eBook - ePub

Alternate Light Source Imaging

Forensic Photography Techniques

- 82 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Alternate Light Source Imaging provides a brief guide to digital imaging using reflected infrared and ultraviolet radiation for crime scene photographers. Clear and concise instruction illustrates how to accomplish good photographs in a variety of forensic situations. It demonstrates how tunable wavelength light sources and digital imaging techniques can be used to successfully locate and document physical evidence at the crime scene, in the morgue, or in the laboratory. The scientific principles that make this type of photography possible are described, followed by the basic steps that can be utilized to capture high quality evidentiary photographs.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Electromagnetic Radiation

Photography allows the forensic scientist and crime scene investigator the means by which to document the scene and articles of evidence that may be presented before a judge and jury. Frequently, physical evidence must be discovered using tunable wavelength light sources. Trace evidence, fingerprints, body fluids, and other forms of evidence may be discovered using light sources that emit radiation ranging from the ultraviolet (UV) to the infrared (IR) spectrum. The photographer must be able to successfully capture an image of this evidence using the same light source. In order to learn how to capture images using alternate light sources, the photographer must understand the medium, light, and how it relates to the camera.

The interaction between light (or electromagnetic radiation) and matter has been scientifically studied and used to both characterize and identify substances. The advancement of this science is best seen in the field of analytical spectroscopy where very small quantities of an analyte can be exposed to electromagnetic radiation. The manner in which an analyte responds to radiation may be characteristic of a known substance. The examination of evidence with the use of an alternate light source is similar. The physical properties of evidence or the surface on which evidence may reside can facilitate the reflectance, transmission, and absorption of light. Furthermore, the absorption of light by a substance may result in fluorescence or phosphorescence, instances where the substance reemits light. When using light to examine physical evidence, it is of course important to understand the nature of light and how it may interact with a substance. With this knowledge, the characteristic properties of a forensic sample can be recognized and documented. In this chapter, the electromagnetic spectrum and properties of light will be discussed.

1.1 Light and the Electromagnetic Spectrum

Electromagnetic radiation is a radiant energy that exhibits wave-like motion as it travels through space. Everyday examples of electromagnetic radiation include the light from the sun; the energy to cook food in a microwave; X-rays used by doctors to visualize the internal structures of the body; radio waves used to transmit a signal to the television or radio; and the radiant heat from a fireplace.

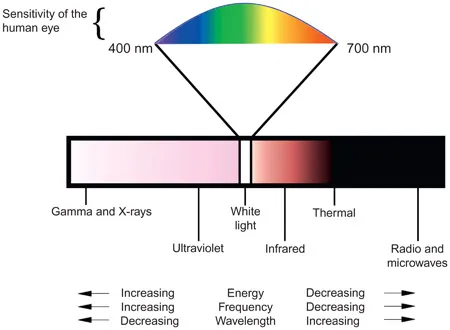

Figure 1.1 The electromagnetic spectrum is the distribution of all electromagnetic waves arranged according to frequency and wavelength.

Electromagnetic radiation can be divided into several categories that include gamma and X-rays, UV radiation, visible light, IR radiation, thermal radiation, radio waves, and microwaves. When electromagnetic radiation is categorized according to wavelength, it is referred to as the electromagnetic spectrum (Figure 1.1).

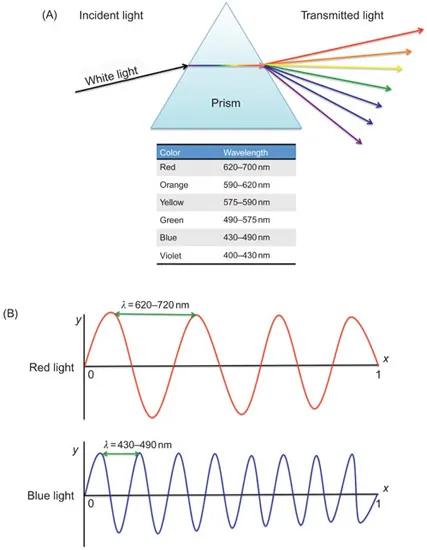

Visible light or white light comprises the individual colors of the rainbow. This is evident when light passes through a prism and is separated into its component colors. The different colors correspond to different wavelengths and frequencies of visible electromagnetic radiation. Red light has a longer wavelength, lower frequency, and lesser energy than blue light. The order of the visible light spectrum based on increasing wavelength and decreasing energy is violet, indigo, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red (Figure 1.2).

Visible light comprises only a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, but it is the only part that humans can perceive without the aid of a detector. Our eyes are most sensitive to green light. Digital cameras have sensor elements that are designed to mimic how we perceive colors. For example, in a camera that possesses a Bayer filter over its sensor, there are typically twice as many green filters as there are blue and red. The imaging sensors used in digital cameras are also sensitive to UV and IR radiation. However, in order to take advantage of the full sensitivity to UV and IR radiation, the camera needs to be stripped of its internal filters.

Figure 1.2 (A) As white light passes through a prism, it is refracted or bent and consequently separates into its component colors. Red light having the longest wavelength deviates the least from the original path of light, whereas blue light refracts the most. (B) Red light will have a longer wavelength than blue light. As implied in Eq. (1.1), there is an inverse relationship between frequency and wavelength. In this graphical example, it can be seen that the shorter the distance between waves, the greater is the frequency increase with a given distance and period of time.

