![]() Part 1

Part 1

Forgotten spaces![]()

1

School Buildings

‘A safe haven, not a prison …’

The Education Guardian, when it reported the results of the competition, ‘The School I’d Like’ summarised the statements made by children and young people as ‘The Children’s Manifesto’ (Birkett, The Education Guardian, 5 June, 2002).

The School We’d Like is:

A beautiful school

A comfortable school

A safe school

A listening school

A flexible school

A relevant school

A respectful school

A school without walls

A school for everybody.

The school building, the landscape of the school, the spaces and places within, the décor, furnishing and features have been called ‘the third teacher’ (Edwards, Gandini and Forman, 1998). A beautiful, comfortable, safe and inclusive environment has, throughout the history of school architecture, generally been compromised by more pressing concerns, usually associated with cost and discipline. The material history of schooling, as conveyed in school buildings, is evident still in the villages, towns and cities of any nation. In the UK, one need not look far to locate, still functioning as schools, stone-built ‘voluntary’ schools of the mid-nineteenth century. The ‘Board’ schools of the late nineteenth century still stand, as red brick emblems of the cities in which they were built in an era which placed enormous faith in ‘direct works’ and ‘municipalisation’. The schools built in the 1920s and 1930s reflected changes in educational policy indicating the beginning of a recognition of the diverse needs of children and consideration of health and hygiene. These decades saw the building of looser groupings of units, classrooms with larger windows and with removable walls being capable of being thrown almost entirely open. Architects worked to precise standards of lighting and ventilation as set out by the Ministry of Education. The post-war building plans saw the erection of buildings utilising modern prefabricated materials. Schools were built in large numbers, quickly and cheaply with the view that they would provide a stop gap until greater resources were available. ‘Finger plan’ schools, featuring one-storey classrooms set in parallel rows with a wide corridor to one side were popular. Thus started, for children, the long journey to toilets, hall and dining room as the buildings sprawled over large plots.

Already in the late 1960s, it was estimated that nearly three-quarters-of-a-million primary school children in England were being educated in schools of which the main buildings were built before 1875 (Department of Education and Science, 1967: 389). Standards were poor in general but there were particular problems, such as the 65 per cent of schools whose toilets were located in school playgrounds. The Plowden committee reported, ‘children have to use cold, dark and sometimes even insanitary school lavatories’ and remarked, ‘we have heard from many sources of the dislike of school that can be created by the condition of the school lavatories’ (ibid.: 391).

The new buildings erected in the 1960s and 1970s were needed to accommodate the swelling numbers on the school roll, the adoption of comprehensive secondary education and the extension of the school leaving age after 1973. Architects often used prefabricated assembly systems to help reduce costs and apart from some exceptional environments designed to be child centred, most new schools tended to resemble factories in their construction and style. Design aesthetics and comfort were usually given less importance than economy. However, many of the ideas about the flexible use of school buildings, first voiced by Henry Morris in the inter-war years, were revisited during this period. It was argued:

Society is no longer prepared to make available a set of valuable buildings and resources for the exclusive use of a small, arbitrarily defined sector of the community, to be used seven hours a day for two-thirds of the year. School buildings have to be regarded therefore as a resource for the total community available to many different groups, used for many different purposes and open if necessary twenty four hours a day.

(Michael Hacker of the Architect and Buildings Branch, Ministry of Education, cited in Saint, 1987: 196)

Open-plan arrangements reflecting child-centred pedagogy were criticised during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Educational policy under successive Conservative governments emphasised the importance of traditional methods of instruction and whole-class teaching rather than group collaboration and teacher facilitation. A research study of classroom arrangements in the UK suggests, however, that for the majority, tradition overcame fashion (Comber and Wall, 2001: 100).

