![]()

1

PEOPLE AND PRODUCTS IN AN EVOLVING MARKETPLACE

By the end of this chapter, you will:

• appreciate the centrality of possessions in everyday life;

• understand the role of product possessions in creating a self-identity;

• gain insight into the nature of materialism, material and virtual possession attachments, and consumer/brand relationships;

• recognize the role of material artifacts from cultural and historical perspectives.

In contemporary times, the buying and having of material goods, along with a growing array of services, have become as central to people’s sense of being as family and career. “I shop, therefore I am, and I am what I consume” may well be the defining dictum of modern woman and man. Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, commercial selling and buying behavior have represented activities that essentially define successive generations, as fully interwoven within the fabric of industrialized nations as technological, scientific, social, and political developments. Whether it be the clothes we wear, the homes and communities where we reside, the types of pets we own, or the color of the earbud headset through which we privately listen to our preferred musicians as we wend our way through public settings, our consumption choices are inseparable from who we are to ourselves and to others.

Individuals and societies are inevitably shaped—and in some cases, transformed—by the products and services they create and utilize. Consider, for example, mid-twentieth-century scenes of families huddled around radios and televisions, images that are as firmly etched in our collective memories as Norman Rockwell paintings, illustrating how these early forms of broadcast media brought intimacy to the consumption of information and entertainment as unified experience within the family unit. Fast forward to the early years of the current millennium (the so-called “marketing 2.0 era”) to recognize how the widespread adoption and use of electronic and mobile devices have rendered “intimacy” to the level of absurdity, as the Internet and its social networking offspring enable countless multitudes to connect through public revelations of personal thoughts and behaviors in 140 characters or less. We now nestle in front of the television in the bosom of our family while plugged into social networks, a phenomenon that has come to be referred to as “connected cocooning.”1 We choose our friends and lovers on the basis of the books they read, the music they listen to, the celebrities they idolize, their preferences in foods and restaurants, and their Facebook “likes.” “We just didn’t have much in common anymore” could sound the death knell of a relationship on grounds of incompatibility as much in the sense of “He’s a Mac, she’s a PC” as due to a divergence in lifestyles and values.

Consumers and products: Can there be one without the other?

The expression “iPod, therefore I am” signifies that in the contemporary era people and products have begun to merge, both literally and figuratively, and that it is nearly impossible to think of one without the other. This singularity between people and products suggests both the positive and dark sides of consumption (see Box 1.1).

BOX 1.1 THE SINGULARITY IS NEAR

Renowned inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil envisions a remarkable future—one in which the rapidly expanding rate of technological change will have profound transformative effects on human life, enabling people to transcend their biological limitations and amplify their intelligence and creativity. This staggering vision reflects what Kurzweil refers to as the “singularity,” a shortened version of the term “technological singularity” that originally referred to the arrival of machine superintelligence, beyond which our ability to predict the future breaks down. For Kurzweil, singularity refers to a penultimate evolutionary epoch that will follow the merging of human technology with human intelligence.

Kurzweil’s predictions are based on the premise that technological change is exponential rather than linear (a point that we examine in greater detail in subsequent chapters), as progress in any one area feeds upon itself as well as accelerating progress in other fields:

what would 1,000 scientists, each 1,000 times more intelligent than human scientists today, and each operating 1,000 times faster that contemporary humans (because the information processing in their primarily nonbiological brains is faster) accomplish? One chronological year would be like a millennium for them… an hour would result in a century of progress (in today’s terms).2

As nonbiological intelligence eventually comes to predominate, the nature of human life will undergo radical alterations in terms of how people learn, play, wage war, and cope with aging and death. As elaborated in his best-selling 2006 book The Singularity is Near, the predicted union of human and machine presents both opportunities and threats to the human race:

In this new world, there will be no clear distinction between human and machine, real reality and virtual reality. We will be able to assume different bodies and take on a range of personae at will. In practical terms, human aging and illness will be reversed; pollution will be stopped; world hunger and poverty will be solved. Nanotechnology will make it possible to create virtually any physical product using inexpensive information processes and will ultimately turn even death into a soluble problem.3

The social and philosophical ramifications of these changes would be profound and, according to Kurzweil’s detractors, the threats they pose are considerable. Others, however, view Kurzweil’s ideas as a radically optimistic view of the future course of human development.

