The puzzle: why warm peace in Europe vs. shifts between (hot/cold) war and (cold) peace inthe Middle East?

The fall of the Berlin Wall twenty-five years ago solidified the spread of peace on most of the European continent. This peace emerged first in West Europe in the aftermath of WWII, evolving into what I’ll call here “warm peace,” which has spread after the end of the Cold War into the central-eastern part of the continent. Post-WWII Middle East, in contrast, suffered from quite a few wars; only in the late 1970s, a cold peace emerged between two major antagonists – Egypt and Israel, while cold war, interrupted by episodes of violence, including low-intensity or asymmetric warfare, has continued to dominate large parts of the region.

How could International Relations (IR) theory explain these variations in the level of war/peace between the two regions? Europe and the Middle East look very different, but there are also certain similarities between them. Both regions were characterized by major rivalries. While this is obviously still the case in the Middle East, the Franco-German antagonism continued at least for a decade after the end of WWII. Moreover, in the two regions, both realist and liberal mechanisms were used to advance peace. So why is there such a variation in the level of war and peace between the two regions? I argue that while the combination of realist and liberal factors resulted in warm peace in Europe, peace-producing realist factors came much later to the Middle East and in a weaker form than in Europe. Moreover, while liberal mechanisms were attempted in the Middle East, the pre-requisites for their peace-promoting effects – especially those related to stateness and congruence between geopolitical boundaries and national identities and loyalties – are missing or at any rate are in a much weaker level than in Europe.

What are the main causes of the warm European peace, and to what extent do they apply in other regions? There is a realist–liberal debate on the sources of the European peace and thus potentially also on their application into other regions. The realist–liberal distinction, however, is insufficient. I distinguish here among four approaches to peace and security based on a novel distinction not only between realism and liberalism, but also on an internal division inside each camp between offensive and defensive approaches. Indeed, besides the familiar distinction bet ween offensive and defensive realism, there is also an overlooked parallel distinction between offensive and defensive liberalism. Thus, we get four distinctive approaches: defensive realism, offensive realism and also defensive liberalism and offensive liberalism.

This article focuses on this novel four-fold distinction and its application to regional security, particularly in two key regions: Europe and the Middle East. I argue that the combined effect of the realist mechanisms produced “cold peace” in Europe, while the liberal strategies warmed the peace considerably, eventually producing a “high-level warm peace.” More specifically, it was the overlooked offensive liberal mechanism which made an especially major contribution to the emergence of warm peace on the continent through the successful imposition of democratization on the key state for European security – Germany (initially, of course, West Germany). Defensive liberal strategies then played a very useful supportive role in warming the regional peace. Yet, the peace-producing effects of the liberal mechanisms heavily depend on the presence of what I call a regional state-to-nation balance: to what extent the regional states are capable states whose boundaries are congruent with the national aspirations, identities and loyalties of the key groups in the region (Miller 2007).

In the Middle East, in contrast, some of the conditions for the application of the realist approaches emerged only after the 1973 war and only in the Israeli–Egyptian context, and then somewhat more broadly after the end of the Cold War and the 1991 Gulf War. But the conditions for the liberal strategies are still missing even though a defensive liberal strategy has been tried in the l990s and an offensive liberal strategy has been applied since 2003. Thus, at best, only a cold peace could emerge and even that only partially due to the relative weakness also of the realist mechanisms (both offensive and defensive) in the Middle East in comparison to the West European case during the Cold War.

In what follows, I initially differentiate among types of regional security outcomes: hot/cold war and cold/warm peace. The task then is to examine what the different approaches suggest on the avenue to accomplishing peace in general and durable “warm” peace in particular. Following a conceptual discussion of the offensive and defensive realist approaches, I analyze the offensive and defensive libe ral conceptions of peace and security. The next sections apply the realist and liberal approaches to Europe and to the Middle East. On the whole, I show that the successful application of all four approaches brought regional peace to Europe – the realist strategies producing initially cold peace and then the liberal ones elevating it to warm peace. In contrast, only the realist strategies were effective in the Middle East, but much later than in Europe, and even then only partially. Thus these strategies produced at best a fragile and partial cold peace with still strong regional elements of cold war. In the last decade, this regional cold war/peace has been interrupted by the eruption of large-scale hot civil wars and transborder violence, especially as a result of the US invasion of Iraq and the Arab Spring, as well as the continuous Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

In order to bring about peace to the Middle East, first of all the realist mechanisms have to be implemented more forcefully under an intensive hegemonic leadership. This leadership should be able to provide an effective security umbrella to the regional states taking part in the peace process against common revisionist threats. This leadership has then to focus on mediating key regional conflicts, but together with other international players and the regional actors, it should also focus on helping state-building and nation-building processes in the region. Only then the liberal mechanisms can be effective and warm and stabilize the regional peace as was the case in post-WWII Western Europe.

