![]()

Chapter 1

Marine Pollution From Oil

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Section 1 Identifying the subject area

1.1 General discussion – challenges relating to marine pollution by oil

1.1.1 Pollution by oil and Port State Control findings

1.2 Key terms/definitions

Section 2 Main discussion of the regulatory framework (MARPOL Annex I)

1.3 Overview of the legal basis

1.4 Structure of the Annex I

1.5 Key resolutions (non-exhaustive list)

1.6 Construction requirements

1.7 Protection of fuel oil tanks

1.8 Control of operational discharges of oil from machinery spaces

1.9 Discharges from the cargo area of oil tankers

Section 3 Key management issues, including documentation

1.10 Surveys and certification

1.10.1 Shipboard Oil Pollution Emergency Plan

1.10.2 Oil Record Book

1.10.3 International Oil Pollution Prevention Certificate

1.11 Relevance of the International Safety Management Code

1.12 Industry best practices

Section 4 Areas of special interest

1.13 Ship-to-ship transfer of crude oil and petroleum products

1.14 Recent developments: oil tankers operations in ice-covered waters (the Polar Code)

Section 5 Selected aspects concerning implementation and enforcement

1.15 Selected highlights on national jurisdictions

Section 1: identifying the subject area

1.1 General discussion – challenges relating to marine pollution by oil

The marine transportation of oil has been addressed by the international regulator long before other substances – an illustration is the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea by Oil (OILPOL 1954), which will be addressed later on in this chapter. MARPOL 73/78, the international instrument of reference on marine pollution by oil, defines oil as “petroleum in any form including crude oil, fuel oil, sludge, oil refuse and refined products […]”.1However, the range of sources of oil entering into the marine environment is broad and is not confined to ships: they range, amongst others, from marine pipelines and dry-docked vessels to coastal facilities (e.g. refineries, storage facilities, etc.), recreational boating, offshore oil and gas exploration and production, and natural marine seeps. Both chronic oil spills from ships’ ordinary operations (e.g. at ports or in busy traffic lanes) and accidental oil spills resulting in small or costly large-scale spills constitute real challenges for regulators, and the oil and shipping industries. It is generally considered that newer ships are cleaner but the way operations are conducted may have an impact on pollution. If the focus is placed on operational discharges of oil from ships into the sea, relevant factors would notably include ship type, age, level of maintenance, use of appropriate equipment aboard and reception facilities ashore, level of awareness and training of the crew, tanker cargoes (for example, in relation to tank washing), etc.

At this point, it would be useful to mention that accidental spillage tends to be coastal and/or unintentional; “accidental” may be understood on the basis of the criterion of time as it results from incidents involving oil release from point sources over a relatively limited amount of time (e.g. hours or days) and can be contrasted with slow leakages of relatively small amounts of oil over longer periods such as months or years.2 As suggested by authoritative studies, estimates on oil inputs at sea are a highly complex task involving questions on methodology, availability, credibility and treatment of data. According to estimates, for the period under examination (by the study), operational discharges from ships represented 45% of the input of 457,000 tonnes/yr. of oil entering the marine environment (ships); according to the same source, shipping accidents had a share of 36% of the input.3

Against this background, the effects of pollution by oil on humans and on the environment have been widely recognised.4 Despite the ability of the marine environment for progressive re-establishment through natural processes, harm may be caused by the oil. Harm may stem from the oil itself and/or the ensuing operations, i.e. response and clean-up. Food chain, marine life and natural resources may be negatively impacted by pollution by oil, thus causing ecological damage and adversely impacting on humans and on their activities (economy, tourism, etc.). There are numerous factors involved with the consequences of marine pollution by oil, including the type of oil concerned (light, heavy and medium oils react differently), the features of the location involved (are sensitive coastal zones and delicate ecosystems involved?), the amount of spillage, sea and weather conditions, time of year of the occurrence, etc.5

Despite the increase of transportation of oil in recent years, a noteworthy reduction during the last decades of oil spilt at sea is generally acknowledged. This positive development may be attributed to a number of factors such as:

- the effectiveness of regulations, including the imposition of strict sanctions that deter non-compliance;

- the advent of modern technologies (e.g. in relation to ship construction or oil recovery from casualties);

- environmental awareness enhancement, including training of the crew and personnel ashore;

- enhancement of the commitment of companies and their personnel aboard and ashore;

- the contribution of numerous stakeholders from the oil and shipping industries through various tools, including best industry practices that support implementation;

- the contribution of non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Lessons learnt from past accidents also contribute to a better understanding of related risks and their handling. A number of casualties have shed light on problematic aspects and have proved to be the triggers of additional and/or better regulations (see, among others, the Torrey Canyon, 1967, and the Exxon Valdez, 1989, respectively in the UK and in the USA).

