![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

The notion of performance is a key aspect of many domains of human endeavour, and is increasingly recognized as a fundamental component of many related professions. This notion of performance – performing key skills effectively at the right time – is a characteristic of many domains including sport, medicine, acting, musical performance, the military, emergency services, air traffic control, and the performing arts. While there are significant differences between these domains regarding the skills required, the rewards for successful execution, and the consequences for failure, the underpinning psychology appears to be similar.

In looking to better understand the nature of the phenomenon across performance domains it is important to understand the nature of performance itself and the psychological factors that underpin performance. There is much theory and understanding that exists across a broad range of psychological disciplines that has not historically been drawn together to understand the nature of performance, and with that understanding how to maximize individual performance potential.

This chapter will seek to clarify what performance is, and clarify what is meant by the ‘psychology of performance’ and ‘performance psychology’. The chapter will also touch on the notion of flow before presenting an overarching model of factors that determine performance.

Psychology of performance

What is performance?

Performance appears to be a fundamental part of the human experience, with Matthews, Davies, Westerman, and Stammers (2000) in their book on Human Performance suggesting that “Humans beings are born to perform” (p. 1).

Raab, Lobinger, Hoffman, Pizzera, and Laborde (2016) in their book on this topic described being interested in

human performance in everyday life, often in relation to achieving specific goals such as winning a competition in sports, music or arts, improving stabilizing, or re-establishing performance when preparing for such events that are important and meaningful for a group or individual.

(p. 1)

While there is significant interest in the notion of performance it has not historically been well defined. Much has been made of how to perform, but not what performance is. Using the context of sport as an example, performance has specifically been described by Thomas, French, and Humphries (1986) as “a complex product of cognitive knowledge about the current situation and past events, combined with a player’s ability to produce the sport skill(s) required” (p. 259). This definition emphasizes two important components of decision-making: cognitive knowledge; and motor, response execution (Gutierrez Diaz del Campo, Gonzalez Villora, & Garcia Lopez, 2011).

Effective performance (under pressure) has been suggested to involve the consistent execution of complex motor skills in a flawless or near perfect manner (Singer, 2002). Effective performance has also been characterized by an optimal mindset that keeps the performer focused on the task at hand at the expense of other competing stimuli (Gould, Dieffenbach, & Moffett, 2002; Kao, Huang, & Hung, 2013; Krane & Williams, 2006). An associated term of relevance here is that of sport expertise. Sport expertise has been described as the ability to consistently demonstrate superior athletic performance (Janelle & Hillman, 2003; Starkes, 1993).

There is also a distinction between different aspects of performance. In some domains performance is about flawless (or near flawless) execution of complex motor skills to achieve specific targets or goals. In other performance domains the execution of the skills in themselves is the required outcome (e.g. musical or artistic performances).

Psychology of performance

The psychology of performance seeks to understand the cognitions and behaviours initiated by striving for competence or even excellence (Matthews et al., 2000). A range of psychological factors have been highlighted as influencing performance in the short-term and long-term. These include technical and tactical skills, information processing, memory, emotion, and cognition (Raab et al., 2016).

It has also been suggested that the general task of performance psychology relates to the description, explanation, prediction, and optimization of performance-orientated activities. Mitsch and Hackfort (2016) highlighted three specific issues of concern relating to performance psychology: (1) the psychological fundamentals of performance-orientated activities in various action domains; (2) psychological transfer effects of performance-orientated activities in regard to personality development, self-esteem, time management, stress control, communication skills, etc.; (3) optimization of the capability to achieve demanding mental tasks. Put simply, the psychology of performance is about understanding the psychological factors that both influence and determine performance.

