eBook - ePub

Presidential Leadership and African Americans

"An American Dilemma" from Slavery to the White House

- 214 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Presidential Leadership and African Americans

"An American Dilemma" from Slavery to the White House

About this book

Presidential Leadership and African Americans examines the leadership styles of eight American presidents and shows how the decisions made by each affected the lives and opportunities of the nation's black citizens. Beginning with George Washington and concluding with the landmark election of Barack Obama, Goethals traces the evolving attitudes and morality that influenced the actions of each president on matters of race, and shows how their personal backgrounds as well as their individual historical, economic, and cultural contexts combined to shape their values, judgments, and decisions, and ultimately their leadership, regarding African Americans.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Presidential Leadership and African Americans by George R. Goethals in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicologia & Storia e teoria della psicologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

George Washington

In the year 1728, William Byrd II, founder of Richmond, Virginia, participated in the mapping of the Virginia/North Carolina border. Based on his experience, he wrote the well-known History of the Dividing Line betwixt Virginia and North Carolina and then the Secret History of the Line.1 The latter offers a witty account of the mapping experience, as well as amusing and somewhat caustic views of North Carolinians. One anecdote recounts the fact that the surveyors ate corn pone, as that was the only food available. But when they offered some to a rather poor white Carolina native, the man “rode away without saying a word.” The problem, you see, is that corn pone was considered food for slaves. The man was insulted that his superior status was disregarded.

Over a quarter-millennium later, not much had changed. In 1968, a graduate student from Massachusetts at a North Carolina university asked his rural landlady if he could have some of the beet greens that she had discarded into the trash. She cheerfully agreed but walked away chortling that this Yankee rube was “fixin’ ” to eat “colored food.” However, while there are continuities across the centuries, by the late-1960s, race relations in the South and the United States as a whole had at least started to change. And they have arguably changed more in the past forty years than in the previous 300.

In 2008, Americans elected an African American president. It’s hard to imagine when such a possibility first seemed more than fantasy. Certainly not in 1789, when George Washington was inaugurated as the first president of the United States. Not in the 1870s, when Ulysses S. Grant tried with limited success to combat the white South’s resistance to post-Civil War reconstruction. And not in the second decade of the twentieth century, when Woodrow Wilson segregated federal offices. And not in 1968. How did the country finally turn the page? There are many threads in this important tapestry of social change. One of them is the attitudes and actions of American presidents regarding African Americans. Some presidents pulled the thread forward. Others tried to unravel it. The story spans the entire history of the country and of the presidency. In fact, it begins well before the American presidency was invented in Philadelphia in 1787. Still, the attitudes and actions of the first president, George Washington, offer a good place to start.

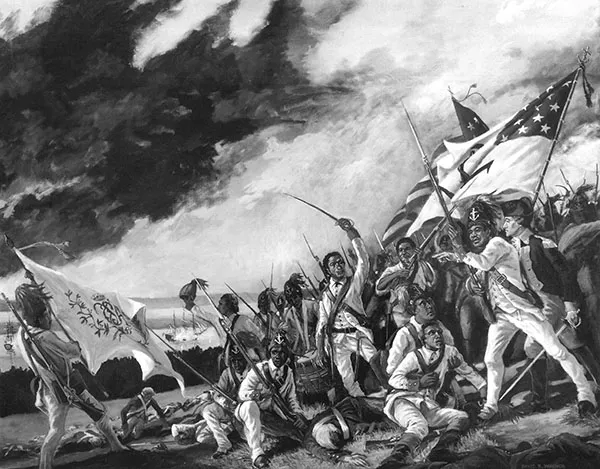

In October of 1781, more than six years after he had assumed the role of commander in chief of the Continental Army of the united British colonies, George Washington faced one of the most climactic leadership moments of his life. The large British army, led by Lord Cornwallis, was trapped on the Yorktown Peninsula in Virginia. A siege operation was tightening the noose around Cornwallis’s forces. However, a British fleet from New York was reportedly sailing to the rescue. Washington knew that two strongholds in the British line of defense, Redoubts 9 and 10 at Yorktown, had to be captured by assault before the ships arrived. Otherwise, a near stalemate would aid Cornwallis. Washington selected the best troops in the army to make a clandestine nighttime attack on the two redoubts. Redoubt 9 would be assaulted, silently, by French regiments. Redoubt 10 would be attacked by the best American units, under the command of Colonel Alexander Hamilton. One of the units in the vanguard of Hamilton’s forces was the First Rhode Island Regiment. A French officer called that regiment “the most neatly dressed, the best under arms, and the most precise in its maneuvers.”2

The attack on the redoubts was not only important; it was also dangerous. Before the battle, General Washington spoke to the attacking forces, who had been separated from the rest of the army, and underlined what hung in the balance. The revolution could succeed if the assaults that evening succeeded. But surprise was essential, and Washington ordered that no muskets were to be loaded, in case one should fire by accident and alert the defenders. The men were to attack with bayonets and engage in hand-to-hand combat. Strict silence must be observed. Orders were to be followed meticulously.

