Corporate Entrepreneurship being a complex and ambiguous concept, our learning journey starts with the exploration of the various forms it takes in business organisations and in the literature. This first part includes:

First, though, what exactly is Corporate Entrepreneurship? We define the term as the process by which teams within an established company conceive, foster, launch and manage a new business that is distinct from the parent company but leverages the parent’s assets, market position, capabilities or other resources.

(Wolcott and Lippitz, 2007a)2

Introduction

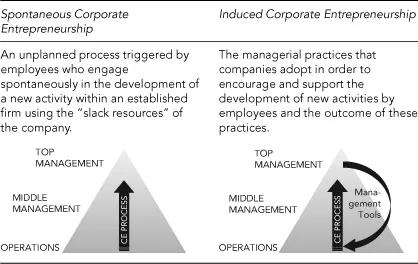

As these definitions suggest, Corporate Entrepreneurship refers to the development of new businesses within established firms. It involves internal teams and leverages internal resources. We will see later that Corporate Entrepreneurship is indeed broader and more complex but this first definition is sufficient to initiate our exploration. In this overview, we will see that Corporate Entrepreneurship can be either a spontaneous or management-induced process (see Figure 1.1). We will then describe its benefits, explore its relation to innovation and, finally, review some recurrent issues tied to its implementation.

Figure 1.1 Spontaneous versus Induced Corporate Entrepreneurship

The forthcoming chapters will refer to several of these cases contained in our extensive database (cf. Appendix 1).

Corporate Entrepreneurship as a spontaneous process

Well-established companies periodically benefit from the determination and talent of managers or employees who identify and seize business opportunities that were not envisioned by the top management team. According to Burgelman (1983MS), this phenomenon is inherent in the nature of large organisations. Large organisations have “organisational slack”; that is:

[A] cushion of actual or potential resources which allow them to adapt successfully to internal pressures for adjustment or to external pressures for change in policy, as well as to initiate changes in strategy with respect to the external environment.

(Cyert and March, 1963, p. 36)

Employees who have ideas can access these slack resources to explore and develop their project and some of them manage to do so successfully.

In a large firm, at any given point in time, there are normally several employees eager to pursue an initiative. As long as they have access to the resources they need, a number of them will manage to bring their project to completion, thus enlarging the scope of activities of the firm (Burgelman, 1983MS). We call this phenomenon “Spontaneous Corporate Entrepreneurship”. Spontaneous Corporate Entrepreneurship can be seen as a bottom-up process that complements the top-down strategic planning process and thus contributes to the strategic renewal of the firm.

Just as autonomous initiatives “spontaneously” emerge, the existing organisation – the “mainstream” to use Kanter and North’s terminology (1990) – “spontaneously” resists these initiatives and sometimes crushes them. This “mainstream”/“newstream” opposition has been described and analysed in a number of articles and business cases (cf. Burgelman, 1983MS; Hill, Kamprath and Conrad, 1992; Dougherty and Hardy, 1996; Hamel, 2000). The profound differences that characterise the part of the organisation that is involved in reproducing, administrating, optimising and controlling – the “mainstream” – to the part of the organisation that is involved in experimenting and creating – the “newstream” – leads to tensions, misunderstandings and even conflicts. Focus on short versus long-term results, attitude towards risk and acceptance of errors, respect of rules and procedures and reliance on informal networks are all dimensions on which the “mainstream” and the “newstream” radically diverge. The frictions these differences generate, amplified by turf wars, can lead to open or masked conflicts, which often end to the detriment of the weaker “newstream”.

What inspires “spontaneous” corporate entrepreneurs? They are, for the most part, guided by intrinsic motivations. Indeed, Corporate Entrepreneurship requires such efforts and involves such potential frustrations, that calculation is rarely the trigger. Two recurrent motivations stand out: first, corporate entrepreneurs believe that they act for the good of the company and that without their project the company would miss an opportunity; second, they are in search of greater autonomy, job satisfaction, self-affirmation and personal recognition. Clearly, these two motivations often coexist.

The motivations of corporate entrepreneurs are mostly intrinsic but this does not imply that they do not expect something in return: perhaps they want to manage the activity they have created, be promoted, get recognition, a bonus, a salary increase or a sabbatical. Initially, this remains a matter of conjecture, as corporate entrepreneurs seldom have clear expectations and almost never spell them out loud when they engage in a project.

Box 1.1 The MEMS Unit: a case of Spontaneous Corporate Entrepreneurship

The MEMS Unit (MMU) is an autonomous “entrepreneurial entity” created in January 2004 within the SBL group3 at the initiative of Eric D. Eric D. had the idea to commercially exploit the MEMS technology4 while he was Head of Research at a laboratory located in New England. He was turning 40 and looking for a new challenge. During his numerous discussions with senior management, Eric D. requested to have “carte blanche” as to the location of the activity and the choice of employees. He believed that his success strongly depended on the quality of engineers, technical partners and subcontractors with whom he would collaborate and he chose to return to France and reconnect with his former acquaintances. Thus was created the MMU, a new profit centre whose purpose was to develop and commercialise innovative technologies developed in the labs of the group: from its inception, it had the full support of the senior management of SBL keen to encourage innovation and promote entrepreneurial values.

