict. On his view, justice enables each part of the soul to do “its own work,” in harmony with the other parts (Republic 441d-e). So together, wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice enable a person to deliberate well, rule oneself well, and thereby live well—they enable her to attain her ends.

Aristotle inherited VGE from Plato. He employs the teleological variety of VGE in Books I and VI of his Nicomachean Ethics (NE), but employs VGM (see below) in much of the rest of NE. In NE.VI, Aristotle explains the intellectual virtues. Like Plato, Aristotle thinks that there is a rational part of the soul and that wisdom is what enables it to function well since wisdom gets us knowledge. But, unlike Plato, Aristotle thinks that there are two types of wisdom and two types of knowledge. On Aristotle’s view, the rational part of the soul is itself sub-divided into two further parts—the contemplative part and the calculative part. The function (end) of the contemplative part is to get theoretical knowledge, which for Aristotle, included truths about mathematics and geometry. Whereas, the function (end) of the calculative part is to get practical knowledge, about, for example, which actions one should perform (e.g., I should study for the exam tomorrow instead of going to the party.). Aristotle uses these two different functions to identify two different sets of virtues. On his view, intellectual virtues are qualities that enable us to perform these functions well—they enable us to reliably attain practical or theoretical knowledge, respectively (NE.1139b11–13). Aristotle identifies practical wisdom (phronesis) and skill (techne) as the virtues of the calculative part—they get us practical truths and knowledge; and philosophical wisdom (sophia), intuitive reason (nous), and scientific knowledge (episteme) as the virtues of the contemplative part—they get us theoretical truths and knowledge.

In Book I of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle also defines moral virtues in terms of functions. In NE.I.7, he argues that the function of a human being is, roughly, rational activity. Aristotle’s notion of rational activity is broader th...