Washington’s gamble worked. On the evening of October 14, the French and American attackers surprised the British enough, and fought well enough, to prevail. The next day, Washington could hardly contain his elation. He visited the captured redoubts, even though he was in danger from English snipers. Two days later, Cornwallis signaled that he would surrender his army. At the formal surrender ceremony that followed, as its flags were furled, the British army bands played “The World Turned Upside Down.” For both sides, it truly had.

But, one more detail. The French officer who noted that the First Rhode Island Regiment was “the best under arms, and the most precise in its maneuvers” also noted that “three quarters of the Rhode Island regiment consists of negroes.”3 In some ways, this was unremarkable. By the end of the war, the Continental army was estimated to be about one quarter black. That blacks were a significant part of the army was simply taken for granted. However, this was far from true at the beginning of the war. When George Washington arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to take command of the army in July 1775—just days after the Battle of Bunker Hill but a year before the Declaration of Independence—he was shocked to see black soldiers. However, in the ensuing six years leading up to Yorktown, much had changed in the army and in George Washington’s thinking. The change for Washington during that period was in fact just one part of a much greater evolution in Washington’s outlook that started well before the war and ended well after it.

Figure 1.1 George Washington chose the mostly black First Rhode Island Regiment to carry out a crucial combat mission in the Battle of Yorktown.

David R. Wagner, “Desperate Valor, August 26, 1778, the 1st Rhode Island Regiment.” By permission of the artist.

The world into which George Washington was born during the winter of 1732 had been taking shape for over a century but had only stabilized a few decades before. England’s Jamestown colony in Virginia was begun in 1607, exactly a century and a quarter before Washington’s birth. Initially, the labor that kept the colony alive, though just barely, had been supplied by indentured servants. These were individuals, generally from the poorer classes in England’s highly stratified social structure, who agreed to work for a period of years, typically seven, before they were free to try to establish their own lives. They were white.

The characteristics of Virginia’s, and America’s, labor force and overall demographics began to change dramatically in 1619. In August of that year, a Dutch ship brought twenty captured Africans to Jamestown. It is likely that the Dutch crew took these captives by force from a Portuguese ship off the coast of southern Africa near what is now Angola. Arriving in Jamestown, the crew exchanged the twenty Africans with the English settlers for food. This was the start of the practice of bringing enslaved Africans to what is now the United States. By the time Congress outlawed the slave trade in 1808, somewhere between 400,000 and 500,000 African slaves had been brought to North American shores. However, this number represents only a small fraction of the number of Africans forced into slavery in the New World. Historian Eric Foner estimates that roughly 10 million of the 12.5 million people who came to the Western Hemisphere between 1500 and 1820 were African slaves.4 More than 90% of those slaves were taken to the Caribbean or South America, especially Brazil. Life expectancies for slaves working in the mines of Brazil and the sugar plantations of the Caribbean were much lower than life expectancies for slaves in the English colonies in North America. There were more women among the slaves in North America, the work was less brutal than in the sugar plantations, and slaves married and had children. As a result of natural increase, the population of enslaved African Americans in North America had reached roughly 600,000 by the time of Yorktown, with by far the greatest numbers in Virginia.

When Washington was born, approximately half of the population of Virginia were slaves. There were also significant numbers of free blacks. In the 1660s and 1670s, perhaps as many as one third of blacks in Virginia were free. They had gained their freedom in a number of different ways. Some of the first Africans brought to Virginia were treated the same as white indentured servants. They were given their independence after working for a number of years. Religious considerations also played a role. Some of the Africans brought to Jamestown by Dutch sailors had been baptized, probably by the Spanish. Settlers in Virginia initially did not feel that baptized Christians should be slaves. Laws passed in the late 1660s changed that. By then, economic considerations—the need for slave labor—trumped religion. But for a time, nonwhite Christians were excluded from slavery. In addition, some white Virginians freed their slaves or allowed them to buy their freedom.

One of the factors that added to the number of free blacks—or, more accurately, free mixed-race peoples—is that blacks and whites often intermarried. This was particularly true when white and black indentured servants worked side by side. In the mid- and late-1600s, the concept that people of different races should be categorically treated differently simply on the basis of color had not yet taken hold. At the same time that significant numbers of nonwhites gained freedom, the importation of African slaves declined. In the late 1600s, England was happy to ship poor white people to the Americas. There was no shortage of labor in the colonies.

