Historical Background

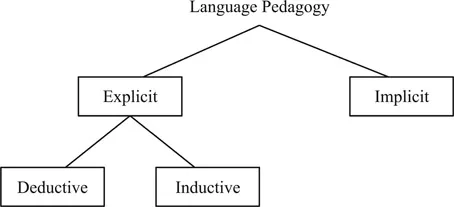

Grammar has long been a crucial part of language teaching. It has been both the organizing principle and the primary component in many methods, and it has been a minor or negligible component in other methods. Major issues in teaching grammar have been related to whether grammar should be taught explicitly (i.e., through rules) or implicitly (i.e., through meaningful input without recourse to rules), or whether it should be taught deductively (i.e., through rules which can be applied to produce language) or inductively (i.e., through examples of language use from which rules can be generalized).

In his history of language teaching, Kelly (1969) observed, “where grammar was approached through logic [i.e., deductively], the range of methods was reduced to teaching rules; but where inductive approaches were used, the deductive did not necessarily disappear” (p. 59). For Kelly, the teaching of grammar appears to be explicit. However, some current approaches and some second language (L2) research behoove us to consider implicit as well as explicit approaches. An initial taxonomy of approaches to teaching grammar can be represented as in Figure 1.1.

When classical Greek and Latin were the most important second or foreign languages, getting learners to use one or both of these languages fluently was the primary objective. Well-to-do families had their children tutored by proficient users of these languages, who probably used both implicit and explicit methods, all without the aid of textbooks. The tutors undoubtedly had access to a number of manuscripts to use for reading instruction and as models for writing. Kelly (1969) notes that the learners were often speakers of either Greek or Latin and were learning the other major language as part of their education.

FIGURE 1.1 Taxonomy of approaches to teaching grammar

During the Middle Ages, the formal aspects of Latin were the focus of teaching to speakers of various European vernaculars. Rote memorization of grammar rules (i.e., morphology [inflectional affixes] and syntax [word order]) was the primary teaching method.

The Renaissance saw the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg in 1440, which permitted the subsequent mass production of books, including not only the Bible and religious materials but also textbooks. According to Kelly (1969), Renaissance-era teachers of Latin tried to supplement the formal rigidity of medieval methods by introducing mnemonic devices (e.g., for declensions, the case-based inflections on nouns and adjectives) and by encouraging learning via analogy (i.e., applying previously learned rules and paradigms to new contexts). The Renaissance culminated in an eventual refocusing of effort on the learner’s ability to use the foreign language being studied.

One of the famous early post-Renaissance language methodologists was Jan Amos Comenius, a Czech scholar and teacher, who published materials about his language teaching techniques between 1631 and 1658 (Kelly, 1969). Some of the implicit techniques that Comenius proposed were the following:

- use imitation instead of rules to teach a language;

- have your students repeat after you;

- help your students practice reading and writing; and

- teach language through pictures to make it meaningful.

In contrast, the followers of the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes (1596–1650), whose influence continued through the 18th century, returned wholeheartedly to grammatical analysis and deductive learning in language instruction. They began with the grammar of the learner’s first language (in this case French) and then taught the grammar of Latin. Language instruction consisted of the manipulation of units and rules, and the objective was to develop the ability to parse words and sentences. The French Port Royal grammars, which were heavily influenced by Descartes’s work, taught grammar rules through the memorization of verse (Kelly, 1969).

This return to the association of grammar with logic and mathematics paved the way for the highly analytical and purely deductive grammar-translation approach to language teaching. It later became codified in Europe, most especially in the work of Karl Ploetz (1819–1881), a German scholar who had a great influence on the language teaching profession of his time and for years thereafter. Prator (1974) summarizes Ploetz’s grammar-translation method as follows:

- the medium of instruction is the students’ L1 (first language);

- there is little or no use of the L2 for communication;

- the focus is on grammatical parsing (forms and inflections of words);

- there is early reading of difficult texts;

- a typical exercise is to translate sentences from L2 to L1 (or vice versa); and

- the teacher does not have to speak the L2 fluently (but just needs to know the grammar).

Not surprisingly, the result of this method was (and is) an inability to use the L2 for communication!

As a challenge to the grammar-translation method, the late 19th and early 20th century saw the development of “natural” or direct approaches to language teaching, which were implicit and inductive in nature. Both the Direct Method and the Reform Movement contributed to this change in focus from language analysis to language use. The Reform Movement pioneers were members of the International Phonetics Association (IPA), founded in 1886, and they argued mainly for a scientific approach to the teaching of oral skills and pronunciation. At about the same time, Francois Gouin began to publish his work on the Direct Method in 1880. It became popular in France (Gouin’s country) and Germany. Key features of the Direct Method, according to Prator (1974), are the following:

- there is no use of the learners’ L1 (the teacher need not be fluent in the learners’ L1);

- the teacher must have native or near-native proficiency in the target language (the L2);

- lessons consist of dialogues and anecdotes in conversational style;

- actions and pictures make meanings clear;

- grammar is learned primarily implicitly (occasionally inductively);

- literary texts are read for pleasure (not grammatical analysis); and

- the target culture is also taught (via implicit and inductive techniques).

