- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

History of US Economy Since World War II

About this book

A collection of articles covering the economic history of the US over the last 50 years. It is selective in its coverage of important issues not often treated historically, such as the economics of medical care and the educational system.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

StoriaSubtopic

Storia mondialeCHAPTER VII

Government Growth and Government as Manager

52. The Inevitability of Government Growth

Harold G. Vatter and John F. Walker

Excerpted from The Inevitability of Government Growth by Harold G. Vatter and John F. Walker. Copyright © 1985 Columbia University Press. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. Harold G. Vatter is professor emeritus and John F. Walker is professor of economics at Portland State University.

One hundred years ago a conservative German economist, Adolf Wagner, observed that the government had been growing faster than the private sector of the economy for much of the nineteenth century. He predicted that the pattern he observed for that century would continue in the industrial nations as long as they continued to grow. This prediction that the government will grow faster than the rest of the economy has been tested many times in many countries and has always proved correct. Economists now call it Wagner’s Law. Since it has been proven correct for many countries for more than a century and has never been found incorrect, it is probably the most accurate economic prediction ever made.

The Era of Big Government

Americans have always thought of big government in peacetime as an ogre to be exorcised if at all possible. But in spite of ourselves the creature seems to become ever more distended. The federal government, which is deemed out of touch with the grassroots, is particularly derided. Hence it is sporadically vowed with renewed vehemence that the government must be cut down to size at all costs.

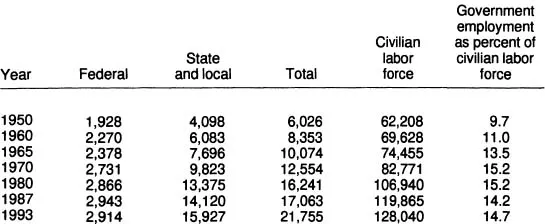

Table 52.1

Government Civilian Employment, Selected Years, 1950–93

(thousands)

(thousands)

Sources: Economic Report of the President, 1988, pp. 284—97. Economic Report of the President, 1994, pp. 306–19.

A whole series of presidents have taken this vow. President Carter liked to discuss an era of governmental limits and asserted that government could not do everything. President Reagan unabashedly called for a reduction in the share of the economy going to the government. That is, these presidents have asserted that Wagner’s Law must and can come to an end. But they have also advocated economic growth and a further expansion of the benefits of the modern industrial economy, which they mistakenly associate with an end to the growth of government.

After 1970 the growth rate of government employment slowed. For six years all government civilian employment hovered about its historic peak of some 16 million people. Federal employment, always much smaller than combined state and local employment, is only slightly higher today than it was in 1970. Only the state and local work force has continued its invincible upward creep, although it too has distinctly slowed. Thus on balance it begins to look, at least on the basis of the employment criterion, as though the first phase of a stoppage may have been completed. These changes may be seen in Table 52.1 for government employment.

The concomitant battle of the government cutters to call a halt on the expenditures front also seems to have been victorious—at least in the relative sense of government spending as a share of total economic activity. Government purchases of goods and services amounted to about 21.5 percent of GNP in 1970 and 20.4 percent in 1987. Voila!

Modern conservative economic advisers describe the government as an institution hampering growth and taking resources away from the “productive” private sector. Wagner also divides the economy into private and public sectors, but Wagner, an adviser to Otto von Bismarck, did not see government as unproductive.

There is more to the size of government than nominal public spending and employment, as every regulated person or group, every lobbyist, every tax accountant, every military contractor, every subsidized farmer knows full well. We have connected government and private employment in many ways. For example, when we decide to build a Star Wars defense system, we do not need more soldiers, we need more physicists, technicians, and assemblers in the laboratories and factories of the private sector. But surely government causes those nominally private jobs.

Budget and employment measures do not get at the true influence of the government on the economy. There is another criterion for measuring the size or influence of the government in the economy and society. The criterion is administrative involvement in the economic and social process. We find that the growth of administrative involvement is the basic change in the character of Wagner’s Law that has developed in the twentieth century. Such involvement encompasses a wide range of government guidance programs, but they usually employ very few people and often do not cost very much money. However, they exert sufficient government influence over the way the so-called private sector behaves to eliminate the notion of truly “private” activities in many of our industries and in the economy and society at large.

The Keynesian perception of unemployment equilibrium that so mightily contributed to the establishment of the mixed economy in the United States and elsewhere in the 1930s is a phenomenon of the highest import for anticipating the government’s future role. As crystallized in the Employment Act of 1946, a powerful new social consensus assigned to government permanent responsibility for overcoming the failure of the market to provide sustained high employment. Many of the heterogeneous social and political components from that consensus were quite unaware that anything had gone awry with the private investment growth mechanism. What was perceived was only the immediate malaise.

The experience since the end of World War II is that the U.S. economy grows at about 4 percent per year when government spending grows rapidly and at only a little more than 2 percent per year when government spending grows slowly. This is illustrated in Table 52.2.