Performance psychology

During the last 15 years, and due in part to an increasing appetite from performance domains outside of sport, we have witnessed the emergence of the professional field of performance psychology. Despite being a developing field, performance psychology is beginning to have an increased appreciation within the scientific literature (Barker, Neil, & Fletcher, 2016). A range of definitions of performance psychology have been suggested including this definition suggested by Hays (2012, p. 25), “performance psychology refers to the mental components of superior performance, in situations and performance domains where excellence is a central element”. Understanding the psychology of performance though goes beyond just the mental components and should also consider the importance of the interaction between the individual and the environment in which they perform. Performance psychology focuses on the psychology of human performance in domains such as sport, the performing arts, surgery, firefighting, law enforcement, military operations, business, and music. Presently, evidence-based practice in performance psychology focuses on performance excellence and/or restoration and well-being in individual performers and groups (Cremandes et al., 2014). One associated term is that of flow. Swann, Keegan, Piggott, and Crust (2012) highlighted the importance of flow states which have been consistently linked to the notion of peak performance, for elite performers under pressure. A perspective supported by Broomhead et al. (2012) who highlighted the impact that a positive mindset can have upon musical performance.

Flow

Csikszentmihalyi (1990) used the collective term ‘flow’ to group the characteristics of peak psychological performance states. Flow was specifically defined by Csikszentmihalyi (1975) as “an optimal and positive psychological state attained through deep concentration on the task in hand and involving total absorption”. Flow experiences tend to be harmonious for the individual and involve a sense of everything coming together, or clicking into place, even in challenging situations. Based on these feelings the performer is often left feeling that something special has just occurred and those experiences can be highly valued and positive (Csikszentmihalyi, 2002; Jackson & Csikszentmihalyi, 1999). Csikszentmihalyi (2002) outlined nine dimensions that are proposed to combine and interact to make up these flow experiences. These dimensions have subsequently been divided into flow conditions and flow characteristics (Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Flow conditions are prerequisites for flow to occur, and include: challenge-skills balance (e.g. situations that are challenging to the individual, but in which they are still able to meet the challenge by extending beyond their normal capabilities in order to accomplish the task); clear goals inherent in the activity for the individual to strive towards; and unambiguous feedback to either inform the athlete that they are progressing towards these goals, or tells them how to adjust in order to do so. Flow characteristics describe what the individual experiences during flow, including: concentration on the task at hand (e.g. complete focus with no extraneous or distracting thoughts); action-awareness merging (e.g. total absorption, or feeling at one with the activity); loss of self-consciousness (e.g. decreased awareness of self and social evaluation), while a sense of control over the performance or outcome of the activity can also be experienced, as can a transformation of time (e.g. the perception of time either speeding up or slowing down). The combination of these dimensions led to flow being characterized as an autotelic experience, a term Csikszentmihalyi (1975) used to describe these experiences as being enjoyable and intrinsically rewarding. Flow states have been associated with increased well-being (Haworth, 1993), enhanced self-concept (Jackson, Thomas, Marsh, & Smethurst, 2001), positive subjective experience (Csikszentmihalyi, 2002), and (crucially) performance (Jackson & Roberts, 1992). Gould, Eklund, and Jackson (1992, p. 362) in their report on Olympic Wrestlers also concluded that these optimal performance states

have a characteristic that is referred to variously as concentration, the ability to focus, a special state of involvement, the zone, flow state, ideal performance state, awareness and/or absorption in the task in hand. In this state of mind, the athlete is totally absorbed in task-relevant concerns.

Flow is particularly relevant for elite performers who apply their skills at the highest levels, under the most intense pressure, and with the greatest rewards at stake. At these levels even minor improvements could have significant impacts on performance outcomes (Swann et al., 2012). Furthermore, Catley and Duda (1997) reported that skill level is significantly correlated with the experience of flow, while Engeser and Rheinberg (2008) also suggest “it is likely that individuals with higher ability have higher flow values” (p. 161). As a result, coaches, performers, and psychologists have been committed over the past 25 years to developing systematic and consistent strategies to allow the performers or teams to achieve this peak performance state.