In about 1700, the mother country began reversing its policy. It worried about a shrinking supply of cheap labor. As a result, fewer white indentured servants were available for planters in Virginia. Virginians made up the difference with African slaves.5 By the time George Washington was born, Virginia was steadily importing slaves. At the same time, views concerning both the mixing of races and the freeing of black slaves were hardening. Perhaps in the late 1600s, Virginians could imagine a society in which free blacks and whites participated collaboratively. By the time George Washington reached adulthood, that view had disappeared.

The increase in the number of slaves in Virginia during the eighteenth century is startling. There were roughly 10,000 in 1700, 30,000 in 1730, and 105,000 in 1750.6 The first United States Census, conducted in 1790, showed 293,000 slaves in Virginia, representing 39% of the total population of 748,000.7 At that time, Virginia was by far the most populous of the fifteen states (the thirteen original colonies plus Vermont and Kentucky), and it had by far the largest number of slaves. South Carolina was second in number of slaves with 107,000. While Virginia’s slave population was growing, it was actually declining as a percent of the population. For example, in 1760, thirty years before the first census, Virginia’s 120,000 slaves were 41% of the population, more than the 39% in the first US census. Like other North American British colonies, Virginia’s white population was also growing dramatically throughout the 1700s. In short, the British North America into which George Washington was born was a dynamic, fast-growing set of colonies with significant slave populations from Maryland to Georgia.

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732. His family enjoyed moderate wealth and status in colonial Virginia. His birthplace was on the shores of the Potomac River, about fifty miles south of present-day Washington, DC. George’s father, Augustine (Gus) Washington, owned some 10,000 acres of land and fifty slaves.8 Gus and his first wife had two sons, Lawrence and Austin. After their mother died in 1729, Gus married Mary Ball, who in turn became the mother of George and four younger siblings. The family moved several times around the area near Fredericksburg, Virginia, but life was otherwise stable and comfortable. George greatly admired his two half-brothers, older by fourteen and twelve years, respectively. Lawrence in particular was a dashing role model: Educated in England, he served in the British Army in North America and was elected to Virginia’s House of Burgesses.

Life changed drastically in 1743; George was eleven years old. His father, Augustine Washington, died at the age of forty-nine. In ten years’ time, when he reached twenty-one, George would inherit significant property, including ten slaves. But starting immediately, he only inherited heavy family responsibilities. His mother insisted that George help her with the property at their home called Ferry Farm, near Fredericksburg, and also serve as conscientious older brother. He was charged with being mindful of a sister one year his junior and brothers two, four, and six years younger. It amounted to George being captain of a rambunctious team. The young Washington always had a difficult relationship with his mother. She lived until he became president of the United States and frequently complained that he never did enough to take care of her, financially and emotionally. The burdensome eldest son role into which young George was thrust at age eleven was one that he never outgrew.

One reason George had to assume so much family responsibility was that his two older half-brothers, Lawrence and Austin, were grown men, both in their twenties, and had left home. Still, Lawrence watched over George from a distance as much as George cared for his younger siblings up close. It was through Lawrence that George became acquainted with the wealthy and powerful Fairfax clan at Belvoir, a large estate on the Potomac a day’s ride from Ferry Farm. Three months after Augustine Washington’s death, Lawrence had married Ann Fairfax, a daughter of Lord William Fairfax, owner of large tracts of land in the Virginia colony. As a young boy, George became attracted to his brother’s in-laws, and they to him. Lord Fairfax admired George’s casual masculinity and his exceptional riding ability. Fairfax was an ardent fox hunter, and George was able to impress through his way with horses and his talent in the chase. In his early teenage years, George also became a close friend of Lord Fairfax’s son George William Fairfax, seven years George’s senior. When Washington was sixteen, George William married the beautiful eighteen-year-old Sally Cary. Young George was smitten, and Sally at times reciprocated his discrete flirtations. Thus Washington began an intense but proper relationship with Sally Cary Fairfax that transfixed him for the rest of his life.

Due to his favored position in the Fairfax family, in 1748 sixteen-year-old George was included in a party to venture into the Shena...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations and Credits

- Series Editor Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction: Presidential Leadership and the American Dilemma: Psychological Dimensions

- 1 George Washington

- 2 Thomas Jefferson

- 3 Abraham Lincoln

- 4 Ulysses S. Grant

- 5 Theodore Roosevelt

- 6 Woodrow Wilson

- 7 Harry S. Truman

- 8 Lyndon B. Johnson

- Conclusion

- Index