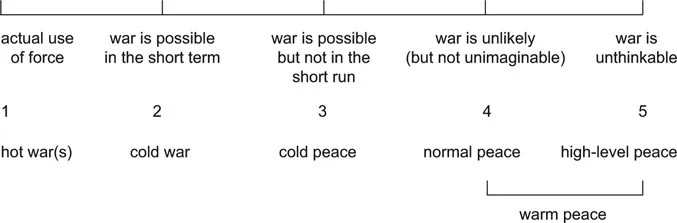

Figure 1.1 distinguishes between five types of regional security or war and peace outcomes according to the probability of the use of force:

1. Hot war is a situation of actual use of force aimed to destroy the military capabilities of the adversaries. The Middle East is among the most violent-prone regions in the post-WWII international system. Thus, major examples for hot war come from this region including the Arab–Israeli wars (l948–1949, l956, l967, 1969–1970 l973, l982 and most recently the Second Lebanon War of 2006 and the Cast Lead Operation of 2008–2009), the Iran–Iraq War (l980–1988), and the Gulf War of 1990–1991.

Figure 1.1 A war–peace continuum

2. Cold war is a situation of negative peace1 – a mere absence of hot war in which hostilities may break out any time. It is characterized by recurrent military crises and a considerable likelihood of escalation to war, either premeditated or inadvertent.2 The parties may succeed in managing the crises, avoiding escalation to wars while protecting their vital interests,3 but they do not attempt seriously to resolve the fundamental issues in dispute between them. As to means employed by the parties, a cold war is characterized by the use of military forces for show-of-force purposes such as influencing the intentions of the regional rivals through deterrence and compellence.4 Diplomacy plays an important role in the parties’ relations, but it is largely a diplomacy of violence – the use of military means for diplomatic ends – for signaling, crisis management, and to clarify interests, commitments, and “red lines.” An important component of cold war situations is the diplomacy of regional hot war termination, manifested in the establishment of cease-fires or armistices.5 The presence of enduring rivalries in the region is a key indicator of a cold war there.6

Examples include the periods between the hot wars between Israel and its Arab neighbors, namely, l949–1956, l957–1967, l968–1973, etc.

3. Cold peace is a situation characterized by formal agreements among the parties and the maintenance of diplomatic relations among them. The underlying issues of the regional conflict are in the process of being moderated and reduced, but are still far from being resolved. The danger of the use of force is thus unlikely in the near future, but it still looms in the background and is possible in the longer run if changes in the international or regional environment occur. In one or more of the regional states, there are still significant groups hostile to the other states, and thus the possible coming to power of belligerent opposition groups in these states may also lead to renewed hostilities or a return to cold war. The parties still feel threatened by increases in each other’s power and are concerned with relative gains.7

Military force is not used in the relations between the parties, not even for signaling and show-of-force purposes. Rather, the focus is on diplomatic means for the purposes of conflict reduction or mitigation,8 and the parties seriously attempt to moderate the level of the conflict through negotiations and crisis-prevention regimes.9 These efforts, however, stop short of a full-blown reconciliation among the parties. Foreign relations among the regional parties are conducted almost exclusively through intergovernmental diplomacy, and there are limitations on transnational activity which involves nongovernmental players. The parties still develop contingency plans that take into account the possibility of war among them. Such plans include force structure, defense spending, training, type of weapons, fortifications, military doctrine, and war planning.

Examples include the Israeli–Egyptian peace since l979 and the Israeli–Jordanian peace since l994. Inter-governmental negotiations succeeded to reach formal peace agreements between them. These peace accords have reduced the level of conflict between Israel and these two Arab neighbors. Especially critical is the peace between Israel and Egypt as the relations between them are the key strategic relations in the Arab–Israeli context. Since they have moved to the cold peace level, the likelihood of the eruption of a major inter-state Arab–Israeli hot war has drastically declined.

Yet, so long as the Palestinian problem is not resolved, the conflict between Israel and Egypt and Jordan is also not fully resolved. Thus, the relations did not move much beyond the governmental diplomatic channels, and there are only minimal inter-societal exchanges. In other words, the peace is between governments, not the respective societies.

Warm peace refers to a low likelihood of war in the region and to much more cooperative relations among the regional states relative to cold peace. There are two types of warm peace – normal and high-level peace:

4. Normal peace is a situation in which the likelihood of war is considerably lower than in cold peace because most, if not all, of the substantive issues in the conflict between states in the region have been resolved. Regional states recognize each other’s sovereignty and reach an agreement on issues such as boundaries, resources allocation, and refugee settlement. This peace is more resilient than cold peace. Still, war is not out of the question in the longer run, if governing elite or the nature of domestic regime in one or more of the key regional states change. Relations among the regional states begin to develop beyond the intergovernmental level, but the major channels of communication and diplomacy are still at the inter-state level.

South America in recent decades, especially its Southern Cone, might be a good example of this type of peace.10 As K. J. Holsti suggests, in the 20th century, this region has become a no-war zone where mutually peaceful relations and non-violent modes of conflict resolution are the norm.11 While South American states have only rarely fought one another, the region has shown a marked inclination towards conflict settlement as compared to other regions, for example, by frequently using arbitrage procedures and subscribing to many multilateral treaties.

5. High-level peace reflects a still higher degree of stability of peace. It is a situation in which the parties share expectations that no resort to armed violence is possible in the foreseeable future under any circumstances, including government change in any of the states or a change in the international setting. There is no planning by the regional states for the use of force against each other, and no preparation for war fighting among them. There are institutionalized nonvio-lent procedures to resolve conflicts, and these procedures are widely accepted by the elites in government or outside of it in ...