Eric D. came back to France and found a site in the Paris suburbs and immediately put a clean room under construction. The material required for the manufacturing and testing of prototypes was purchased second-hand or recovered in other labs of the group. Eric D. surrounded himself with technically qualified and resourceful people able to face the many challenges and practical difficulties typical of the start-up phase of a business. He made sure everyone felt accountable by setting clear goals and reviewing them with his team regularly. Relationship management with the parent company was taken very seriously. The MMU, a tiny entity in terms of the SBL group, had to gain visibility while preserving its room for manoeuvre: targeted communication and internal networking were therefore strategic activities. Twenty-four months after its creation, the results of the MMU were very positive. Internal customers had approved two products and word of mouth began to take effect, opening new business prospects. The development speed of the MMU and the technical performance of its products, in spite of the entity’s limited means, surprised many inside SBL.

Source: Adapted from Bouchard (2009E).

As can be seen in this example, “spontaneous” corporate entrepreneurs can bring very tangible benefits to companies. If Corporate Entrepreneurship does contribute to growth and innovation, to strategic renewal even, should it not it be deliberately encouraged? Many companies answer this question with a yes and attempt to put in place tools and processes that aim at inducing Corporate Entrepreneurship.

Induced Corporate Entrepreneurship

Unlike spontaneous Corporate Entrepreneurship, induced Corporate Entrepreneurship is triggered by a combination of management actions and tools such as top management communication, ad hoc incentives and rewards, training programmes, project selection procedures and so on. Some employees, who might otherwise not have taken the plunge, will respond favourably to these actions and tools and decide to push forward – with the approval and support of the organisation – their own “entrepreneurial” project.

Over the last three decades, well-known companies such as the Xerox Corporation, Lucent Technologies, 3M or Gore in the United States and Schneider Electric, Siemens Nixdorf and Nestlé in Europe have devised and implemented their own combination of tools and actions to foster entrepreneurial initiatives. Several articles and case studies5 describe in detail what we will call “Corporate Entrepreneurship Devices” from now on; that is, an ad hoc combination of managerial and organisational tools designed and implemented by the management of established companies in order to induce Corporate Entrepreneurship.

Box 1.2 The Stockeasy project: a case of Induced Corporate Entrepreneurship

We are at the turn of the century and the French company Schneider Electric has reached a global leadership position in electrical equipment and industrial automation thanks to an ambitious strategy of mergers and acquisitions. These mergers and acquisitions, however, have dampened the internal growth dynamic of the company. Elaborated by the head of Strategy France, “A Myriad of Ideas” is a programme that aims at “revitalizing” the French business unit. At meetings held across the territory, the head of strategy preaches the good word to hundreds of managers, urging them to innovate and take initiatives. He promises that proposals, wherever they originated, will be evaluated and that the best will receive funding and support from a team of experts.

Jean-Marc R., a local manager, learned about “A Myriad of Ideas” during a presentation by a Strategy Department “evangelist”. He wholeheartedly embraced the philosophy of the programme, which corresponded to his personal vision of business and management: “From the beginning, I was interested in the process… And I immediately inserted four or five ideas in the database”. Among them, was the idea to create a business to manage local stocks of high turnover spare parts to better serve Schneider Electric’s clients. Jean-Marc’s idea was one of the first to be reviewed by the officials of “A Myriad of Ideas”. After discussing it with him, they encouraged Jean-Marc to refine his project and assess its feasibility. Jean-Marc was granted one day per week to work on the project and a budget of €24,000 to perform market research. The research produced encouraging results and the project was vetted for the next stage. But the important working capital requirements of the project scared Jean-Marc. Fortunately, a few months later, an enthusiastic colleague decided to join him, giving Jean-Marc extra confidence in his project. The project was approved by the Executive Committee of Schneider Electric who granted the two associates a budget of €760,000 and access the company’s venture funding scheme. The “Stockeasy” company was created: Schneider Electric owned 80 per cent of the shares and the two associates 10 per cent each. A few months later, the first spare parts were delivered to Schneider Electric’s clients. When asked about the whole process, Jean-Marc R. concluded with these words: “I was very lucky to be able to develop my business idea within Schneider Electric. I would not have managed on my own, but in this secure business environment, it’s been an amazing experience”.

Source: Adapted from Bouchard (2009IIC).

There are many ways to induce Corporate Entrepreneurship. The minimalist approach is characterised by its limited scope and ambition. In this approach, top management creates the conditions that will help the completion of specific projects, deemed par...