In the early 20th century Émile de Sauzé, a disciple of Gouin, brought the Direct Method to Cleveland, Ohio, in the United States to introduce it in the public schools. He had only partial success due to the lack of native or near-native speakers of Spanish, French, and German to serve as teachers who could correctly model and implement the Direct Method (Prator, 1974).

Grammar in 20th- and 21st-Century Approaches

Howatt (2004) contends that the Reform Movement of the late 19th century, which was briefly mentioned above, played a role in the simultaneous development of both the Audiolingual Approach in the United States and the Oral-Situational Approach in the United Kingdom. Of these two, this chapter will focus mainly on the Audiolingual Approach because of its dominance in the United States from the mid-1940s through the early 1970s. The Audiolingual Approach is based on the principles of structural linguistics (Bloomfield, 1933) and behavioral psychology (Skinner, 1957). Audiolingualism’s most important characteristics include the following (Prator, 1974):

- mimicry and memorization are used as techniques, based on the belief that language learning is habit formation;

- grammatical structures are sequenced, and rules are taught inductively through planned exposure;

- skills are sequenced (first listening and then speaking with reading and writing postponed);

- efforts are made to ensure accuracy and prevent learner errors so that bad habits are not formed;

- language is often manipulated without regard to meaning; and

- learning activities and materials are carefully controlled.

A growing dissatisfaction with the mechanical aspects of audiolingualism led to several challenges. First, from the perspective of cognitive psychology (Neisser, 1967) and Chomsky’s (1959, 1965) model of grammar, language learning came to be viewed not as habit formation but as the acquisition of recursive rules that can be extended and applied to new circumstances as needed. This early cognitive approach argued that language acquisition involves learning a system of infinitely extendable rules based on meaningful exposure with hypothesis testing and rule inferencing (inductive learning) driving the acquisition process. Errors are seen as inevitable, something teachers can use for feedback and correction (deductive strategies). It was concluded that grammar should be taught both inductively and deductively because some students learn better one way than the other.

Another challenge to the Audiolingual Approach came from the Comprehension-based Approaches put forward by Postovsky (1974), Winitz (1981), Krashen and Terrell (1983), and Asher (1996). The best known among these is the Natural Approach by Krashen and Terrell; however, all of these authors propose that listening comprehension is the most important initial skill to master in a second language. They also believe that there should be an initial silent period where learners experience rich, meaningful input. During this initial period, learners can signal their comprehension by using gestures or actions, choosing objects or pictures, or uttering minimal verbal responses. Learners should not be forced to speak before they feel ready to do so. Overt error correction is seen as unproductive and not important as long as learners can understand and make themselves understood. Rule learning is minimized and used only to help more advanced learners monitor or become aware of their performance in speech or writing. Thus, the teaching of grammar is largely implicit in these comprehension-based approaches.

The most radical challenge to audiolingualism, however, has come from the Communicative Approach (Duff, 2014), which is an outgrowth of research in linguistic anthropology in the United States (Hymes, 1971) and Firthian Linguistics in the United Kingdom (Firth, 1975), with Halliday (1973, 1978) being the most notable disciple of Firth. These scholars view language as a meaning-based system of communication, not an abstract structural conceptualization. In fact, it was Hymes (1971) who created the term communicative competence to complement Chomsky’s (1959, 1965) linguistic competence. Language methodologists followed suit. Communicative approaches reasoned that because most L2 students are learning a language for purposes of communication, the content of a communicative language course should be organized around semantic notions and social functions (Wilkins, 1976) and not around linguistic structures or grammar. In communicative approaches, notions and functions are viewed as being as important as grammar (if not more so). Beginning in the mid-1970s and up to the present day, various incarnations of the Communicative Approach have appeared (e.g., immersion education, content-based language teaching, English for specific purposes [ESP], task-based language teaching, discourse-based language teaching, corpus-based language teaching, and so on). What all of these incarnations share is a focus on language use and the ability to deploy language resources and skills for purposes of communication, along with other objectives such as learning subject matter, acquiring academic language proficiency, or acquiring professional, vocational, or sociocultural skills. While students learning a language through these approaches generally acquire good comprehension skills and fluency in using the L2 for communication, it was gradually noticed that many such learners did not acquire accurate use of L2 morphology and syntax as an automatic by-product (Swain, 1985). Thus began a search regarding how best to integrate the teaching of grammatical accuracy into communicative language teaching (CLT).