eBook - ePub

New Ghosts, Old Ghosts: Prisons and Labor Reform Camps in China

Prisons and Labor Reform Camps in China

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Ghosts, Old Ghosts: Prisons and Labor Reform Camps in China

Prisons and Labor Reform Camps in China

About this book

Much has been written about the laogai (sometimes likened to the Soviet gulag) in the People's Republic of China. Depending on the source, the prisons are described as nonexistent, enlightened institutions, or hellish places that subject the inmates to degradation and misery. The system is commonly thought of (by admirers and critics alike) as having a measurable impact on the national economy and providing significant resources to the state. Based on research in classified documents and extensive interviews with former prisoners, judicial personnel, and other insiders, and featuring case studies dealing with the three northwestern provinces, this book examines such assertions on the basis of the facts about this underexamined subject in order to arrive at a detailed, objective, and realistic picture of the situation. In the case of each province under study, the authors discuss the history of the provincial prison system and the impact that each has had at the macro, meso, and micro levels.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access New Ghosts, Old Ghosts: Prisons and Labor Reform Camps in China by James D. Seymour,Michael R Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

| “I feel entitled to say that neither labor camps nor concentration camps exist in China today [1954]. No one talks about them, whispers about them or even assumes that they exist.” |

Western journalist, after visiting China10

It has been said that a society can be judged by its prisons. Certainly many have judged China by its practice of incarceration. Thus, even though much has already been written about them,11 one hardly need justify offering a book about China’s “laogai” (labor reform systemA). It has been described as everything from non-existent (as in the above quotation) to enlightened institutions,12 to hellish places which subject the inmates to degradation and misery.13 The system is commonly thought (by admirer and critic alike) to have a substantial impact on China in general and on the national economy in particular.A

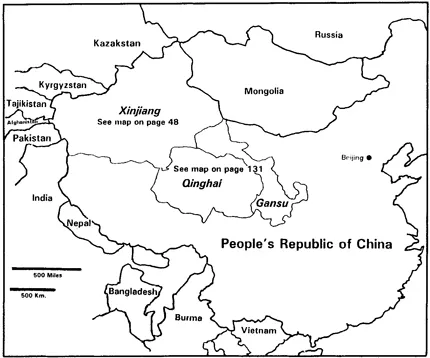

In this book we examine such assertions in the belief that in any human rights endeavor, the starting and ending point must be an objective evaluation of the real situation. The book will feature three case studies, namely the prison systems of China’s northwestern province-level units: Gansu, Qinghai, and Xinjiang. The first is predominately Han (ethnic Chinese), the others have large non-Han populations. In the case of each of these provinces, we will discuss the history of the provincial prison system, its size, and the economic impact that it has had at the macro, meso, and micro levels.

One of the more provocative recent studies on punishment in China has been written by Michael R. Dutton. His 1992 book Policing and Punishment in China is largely theoretical. “We must avoid … producing a simple narrative history of regulation and punishment.”14 Thus, Dutton, while far from apologizing for the laogai, believes that it is essentially what spokespersons for the Chinese authorities say it is, though he does put his own gloss on it all. He sees Chinese society in general as one big “factory” in which individuals comprise the raw material. Through work, they are turned into proper socialist citizens. The laogai is part of this system.

It is in the image of a factory, where education and production are joined as one, where life and labour are organized around the pole of productive collectivity, that laogai is set apart from the reformative schemes of the bourgeoisie. But the Chinese did not stop at the factory when deploying technologies of transformation. All the activities of the prisoners are structured into a social web designed to maximize transformation and policing. They are locked into relations which establish not only a disciplinary gaze but also a mechanism for transformation. It is the productivist image rather than that of inspection which dominates the Chinese prison.

All this is said to represent a fundamental break with China’s past.

It is in these terms that we can identify a radically different programme to that of disciplinary isolation and individuation. In the Chinese [Communist] programme, isolation gives way to mutuality, the individual to the group. What differentiates this form of collectivity from the classical form … is its dynamism.15

Dutton’s “gulag” includes not only the prisons and labor camps, but the entire system of social regimentation, including neighborhood registration. Parting ways with both Western liberals and Chinese reformers of recent decades, Dutton argues that what he calls the “gulag question” is to be understood as stemming fundamentally from neither lack of proper legal processes nor absence of respect for individual rights, but from China’s (and Chinese communism’s) Utopian bent.

Some may object to this equating of Gulag and Utopia. After all, Utopian schemes exist outside socialism. However, nowhere else is there the specific question of the Gulag. Within socialism, “the gulag question” has long since gone beyond the confines of discussion about problems of the prison. We would suggest that this is largely because it is only under socialism that such a well-developed vision of planned and organized social transformation goes beyond the confines of the prison. The collective and disciplinary model used to order and transform the criminal is also of use on the other side of the prison wall, and its transfer could aid in the transition process.16

Because China is supposedly evolving toward communism, “the transitional process must always take precedence over individual rights.”17 After we examine the laogai itself we shall consider Dutton’s impressions.

Why the Northwest?

How, one may well ask, can we justify concentrating on the prisons of one particular underpopulatedA corner of China? After all, the country’s largest prisons, such as the vast Shayang network of prison farms,B are in the east. There are a number of reasons we have chosen to concentrate on the northwest. It would not be feasible to do a thorough analysis of China’s prison system as a whole. It is too large a subject, and we simply do not have access to information about every province. On the other hand, due to some fortuitous accidents we have been able to learn about the prisons of these three provinces — which laogai regulations have sometimes treated as a group unto themselves.18 But should we have limited ourselves to this area simply because that is what we have data on? We think the focus is appropriate.