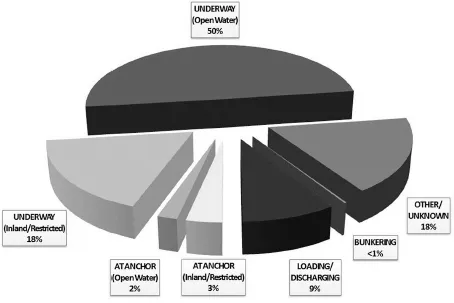

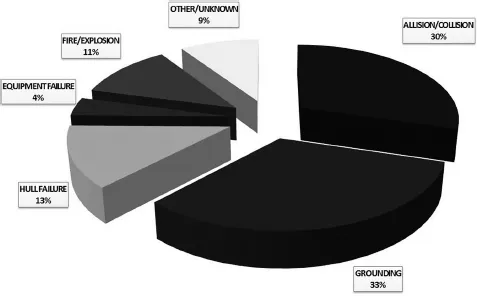

In the graph below the operation at time of incident for large oil spills greater than 700 tonnes (period 1970–2016) is identified. The causes of large spills (>700 tonnes) for the same period are described in the second graph.

Graph 1.1 Operation at time of incident for large oil spills (>700 tonnes, 1970–2016)

Graph 1.2 Causes of large oil spills (>700 tonnes), 1970–2016

A number of large-scale oil accidents have drawn the attention of the public and have prompted regulatory changes internationally and/or regionally. Some of them, involving the shipping industry, are outlined below. Accidents having resulted in more limited spillages in recent years also contribute to the picture.6 Selected accidents involving oil from the offshore sector are briefly touched upon in the chapter which deals with pollution from the oil and gas offshore sector.

- The Torrey Canyon accident (1967)

The Torrey Canyon accident involved an eight-year-old oil tanker flying the Liberian flag laden with crude oil, which ran aground on 18 March 1967 off Cornwall, UK. The vessel’s hull had broken on a reef off the Isles of Scilly. The entire cargo, estimated at 119,000 tonnes of crude oil, was lost. A long section of the Cornish coast was heavily contaminated by the slick. Thousands of seabirds were killed and the accident had extensively impacted on the lives of local communities, tourism and other sectors; in the process, the oil polluted beaches and harbours in the Channel Islands and Brittany, France.

The accident had taken place in fine weather and was attributed to a navigational error.7 The accident is generally presented as the first very serious tanker disaster that attracted the attention of the general public, including on the level of methods for mitigating the spill, and the risks related to the use of dispersants. As already mentioned, this catastrophic incident resulted in important regulatory developments on marine pollution prevention and compensation.

- The Amoco Cadiz accident (1978)

Built in 1974 and flying the Liberian flag, the Amoco Cadiz was laden with 223,000 tonnes of light crude oil and 4,000 tonnes of bunker fuel, when she encountered severe weather conditions and finally grounded off the coast of Brittany, France. The vessel was on her way from the Arabian Gulf to Europe. The accident happened on 16 March 1978, and was attributed to the failure of the vessel’s steering mechanism. The entire cargo was spilled into the sea, causing a most extensive pollution problem to Brittany coastline. Once again, the attention of the media and the public opinion was geared towards this maritime disaster with huge ecological consequences. The casualty had resulted in the largest loss of marine life ever recorded after an oil spill at the time. The incident gave rise to useful lessons learnt insights on cleanup and impact analysis.8

- The Exxon Valdez accident (National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration and Environmental Protection Agency, 1989)

The US-flagged single hulled oil tanker Exxon Valdez, which was built in 1985, grounded on Bligh Reef, Alaska, on 24 March 1989, leaving its footprint on maritime history on account of its magnitude, exceptionally high costs for clean-up and litigation, and salient impact on the adoption of new regulations.9

The oil tanker was loaded with 180,000 tonnes of crude oil. She was travelling outside normal shipping lanes in order to avoid ice when she struck Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound. The accident caused major environmental problems and impacted on the health, well-being and economy of the local society (fishing, etc.). It resulted in approximately 38,500 tonnes of oil pouring into the Prince William Sound, Alaska (US), affecting 1,700 km of coastline.

Some of the probable causes of the grounding, pointed out during the investigation of the accident, were the following: human failure on numerous levels (proper manoeuvre of the vessel, proper navigation watch, etc.) possibly due to fatigue and excessive workload; failure of the shipping company to supervise the master and provide a rested and sufficient crew for the vessel; vessel traffic system-related ...