![]()

1 Introduction

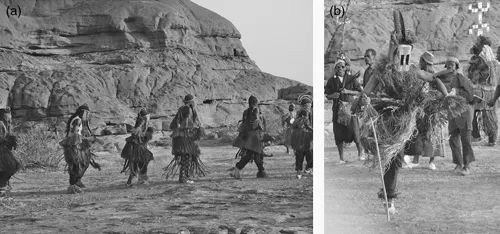

In order to reasonably hope for the survival of our species, with some continuity with the meaningful traditions of our past and retention of the biodiversity of the Earth, we must see heritage preservation and sustainable design integrated together. This is analogous to seeing both the vase and the face in a quintessential Rubin’s Vase image (Figure 1.1). Beyond recognizing each of these bistable forms as unique entities, our societies also need to understand the integral way that these pursuits fit together and define one another. In this book, which is an overview of the concepts that we propose must be merged for students and professionals dealing with the built environment, we seek to illuminate the interface between heritage preservation and sustainable design. Heritage preservation, termed historic preservation in the United States and heritage conservation in the United Kingdom, is the movement to conscientiously care for existing buildings, landscapes, and other artifacts (the tangible) due to their historic significance so that they can endure through time as a record of the past for future generations. Heritage preservation is chosen as the term in this book so as to also include intangible heritage or cultural heritage (as in ideas, customs, traditions, behavioral patterns) in the definition (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 Sustainable design and heritage preservation are not completely discrete entities but must be considered part of the same essential perspective when anticipating a habitable and meaningful planet in the long term.

Image by Amalia Leifeste.

Figure 1.2 (a and b) Intangible heritage in the form of performances and dance is shown here in Dogon country (Pays Dogon) in Mali, in a photograph taken in February 2010.

Photograph by Karmen Unterwegner.

Sustainable design is a facet of sustainability. The definition of sustainability with greatest consensus was generated at the 1987 United Nations (UN) General Assembly and states that sustainable developments “meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs” (Brundtland Commission 1987). Sustainable design looks specifically at the decisions we make with respect to the production of artifacts—from the small scale to the built environment at large—and the impact of those production decisions on environmental quality. As is discussed in Chapter 4, sustainable design and sustainability often relate to an ecological perspective of the planet: how do our methods of production and our products impact the ecosystems of our environment? Thus, what we advocate merging are the objectives of our forward-looking plans about how to build in and inhabit our current and ideal future societies: on one hand, sensitivity toward culturally relevant places, artifacts, and ideas; and on the other, respect for the best possible planetary ecological system. The two disciplines of heritage preservation and sustainable design, highlighted in this work due to how essential each is given our current socio-environmental and political climates, should now be understood as incomplete without an awareness of the other. Natural and cultural heritage preservation were once more conceptually integrated but became much more siloed during the twentieth century. The task of (re)merging our thinking about these arenas of concern requires many reconceptualizations, from the hypertheoretical to the technical. This book seeks to familiarize readers with the argument for commonality between the two fields and to introduce the basic concepts and ideas to be merged. Each chapter of this work could be a book unto itself, and there is much great existing literature through which readers can explore deeper, more technical, yet more siloed presentations of the topics covered here.

Our guiding message is that social-cultural and environmental issues must be addressed together, holistically. We join a small movement of others who share this conviction. Despite the reality that there has been a long history of human behavior that has had an adverse effect on the planet, the authors are not without optimism that we can change our collective behavior and the impact it has on the macro ecosystem contained on Earth. We have the considerable advantage of being able to look back through our long history to dynamic and intriguing material and intangible innovations. Firm dedication to altering our role in the global ecological narrative, when coupled with hindsight and critical thinking, can provide actionable approaches for a more sustainable future—in all of its diversity of meanings. The past can be used as a tool for reaching a better understanding of contemporary problems and can play a role in finding solutions.