Model of performance psychology

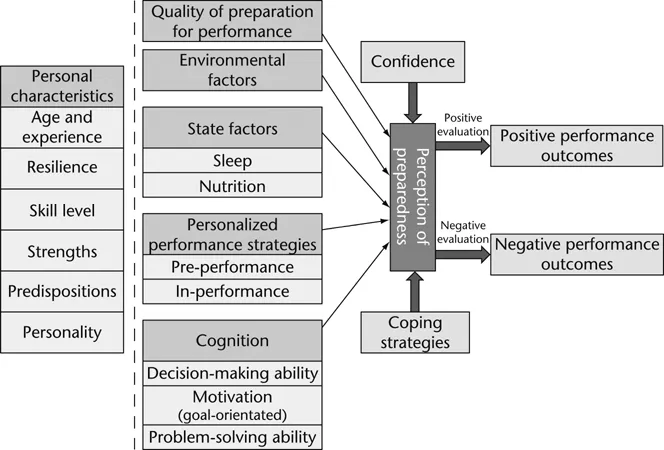

While many authors discuss the psychology of performance, and performance more broadly, this is often from a very specific perspective. This means that the ‘bigger picture’ perspective is often lost. This book seeks to present a coherent overview of a range of related factors that all both influence and determine human performance. Presented in Figure 1.1 are a range of empirically supported factors that to varying degrees determine the degree of success that is achieved. Specific components of the model include: the performer (and their individual characteristics), the quality of preparation for performance, environmental factors, state factors, cognition, confidence, coping strategies, and the architecture of the human body and neural processes.

The remaining chapters of this book will systematically explore each of these factors in detail. Chapter 2 introduces key aspects of the human ‘machine’, focusing on human performance. The chapter specifically explores the nervous system, nutrition for cognition and performance, and also the importance of sleep and recovery. Chapter 3 considers cognition and cognitive processes. It specifically explores cognition, creativity, problem solving, and perception. The fourth chapter focuses on the psychological construct of pressure. It explores sources of pressure, response of the individual, and relevant coping strategies. Chapter 5 considers the decision-making process and key influencing factors. Chapter 6 focuses on the role of emotion in determining performance. The seventh chapter explores the importance of resilience to performance under pressure. The chapter also explores associated constructs including mental toughness, hardiness, and grit. The eighth chapter focuses on the impact ageing can have on performance ability, considering the mediating role that accumulated experience can have on performance levels. Chapter 9 focuses on the importance of confidence in influencing performance, and crucially how to increase confidence beliefs. The tenth chapter explores the use of psychophysiology to understand performance, but also to look at how psychophysiological indicators can be used to enhance performance. The eleventh chapter explores how to develop effective motor skills, which are seen as one of the key foundations for effective performance. Chapter 12 considers some of the key psychological skills that can be both developed and utilized to enhance performance under pressure. Chapter 13 considers how performers can most effectively practice and prepare for the performance environment. The final chapter considers what the future directions for research might be relating to performance. Also, the key questions that need to be addressed in terms of applied practice and performance.

Study questions

How would you describe the concept of performance psychology?

To what extent do you feel experiences of flow are important to achieving successful performance outcomes?

Further reading

Matthews G., Davies, D. R., Westerman, S. J., & Stammers, R. B. (2000). Human performance: Cognition, stress and individual differences. Hove: Psychology Press.

An important ‘broader’ psychology text that seeks to provide a coherent overview of human performance and the underpinning psychological factors.

Raab, M., Lobinger, B., Hoffmann, S., Pizzera, A., & Laborde, S. (2016). Performance psychology: Perception, action, cognition, and emotion. London: Academic Press.

A very interesting contemporary text that explores performance psychology specifically from the perspective of perception, action, cognition, and emotion.

![]()

2

HUMAN PERFORMANCE

Introduction

Many authors have considered the effect that a wide range of psychological constructs and functions can have upon human performance. However, what has been considered less frequently in the performance literature are those factors that underpin the operation of the brain and the central nervous system.

There are limitations to human performance that are imposed by the architecture of the human body. At a fundamental level this includes the design of the system, its organization, and the structure of basic components such as neurons. There are also limitations based upon the fuelling and regeneration/recovery of the human performance system. In terms of nutrition there is also a reason why the body requires a range of specific vitamins and minerals to perform effectively. There is also variability in performance based on when meals are taken, and what those meals are compose...