![]()

Part I

A Broader Perspective on Agenda Setting

Theoretical and Methodological Foundations

![]()

1

A Theoretical Explication of the Network Agenda Setting Model

Current Status and Future Directions

Lei Guo

BOSTON UNIVERSITY

As early as 1922, Walter Lippmann’s Public Opinion suggested that the news constructs a pseudo-environment for the public, bridging “the world outside and pictures in our heads.” In the following decades, communication scholars developed a number of media effects theories and models, and empirically examined the impact of news media on individuals’ cognitive understanding of the world, as well as on their motivations, attitudes and behaviors. As one communication textbook notes, “The entire study of mass communication is based on the premise that the media have significant effects” on the public (McQuail, 1994, p. 327).

In the pre-Internet era, the premise of significant media effects held true almost undoubtedly in many different socio-cultural contexts. Traditional news media such as newspapers, television and radio disseminated information to large segments of the population, to a great extent deciding how people think, feel and behave. The emergence of the Internet, however, seems to have revolutionized the entire media landscape. The wide availability of new media production and distribution platforms has transformed the previous audience to citizen journalists, prosumers and producers (e.g., Napoli, 2011; Rosen, 2008, 2010). As a response to these changes, media scholars have questioned whether it is still relevant to distinguish between mass and interpersonal communication and, more importantly, whether the media still have significant effects. Here, the media refer to news organizations based on professional journalism practices.

The Network Agenda Setting (NAS) Model, the third level of agenda setting introduced in this book, offers a bold new theoretical and methodological perspective to answer these questions. The NAS Model asserts that the news not only tells us what to think and how to think, but also determines how we associate different messages to conceptualize social reality. As the existing NAS studies demonstrate, the media still set the public agenda, and do so in more complicated ways through constructing information networks than the first and second level of agenda-setting theory have conceptualized (Guo, 2013; Guo & McCombs, 2011a, 2011b; Vargo, Guo, McCombs & Shaw, 2014; Vu, Guo & McCombs, 2014). By visualizing and comparing the information networks in the news and in the public discourse, the Network Agenda Setting Model vividly reveals the impact of the media in shaping the “pictures in our heads.” Although the findings based on a limited number of studies are not yet conclusive, the empirical evidence does showcase that the news media are still powerful, and may even be more powerful than we previously have assumed, in affecting public opinion in this digital age.

In addition to empirically exploring the role of the news media in this transforming media environment, the NAS Model is also important in providing a new theoretical and methodological perspective to examine how people process mediated information. Therefore, such a networked perspective is not only useful in measuring media effects, but it can also be applied to the evaluation of intermedia agenda setting (Guo et al., 2015), public relations campaign effects (Guo & Vargo, 2015; Kiousis et al., 2015), and potentially to other communication research areas as well.

This chapter details the theoretical framework of the NAS Model, clarifying how this model differs from other media effects theories and models, and therefore, how it can further contribute to our understanding of the interplay between mediated information outside and our internal world.

From Hierarchical to Network Agenda Setting

Core to agenda-setting theory is the transfer of salience, or the perceived prominence, of elements from the media to the public agenda (McCombs, 2004, 2014; McCombs & Shaw, 1972). Here, elements refer to objects such as public issues, political candidates and consumer brands, or attributes that describe a given object (McCombs & Ghanem, 2001). The first level of agenda setting asserts that the public considers objects that are prioritized in the news as the most important. The second level of the theory focuses on attributes, stating that the properties or characteristics the news media use to portray a certain object will influence how the audience perceives that object. In other words, the news not only determines what we think about, but also affects how we think about a given topic. Since the 1972 Chapel Hill study, more than 400 studies have empirically demonstrated the agenda-setting power of news media in a wide variety of socio-cultural contexts (Zhou, Kim & Kim, 2015).

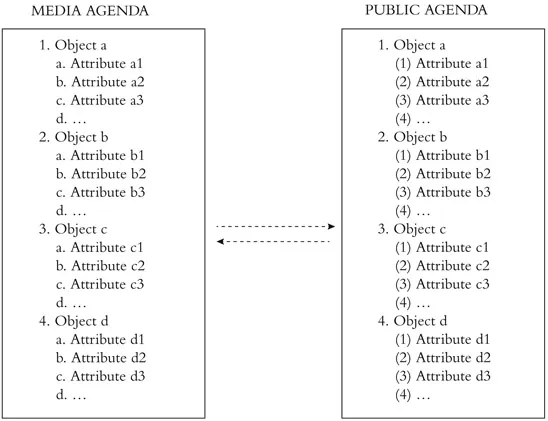

For both the first and second levels of agenda setting, the focus of investigations is hierarchical media effects. News attention, or the amount of news coverage, measures the rank order of object or attribute salience on the media agenda, which in turn affects the relative importance of each element in the public’s mind. As Figure 1.1 demonstrates, traditional agenda-setting research considers human’s mental representation from the perspective of a hierarchical linear model. The underlying assumption is that when we consider what is happening in society or think of a particular subject, we will spontaneously generate a ranked list of issues or attributes in our mind. Put another way, research on the first and second levels of agenda setting focuses on the salience of the discrete, isolated elements that define the hierarchical agenda.

Figure 1.1 Hierarchical agenda setting

Unlike previous agenda-setting research, the NAS Model turns attention to the networked media effects. The model focuses on the networked relationships among issues, attributes and other elements rather than the salience transfer of individual elements per se. In the traditional view, the salience of individual objects and attributes on the media agenda influences the salience of those elements on the public agenda. In contrast, the core hypothesis of the NAS Model asserts a much broader and stronger hypothesis:

The salience of media networks of objects and attributes influences the salience of the networks of these elements among the public.

In other words, the ways in which news media associate different objects, attributes and other constructs will impact the public’s cognitive network.