This book is a primer for readers familiar with only one, or frankly neither, of the disciplines of sustainable design and heritage preservation. We will explore the extensive and essential compatibility and commonality of the two fields. Frank Matero, a major figure in contemporary preservation practice and education, makes the case that “[s]ince the 1970s sustainability has evolved as a significant mode of thought in nearly every field of intellectual activity” paired with the idea that “[o]ver the past decade heritage has come center stage in the discourse on place, cultural identity, and ownership of the past. This has been due in part to the development of heritage preservation into a field many now consider among the most significant and influential sociocultural movements that affect the built environment” (Teutonico and Matero 2003). Realizing the prominence of these two lines of thinking and seeing cultural heritage preservation as essential to a high-quality environment and means of living, we need to acknowledge how the boundaries of these two fields are porous and perhaps, even, indistinct from one another.

Thus, it behooves someone interested in sustainable preservation to have an understanding of the foundational, essential works of literature traditionally associated with the discipline of sustainable design. Similarly, the foundational texts describing the history of the heritage preservation movement and the philosophies of the field stand to inform a wider audience than future professional preservationists.1 Reading both sustainable design literature and heritage preservation literature, we find affirmation of a deeply ingrained compatibility.

Related Works and Their Different Approaches

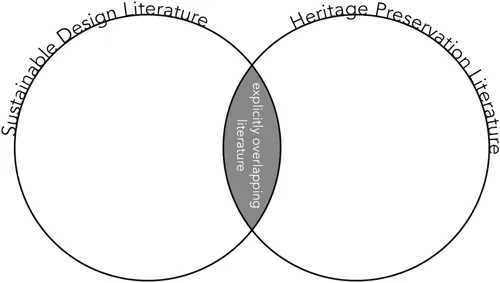

The merge that we are proposing builds on sizable bodies of literature that exist for the disciplines of heritage preservation and sustainable design. When we see these fields of study as separate or distinct, as we have over the past century, the Venn diagram of where this literature explicitly overlaps is a fairly small region (Figure 1.3). This small intersection represents literature that directly addresses both heritage preservation and sustainable design concerns. Defining works include Robert Young’s Stewardship of the Built Environment and Jean Caroon’s Sustainable Preservation: Greening Existing Buildings. These two works represent the first generation of scholarship on sustainability and preservation and make foundational arguments about the compatibility of the two fields. The authors effectively draw examples from existing case studies. Following the tradition of literature in heritage preservation, case studies are a major vehicle for showing the ideas in application and in a specific context. This contrasts with the method and intent of this book, which is an examination of ideas at a more abstract level. Similarly, edited collections such as Routledge’s Explorations in Environmental Studies: Climate Change and Cultural Heritage, A Race against Time or Longstreth’s Sustainability & Historic Preservation: Toward a Holistic View tend to be less primers on the topic of sustainable preservation and more an investigation into a series of specific topics of overlap between the two fields. Fewer overarching narratives of the interconnectedness are synthesized from these works, with greater emphasis on specific, narrow studies of the application of mutually compatible heritage preservation and sustainable design ideas than is the intention behind the work you are now reading.

Figure 1.3 Sustainable design and heritage preservation literature share a small segment of published works and a great deal of commonality beyond the explicit overlap of literature in the two fields.

Image by Amalia Leifeste.

All of these texts address the theory behind sustainable design and heritage preservation with a fairly light touch. The texts are not designed to be an introduction to preservation theory, for example, instead leaving that topic to the many works that exist within the body of preservation literature on the history and theory of heritage preservation. The books from the first generation of sustainable design and heritage preservation literature are generally directed to, and are certainly heavily used by, an audience of heritage preservation students. The assumption is that sustainability is an overlay on a heritage preservation education. Sustainability is brought into the mix once those learning about heritage preservation have a grasp of essential concepts and are primed for the more technical, in-depth, and multifaceted realities of the interplay between sustainable design and heritage preservation. This phenomenon can also be seen recorded in the conference proceedings entitled Managing Change: “[i]f sustainability ultimately means learning to think and act in terms of guaranteeing the prosperity of interdependent natural, social, and economic systems, then heritage with its unique values and experiences must be contextualized and integrated with this view” (Teutonico and Matero, 2003). Strikingly, we do not find much of the inverted situation, where sustainability students engage the discourse of preservation or cultural heritage as an overlay to understand sustainability issues. Thus, through our contribution of Sustainable Heritage, we also hope to fill this void.