If it is true that we are what we consume, then it is not a stretch to say that consumption is central to what it means to be human. Further insight into what it means to be a consumer can be gleaned through a simple exercise by reflecting on what it is that one typically consumes during a typical day. Part of the answer, of course, is readily apparent through a consideration of the basic sustenance required to live—food, water, air, protection from the elements, and the like. In this sense, people consume to survive by striving to satisfy physiological (or “first-order”), unlearned needs. But we also regularly consume personal hygiene products like soap, toothpaste, hair shampoo, perfume; services such as electricity, heating, Internet service, mass transportation, and phone service; the ink and lead of writing implements we employ; ATM machines; electronic goods and services, including DVDs, online streams, radio and television; clothing; and health care items, such as headache remedies, birth control pills, cough syrup, massages, and the advice of doctors and pharmacists. We also consume various forms of entertainment, be it live (e.g., buskers on the street corner or in the subway; an opera performance or theater play; a football match) or recorded (a new Star Trek movie or Yo la Tengo CD).

Our brief exercise would not be complete without a recognition of the wealth of information and ideas we acquire and consume daily from the press, books, classroom lectures, podcasts, the Internet, computer tablet or smartphone, as well as the many intangibles we are apt to absorb only at an unconscious level, such as freedom and democracy, history, spiritual traditions, architecture, and art. As Richard Saul Wurman pointedly observed in his 1989 book Information Anxiety, “a weekday edition of The New York Times contains more information than the average person was likely to come across in a lifetime in seventeenth-century England,”4 suggesting the dramatic expansion of information consumption in the contemporary era. These various forms of consumption satisfy needs that are less linked to basic survival than they are to more unlearned, psychological motives. In common parlance in the field of marketing, each of these listed objects of consumption, whether basic or learned, can be considered to be a product, defined as “anything that can be offered to a market that might satisfy a want or need”5—a definition that I have adopted for this book. This admittedly broad definition encompasses the full gamut of consumables, including physical goods (Panasonic microwave oven; Dyson vacuum cleaner), services (pizza delivery, tax preparation), persons (Beyoncé, David Beckham), places (Disneyland, the Paris Opera, Hawaii), organizations (Greenpeace, Médecins Sans Frontières), and ideas (safe sexual conduct, drinking and driving, religion).

The recognition of the broad array of consumption objects also helps us recognize the breadth of consumer behavior. At one time, this term was narrowly conceptualized as roughly synonymous with buying behavior. Marketers focused on the exchange process involving shoppers and retailers, with consumers paying to acquire desirable, needed goods and services typically produced by manufacturers and service providers and offered by third parties in stores or other business settings. As the complexity of consumer decision making took front and center among the concerns of consumer researchers and practitioners,6 so too did the meaning of consumer behavior, which now encompasses the full range of the consumer decision-making process, beginning with the decision to consume (to spend or save, to have or not to have) and ending with product usage, disposition, and post-purchase reflections (e.g., “Am I satisfied with the purchase?”; “When shall I buy a new one?”).

In a broader sense, consumer behavior also concerns processes related to having (or not having) and the ultimate state of being derived from the consumption process.7 This is to say that a comprehensive understanding of consumer behavior requires a consideration of how the possession and use of consumption objects influences who we are, how we perceive ourselves and others, and how these objects impact the broader social and cultural worlds we inhabit in our various roles as citizens, parents, professionals, and so on. In the remainder of this chapter, I address these considerations with a focus on areas of consumer psychology (micro-level) and culture (macro-level) that are intricately linked to consumers’ engagement with products, including a consideration of materialism, self-identity, consumer/brand relationships, and cultural artifacts.