First of all, the northwest has an international reputation as the land of China’s “gulag.” Within China as well, “Qinghai Province” is a symbol for what can happen to perceived social misfits. Many a teacher has given independent-minded students the half-joking warning that if they failed to perform (or conform), they might find themselves in Qinghai — a metaphor for the whole laogai system. We believe that it is important to discern to what extent such reputations were, and are, justified.

We will begin with Gansu, partly because it was thE first northwestern province the Communists occupied, but more importantly because of the three provincial prison systems, Gansu’s is the most similar to the rest of China, and thus offers a good baseline against which the other two provinces can be measured. Because of Gansu’s typicality, the chapter can be considered a general overview of the Chinese prison system, and we include such data as the percentage of the population sentenced and imprisoned each year, and the role of shorter-term detention centers. Gansu, from Beijing’s point of view, is relatively non-sensitive, and therefore there is an abundance of information openly available. As for Xinjiang, there is no doubt that its prison system is unique, widely misunderstood, and of intrinsic interest. Here our focus is slightly different; we deal with the labyrinthine structure of the system and the conditions in the various prisons. We might have expected that the laogai systems in Qinghai and Xinjiang would have developed along the same lines, but for reasons we shall explain, the provincial authorities took quite different tacks, and in the end Xinjiang’s and Qinghai’s prison systems were like two ships passing in the night — in opposite directions. In the Qinghai chapter we analyze why its laogai has developed over the decades in the remarkable way that it has.

The fact that the three systems developed so differently tells us something about China: that, whatever the center may wish, the result is far from a homogeneous polity. We will also assess the relationship within the prison system in the context of the very different levels of development of the provinces: Xinjiang now being above average (in terms of per capita gross domestic product), Qinghai being about four-fifths the national average, and Gansu weighing in at only half the average.19 Thus, not even Gansu can be seen as a perfect microcosm of China’s prison system. Still, we feel that by becoming familiar with these three systems, one is in a position to understand the larger reality.

There are some subjects which we examine for all three provinces. For example, in each case, we endeavor to ascertain the size of the prison population, and also to evaluate the quality of life in the prisons. But sometimes a single provincial chapter will explore special topics, such as (in the case of Qinghai) the problem of drugs, and the role of the inspectorate. Of course, such subjects are relevant to more than just the one province where we study them, but in such instances we generally limit ourselves to the province where we have the most complete information.

This is a strictly empirical study. We are not particularly concerned with the theory of incarceration, or advancing social science. Certainly we have been determined to avoid ideological considerations and to be guided solely by the facts, allowing them to lead us wherever they would. Sometimes what we found surprised us, and our findings may even be upsetting to some. We seek not to please or offend, but to inform and to set the record straight. Thus, we have searched far and wide for the facts, and used multiple modes of analysis to cross-check our findings. We have used a variety of sources, including interviews with former prisoners, published sources, and secret documents. Regretfully, because the latter are often printed in very small quantities (sometimes as few as five — making it fairly easy to trace leaks), we have sometimes had to refrain from citing our sources. Nonetheless, we trust that readers will appreciate how carefully we have researched this book and how critically we have treated all information that has come our way; and that you will be willing to make the leap of faith on those occasions where a source citation would normally be called for.

That is not to say that the book is guaranteed free of error. This is a subject about which there is much unreliable information, both from official PRC sources and from the regime’s more political critics. The latter we largely ignore, preferring to do our own research. The former we deal with as best we can. Often, official disinformation can be spotted because of its internal inconsistencies, but even when this is not the case, we do not take official information at face value and have relied on the various means at our disposal to check it. The problem greater than misinformation is lack of information. Any subject so shrouded in secrecy is difficult to fathom, and it is possible that here and there we have made incorrect inferences from inadequate data. Although we regret any errors of fact or interpretation that we may have made, we are confident that our larger findings will stand the test of time.

Because nearly all inmates of the prisons examined in this book are men, we will use male pronouns. We estimate that nationwide about two percent of prisoners are women. In the 1950s, many prostitutes from cities like Shanghai were sent to the northwest (their situation generally put them in the gray area between prisoner and non-prisoner). Today, women prisoners in Gansu and Qinghai probably approximate the national average in number. However, inasmuch as only men are sent to Xinjiang from the east, the percentage is even smaller there.20

This book contains more facts and figures than a work of this sort would normally have. We have various reasons for what may seem as overkill, including the need for absolute clarity in view of the criticism we expect from all sides. When you begin to feel numbed by it all, dear reader, please bear in mind that each newly revealed fact is a blow struck for open inquiry. Each little revelation represents the uncovering of something China’s rulers have desperately sought to keep secret, ostensibly from the outside world, but really from the Chinese people. We hope this book will demonstrate the folly of closed government: it cannot be accomplished, and it serves no good purpose.

Incarceration in China is widely viewed as “special,” or different from the phenomenon as practiced in other countries. There is no general agreement concerning just what makes it different. Communist writers see the system of labor reform as a uniquely beneficent and constructive process, which results in the rehab...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables, Charts, and Maps

- Terminology and Prison Structure

- Foreword

- Preface

- Prologue: Visiting the Xining Laogai Area

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Gansu

- 3. Xinjiang: One Region, Two Systems

- 4. Qinghai

- 5. Prisons and Human Rights

- 6. The Aftermath: What Happens upon Release?

- 7. Conclusion

- Appendix 1: Author's Commentaries

- Appendix 2: Others' Commentaries

- Appendix 3: Laogai Regulations

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index