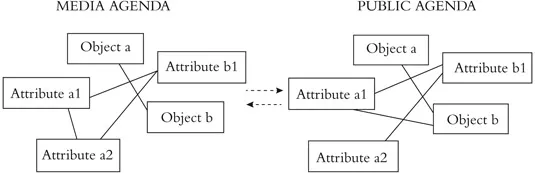

For instance, if U.S. news reports recurrently emphasize the link between rising unemployment in the United States and its trade with China, the audience will also consider the two issues as related. In this process, the news media construct a semantic link between the two distinct elements and make the link—rather than the individual elements—salient in the public’s mind. Note that the semantic relation and distance between issues and/or attributes does not necessarily correspond to reality. Neither is it fixed in the public discourse. The news media, among other external stimuli, may create new links and even alter the long presumed semantic relation and distance between different messages. Ultimately, as illustrated in Figure 1.2, the entire set of links—the information networks—can be transferred from the media to the public agenda.

Figure 1.2 Network agenda setting

The network of nodes that represents the news coverage is termed the media network agenda. The network of nodes that represents public opinion is called the public network agenda. Methodologically, the network agenda setting analysis compares the two network agendas and measures the degree of correlation. (See Chapter 2 for methods to conduct NAS studies.)

To date, a number of studies have provided empirical support to the NAS Model. Based on data from the 2002 Texas gubernatorial election, Guo and McCombs (2011a) compared the ways in which a major Texas-based newspaper associated different personal attributes (e.g., leadership, credibility and intelligence) to portray the two political candidates with the ways Texas residents in the newspaper’s home city described the candidates. Results showed significant correlations between the media and public network agenda. In other words, the public’s mind did mirror the attribute networks constructed in the news. The authors replicated the study using data collected in the 2010 Texas governor election and found similar significant results (Guo & McCombs, 2011b). It appeared that the mainstream newspaper still determined how voters pictured the politicians at the time when new media outlets such as blogs, Facebook and Twitter started to emerge and grow.

Given that the first two exploratory studies examined the network agenda-setting effects on attributes in state-level political elections, Vu et al. (2014) sought to expand the scope of the NAS Model to a non-election time and to the national level. By testing five years (2007–2011) of aggregated data from national news media and polls, their study demonstrated that the salience of the network relationships among issues such as economy, politics, health, education and environment can be transferred from the news media to the national audience in their daily lives as well. To further investigate the NAS Model in the new media environment, Vargo, Guo, McCombs and Shaw (2014) directly examined the impact of the news media on the public discussion in Twittersphere during the 2012 U.S. presidential election. The results provided strong evidence for the NAS Model in this social media platform. Specifically, the study showed that while Obama supporters were more likely to follow the issue network agenda constructed by the vertical, mainstream media, the horizontal, partisan media were found to be more effective in influencing the cognitive networks of Romney supporters.

More recently, researchers have applied the NAS Model in non-Western contexts. Wu and Guo (2015) examined the news media’s network agenda-setting effects during Taiwan’s 2012 presidential election. The study analyzed both issue networks and networks of attributes that described the two political candidates. The results showed that the NAS effects were stronger at the attribute than the issue level. In a non-election setting, Cheng and Chan (2015) investigated how the mainstream newspapers in Hong Kong associated different attributes in their coverage of a social movement and then compared the news coverage with the public network agenda. Significant network agenda-setting effects were found.

While some also found the flow of influence from the public to the media network agenda in different scenarios, the majority of the existing studies suggest that professional news organizations were more likely to set the public agenda rather than vice versa. The news media’s power in setting the public agenda remains strong. Considering the unique theoretical focus of the NAS Model as well as the solid empirical evidence found in a number of studies, Maxwell McCombs, one of the founders of agenda setting, coined the term, the third level of agenda setting, to describe the NAS Model in his recent book, Setting the Agenda (McCombs, 2014, p. 55).

However, questions arise as to how the NAS Model is significantly different from other media effects models and what new level has been added to our understanding of media effects. Indeed, the examination of semantic networks is not new in communication research. Many other media effects theories such as framing and priming, as well as the first and second level of agenda setting, all seek to explain the ways in which the news messages affect our cognitive networks. In order to better explicate the NAS Model, the next section describes its underlying information-processing mechanism and clarifies how the NAS Model is conceptually different from other media effects theories and concepts.

Information-Processing Mechanism

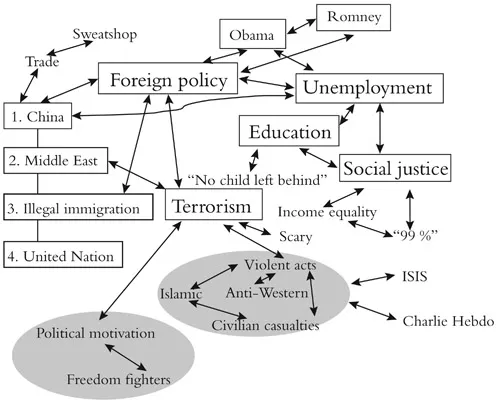

According to an associative network model of memory, our cognitive understanding of external social reality is presented in our mind as a network-like picture where numerous nodes are connected to one another (Kaplan, 1973). Figure 1.3 illustrates a portion of a person’s cognitive network. As the figure shows, nodes in a network can refer to any unit of information including single words and phrases; objects and their attributes; goals, values and motivation; affective or emotional states; higher level constructs such as schemas; as well as sensual information such as vision, hearing and smelling (Lindsay & Norman, 1977; Price & Tewksbury, 1997; Rumelhart & Norman, 1978). The cognitive network includes linear and hierarchical thinking structures, the focus of traditional agenda-setting research, as well as a mixture of various sub-networks.

Figure 1.3 An example of a cognitive network...