The term infrared refers to a broad range of wavelengths, starting from just beyond red to the start of those frequencies used for communication. The wavelength range is from about 700 nm up to 1 mm. The region adjacent to the visible spectrum is called the “near-IR,” and the longer wavelength region is called “far-IR.”

The region just below the visible spectrum in is called the ultraviolet. The wavelength range is from about 10 to 400 nm. Ultraviolet means the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that is shorter in wavelength than the color violet. The region adjacent to the visible spectrum is called the “near-UV.” Most solid substances absorb UV very strongly.

1.2 Properties of Light

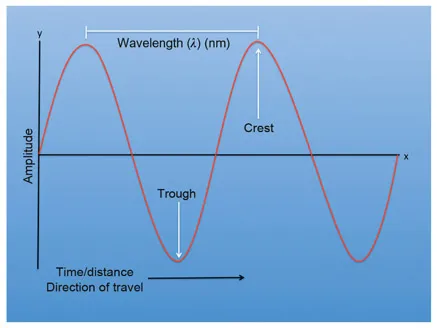

Figure 1.3 The properties of waves include wavelength, frequency, and speed. The wavelength is typically represented by the Greek letter lambda (λ) and is the distance between wave crests measured in nanometers (nm). The wavelength represents one complete cycle of a wave. The frequency of a wave is the number of crests that occur within a given period of time, and the speed of the wave is the distance that it travels per unit time.

As light propagates through space, it exhibits wave-like motion. Waves have three primary characteristics: wavelength, frequency, and speed (Figure 1.3). In a vacuum, all electromagnetic radiation travels at the same speed, the “speed of light,” which is approximately 2.9979 × 108 m/s. A wavelength can be defined as the distance between two consecutive peaks or valleys in a wave. Frequency is the number of waves that pass a single point in a given period of time. Speed, frequency, and wavelength are related by the equation:

where

- c = the speed of light (m/s)

- ν = frequency (1/s)

- λ = wavelength (m)

There is an inverse relationship between frequency and wavelength. Short wavelength radiation has a high frequency. The wave with the longest wavelength will have the lowest frequency. Throughout this chapter, we will be describing several different types of electromagnetic radiation and the tools used to detect and photograph the radiation. The convention that will be used to characterize the radiation will be wavelength, using distance units of nanometers (nm). A nanometer is a unit of distance measurement that is equivalent to 1 billionth of a meter. In forensic photography there are three areas of the electromagnetic spectrum that can be imaged with silicon sensor based digital SLR cameras. The near-ultraviolet region of the electromagnetic spectrum ranges between 300 and 400 nm, the visible region between 400 and 700 nm, and the near-IR region from 700 to 1100 nm.

1.3 Light and Matter

When electromagnetic radiation is incident on matter, the radiation can be reflected, transmitted, absorbed, or a combination of the three. Understanding how radiation interacts with matter and how wavelength selection can be used to enhance evidentiary material is the basis for forensic photography.

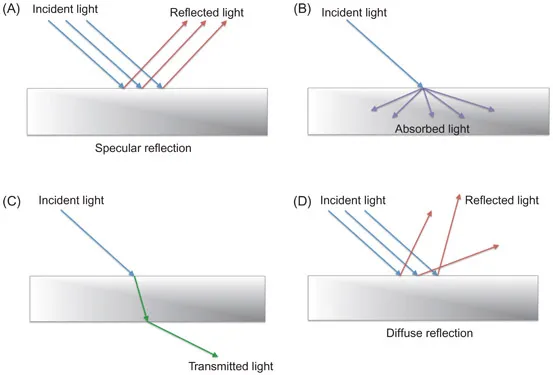

Reflection occurs when light is incident onto an object and it bounces or is reflected. The light reflected could be characterized as specular reflection or a diffuse reflection. Specular reflection occurs when light is reflected from a flat or smooth surface. In a specular reflection, the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection, and the reflected rays are parallel. Diffuse reflection occurs with textured surfaces. The incident illumination is diffused or scattered in many directions from the surface of the object (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Radiation can be (A) reflected, (B) absorbed, or (C) transmitted by an object. In specular reflection, the reflected rays are typically parallel to each other. Diffuse reflection (D) differs from specular reflection (A) in that the reflected rays are not parallel due to the nonuniform surface.

When white light reaches the surface of an object, the object can absorb some or all of the incident illumination. If the object absorbs all of the radiation, it will appear black. If the object reflects all the illumination, it appears white. When an object absorbs light, the light energy is converted into heat energy. This is why it is not recommended to wear dark colored clothing on a hot summer day. Dark clothes will absorb the light and transform the electromagnetic radiation into heat energy, whereas light colored clothes will reflect much of the light.

On a molecular level, when an object absorbs the incident illumination, a portion of the object’s molecular structure is promoted to an electronically excited state. When it is in an excited state, several things can happen: the energy may be transformed into heat energy, or luminescence may occur. Luminescence is the release of radiation by a molecule, or an atom, after it has absorbed en...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Chapter 1 Electromagnetic Radiation

- Chapter 2 Photographic Equipment for Alternate Light Source Imaging

- Chapter 3 UV and Narrowband Visible Light Imaging

- Chapter 4 Digital Infrared Photography

- Chapter 5 Polarized Light Photography

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Alternate Light Source Imaging by Norman Marin,Jeffrey Buszka in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Forensic Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.