After decades of having to meet the enormous costs of refurbishment and repairs, the UK government in 1992 adopted the policy of financing public services including the building and refurbishment of schools via the public–private finance initiative (PFI). The first privately financed state primary school was opened in Hull in January 1999. The 20 year Building Schools for the Future (BSF) capital programme, launched in 2004, aimed to transform education through the rebuilding of secondary schools throughout England and Wales. There was a similar initiative in Scotland. This was followed in 2007 by a three-year primary capital programme. So through a mixture of private and public investment, a large number of schools across the country were replaced stimulating a national debate about the significance of the built environment in transforming education. The views of pupils were considered important in the design process as the contracts were awarded to firms who demonstrated their capacity to engage with school communities. However, how this was achieved varied as subsequent research revealed (Parnell, 2010).

BSF was an ambitious programme intending to transform educational environments through vast investment. Like the pupils who commented on the importance of the built environment, the New Labour government was convinced of the critical role that design played in enhancing the learning experience. Some excellent buildings were produced in the process such as the first BSF school to open in London, Michael Tippett Special Educational Needs school in Lambeth. However, the standards and quality of other buildings have been criticised and the programme was closed down by the incoming coalition government in 2010.

The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) was established in 1999 by the New Labour government to oversee the quality of new capital programmes including school building renewal. CABE was very active in establishing design standards and warned that there was insufficient effort being made to consult the users of school buildings. ‘Schools need to get involved in that process and be specific about what they need. The whole process has got to be led by the curriculum’ (Fraser, CABE, The Education Guardian, 30 September 2002). However, CABE did not advise that children and young people should be involved in the design process. The Coalition government abolished CABE in 2010 along with a view that school design had worked more in the interests of architects and designers than of users of school buildings. The secretary of state for education, Michael Gove, declared that under his watch there would be no curved or glass walls on any new school buildings. This was part of a bid to reduce costs and standardise design. In this gesture, Gove demonstrated how the design of school buildings does matter and reflects an approach to education which in his case is preferred as traditional. Many of the designs suggested by pupils in this book signal how transparency matters to them in underlining an open and connected school and how curved lines emphasise their preference for nurturing, safe and soft environments.

It is remarkable, in view of the fact that architectural education is very rarely provided within compulsory schooling, that there was such a wealth of material contributed to the collections in 1967 and 2001 about the shape and design of schools. However, some have argued that children are ‘natural builders’ or ‘have a natural talent as planners and designers’ (Hart, 1987; Gallagher, 1998) and that the school curriculum might be better organised to recognise this. Writing in the USA, architecture and design educator Claire Gallagher has noted, ‘The typical means of instruction in our educational culture is either linguistic and/or mathematical. Rarely is any attention paid to visual or spatial thinking or problem-solving’ (1998: 109). Her work with ‘at risk’ elementary school children in designing and planning their own neighbourhoods has illuminated how children have a distinctive knowledge and understanding of spatial environments that policy-makers rarely tap.

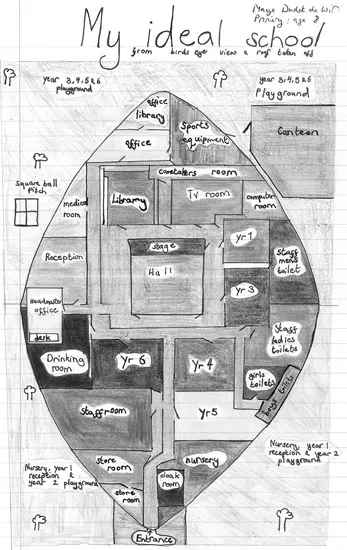

‘The School I’d Like’ competition spontaneously produced dozens of models, hundreds of plans and thousands of implied designs of ideal sites for learning. In addition there was produced a remarkable collection of drawings and paintings through which children have expressed their ideas on curriculum, use of time, role of teachers and form of school. These design ideas address more than the shape of building and the ordering of spaces; they tell of a vision of education that reaches beyond the strict mechanics of building science.

The 1967 competition had also produced entries which were architectural in approach. Indeed, one of the winners at that time was a detai...