In addition to first-generation textbooks or academic works that explicitly address sustainability and heritage preservation, there is a category of books that cover the topic for non-academic audiences. These sources are directed toward an audience of homeowners or building stewards who are interested in the field, as opposed to future or current professional preservationists. Jerry Yudelson’s Greening Existing Buildings, Aaron Lubeck’s Green Restorations: Sustainable Building, and Historic Homes, Stephen A. Mouzon’s Original Green, and Dennis Rodwell’s Conservation and Sustainability in Historic Cities generally follow this pattern of ‘greening,’ ‘contextualizing’ or tying preservation practices and concepts to the sustainability movement. These works also tend to have a preservation-centric audience more than an audience from a background in sustainable design. This bias reveals that heritage preservation, as a field of study, is more concerned with positioning preservation relative to sustainability objectives than is sustainable design relative to heritage preservation. In terms of method, however, these works follow a tradition more familiar to the literature of sustainability where non-subject-area experts are the perceived audience. Because sustainability books like Cradle to Cradle by William MacDonough and Michael Braungart or Rachael Carson’s Silent Spring have a central mission of educating the broad public, generating awareness and inspiring change in the actions of many, the tone of the works are suited to the intention. Mouzon’s work particularly follows this tradition of public education from the intersection of sustainable design and heritage preservation.

Journal articles are building the body of literature at the intersection of sustainability and heritage preservation at a faster rate than published books. Articles that focus on the topics of heritage resources and sustainability have been published extensively in journals rooted in the discipline of heritage preservation, architectural design, sustainability, planning, and archaeology. Within scholarly journals on sustainability and heritage preservation, many articles are naturally narrowly focused. The articles tie together sustainability and heritage preservation with a specific application or highly specialized audience in mind. The Association of Preservation Technology International (APT) has recently made public an annotated bibliography of “Climate Change and Cultural Heritage Conservation” as an updatable, living document. This bibliography is the effort of a team of subject-area experts, and it provides a resource for ongoing literature covering one facet of sustainability concerns (climate change) and heritage preservation. In contrast to a literature review in a book—like the one you are reading—printed and thus fixed at one point in time, the annotated bibliography that is curated by the APT Technical Committee on Sustainable Preservation is intended to continue to develop and grow as new literature is published. The literature presented in APT’s literature review is weighted toward archaeological and cultural landscape articles. This resource is a considerable and dynamic contribution in light of the unfolding literature here at the intersection of sustainability and heritage preservation, though it is not yet comprehensive in its reporting on the available literature.

As a category, publications addressing both fields of heritage preservation and sustainability are fairly recent in vintage. The earliest published book in the area of direct overlap holds a 2007 copyright date. In the last decade, there has been a dramatic bloom. The accelerating rate of publication on this topic is an excellent signal for our collective knowledge and indicates a growing awareness that preservation ethics and sustainable design objectives should again be seen as integrally connected. This is a developing field, with contributions to the topic joining the published literature monthly. The literature at the intersection of sustainability and heritage preservation is growing and deserves considerable scholastic and public attention.

Chapter Organization

Within our volume, we present information that values cultural heritage and environmentally benign design. Beginning with Chapter 2, “Cultural Relationships with Nature, Ecology, Biodiversity, Energy, and Resource Systems,” we summarize the issues societies face due to the often unhealthy relationship between human behavior and ecological systems. Humans, in contrast to other species, have a very unique role on this planet. We dominate the Earth and operate in a way that affects ecosystems in a manner that no other species has ever done in history. Furthermore, we have the fairly unique ability to be cognizant of that fact. Yet we are still subject to the planet’s ecology, energy, and resources systems and processes—despite the artificial built environments that we are capable of producing. The chapter acknowledges that dramatic climate destabilization, more commonly referred to as ‘climate change,’ is clearly attributable to human activities and the fact that, regardless of cause, humans are uniquely positioned to intervene in Earth...