Engagement in the material world: From “consumer” to “prosumer”

“Engagement” is a concept that is redefining contemporary marketing. From the marketer’s perspective, the new challenges of greater consumer connectedness via social networking and online communities have harkened the call for marketing strategies that engage potential customers in collaborative relationships with compelling content and force a rethinking of the traditional means by which marketers attempted to communicate with and influence customer targets. The traditional “top-down” marketing paradigm (business-to-consumer marketing, or B-to-C) whereby consumers were content to select goods produced, distributed, and promoted by companies and advertisers which decided what customers needed and desired has been turned on its head in an amazingly short span of time. In its place are bottom-up, grass-roots approaches (consumer-to-consumer marketing, or C-to-C) that are shaping the business world in ways unimagined only a few decades ago. Consumers are increasingly taking control of the marketplace and are no longer merely passive participants in the wide array of activities that comprise the marketing enterprise. Whether it be the creation or modification of products, the establishment of prices, the availability of goods, or the ways in which company offerings are communicated, consumers have begun to take a more active role in each of the various marketing functions.

These developments have led some to call for a shift in nomenclature that replaces the term “consumer” with “prosumer,” the latter of which is believed to better reflect how people have become more proactive and engaged in all facets of the consumption process. The prosuming notion—based on a combination of “producer” and “consumer”—dates back to pre-Internet 1980, when futurist Alvin Toffler envisioned a time when ordinary consumers would themselves become collaborative producers, actively improving or designing marketplace offerings.8

In Toffler’s prescient vision, the production of goods and services within the marketplace, where people produce for trade or exchange (“Sector B”), would ultimately be displaced or substituted by those produced by ordinary people for themselves or for their families (“Sector A”). As an example, Toffler noted the Bradley GT kit, offered at the time by Bradley Automotive, which enabled customers to design their own luxury sports car using partly preassembled components, including a fiberglass body, Volkswagen chassis, electrical wires, and plug-in seats. The Bradley GT kit anticipated BMW’s strategy prior to a new product launch of setting up an interactive website for users to design their own dream roadster. BMW automatically uploaded this information into a database and, based on data the company had already collected from loyal buyers, determined the most potentially profitable designs to put into production. This strategy was a precursor to BMW’s Virtual Innovation Agency, an online collaboration between external innovation sources and developers from the BMW Group. BMW receives an average of 800 ideas, concepts, and patents annually from sources ranging from individual consumers to research institutes and other companies. The BMW Group directly puts into practice about 3% of the submissions in product design and service. This and other “crowd-sourcing” projects, such as those implemented by Dell, LEGO, and Starbucks, are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5.

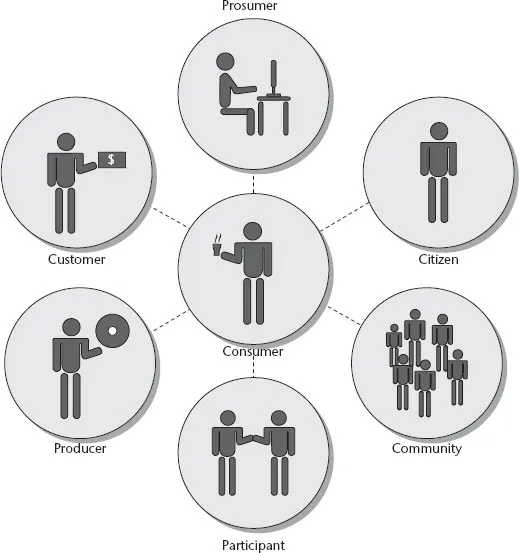

Just as the meaning of consumer behavior has broadened in recent decades, so too has our conceptualization of what it means to be a consumer. The changing nature of the modern consumer is depicted in Figure 1.1, as conceptualized by David Armano, social media blogger and managing director of Edelman Digital Chicago.9

FIGURE 1.1 The changing faces of the twenty-first-century consumer

Source: David Armano.

In Armano’s depiction, we see that consumers are no longer considered merely as customers or passive recipients of marketing content and offers, but as active and participative contributors to the marketing enterprise who ...