Table 52.2

Average Annual Compound Percentage Growth Rates, GNP and Government Purchases (1982 dollars)

Period | GNP/GDP | Government purchases |

1947–53 | 5.3 | 15.1 |

1953–60 | 2.0 | 0.5 |

1961–68 | 4.5 | 5.0 |

1969–83 | 2.2 | 0.6 |

1983–87 | 3.9 | 4.5 |

1987–93 | 2.1 | 1.1 |

Source: Calculated from Economic Report of the President, 1988, pp. 250–51, using centered three-year averages; Economic Report of the President, 1994, pp. 270–71.

Although there have been many prophets forecasting extensive periods of rapid economic growth with little or no government growth, we have not had such a period since about 1910. We have every reason to believe that such a period is impossible in the contemporary U.S. economy. Presidents, presidential candidates, the U.S. Congress, and the aggregate of state and local government officials that push for significant reductions in public spending are advocating deliberate sabotage of the material betterment that Americans so dearly and proudly cherish.

The public decision to discard laissez-faire over a half century ago in the United States, and the subsequent rise of big government, was an irreversible change. That upheaval created in the form of the “mixed economy” a partial but growing fusion of the market system with a greatly enlarged government sector. Big government changed the composition of total demand. It cut private household consumption from laissez-faire’s three-fourths to about two-thirds of total spending. Already by the end of the Great Depression government purchases had permanently superseded gross business investment in plant and equipment, making it the second largest of the four great spending streams.

Business investment developments reveal in microcosm much of the history of business-government manipulative involvement. Still erroneously considered an almost sacred source of economic growth and productivity rise, business succeeded in making “private” investment the spoiled child of public policy. Public mortgage risk underwriting, sympathetic interest rate policies, liberal depreciation tax privileges, investment tax credits, and corporate bailouts have been easily wrung from many a willing Congress and Federal Reserve Bank, allaying the earlier business fear of big government’s “interference.” The interference was so benign that, unlike household consumption of private market products, the share of strategic plant and equipment investment in GNP has persistently remained as high as it was in the laissez-faire 1920s.

President Reagan and Congressman Jack Kemp were associated with a relatively new group of semi-Keynesian conservatives called supply-side economists. This group has a hoary faith in the power of private investment spending on capital goods to lead an economic expansion—hence, all the public inducements and tax subsidies, especially to “private” investment in business plant and equipment.

But the history of such investment belies these alleged powers. Technological advance has made improved capital goods so productive that the growth of expenditures on them typically creates more capacity to supply additional products than demand for those additional products. So unless the net production of such investment goods is restrained to its customary proportions, 10 to 11 percent of total demand, depressing excess capacity results. Capital saving investment has killed itself off as a demand growth stimulus by its own capacity-raising successes.

It is distressing to the supply-siders but most instructive to the rest of us to realize, for example, that from 1968 to 1985 real gross business investment spending on producers’ durable equipment rose at a vigorous 4.33 percent a year, yet GNP expanded at only a sickly 2.5 percent a year. High (publicly subsidized) investment has not, therefore, despite the conventional wisdom of the supply-siders and their followers, been necessarily connected with high growth rates of total product. Instead, we had in that distressingly long period under-utilized capacity and relatively slow growth.

It is essential to appreciate these limitations of the growth role of investment, not only to dispel supply-side illusions, but more important, to grasp the vital notion that autonomously rising government expenditures are in the long run the only escape from the contemporary economic stagnation malaise. Yet so overwhelming is the public denial of the usefulness of public spending that almost no one dares express the notion that we need it to maintain economic growth—even the minority who is conscious of it.

Application of the principle that the economy needs growing demand to buy the growing supply that investment creates yields the bottom line for the future growth of government spending: It must rise approximately as fast as GNP (as it did from 1983 to 1988 under the stimulus of large, unwanted federal government deficits). In the past it has grown faster. Between 1968 and the recession trough of 1982 government spending stopped growing approximately as fast as GNP, explaining the long-run slowdown in GNP growth. Whatever the future growth rate of government spending, it will be a policy decision.

But in the future we can add to government’s spending growth the element of pervasive public involvement in much, if not most, of the economy’s activities. This additional element of public participation will assure total government’s continued relative growth.

Some of what we call public involvement in the economy is no doubt represented in the expenditure or employment totals. There is a certain overlap. But very substantial kinds of public intervention bear little connection with either the budget or the number of employees in the pertinent agencies. For example, the government performs a vast oversight and assistance role in the activities of our financial institutions and related financial markets. But its great influence on that sector is insufficiently expressed in the number of people working for the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Federal Reserve Banks, the Farm Credit Administration, the Home Loan Bank Board, or the section of the Internal Revenue Service that indulges “financially troubled” banks.

53. Real Public-Sector Employment Growth, Wagner’s Law, and Economic Growth in the United States

Harold G. Vatter and John F. Walker

Reprinted with permission of the original publishers, Foundation Journal Public Finance, The Hague, from Public Finance/Finances Publiques 41 (1986), pp. 116–38. Harold G. Vatter is professor emeritus and John F. Walker is professor of economics at Portland State University.

John Musgrave’s estimates of the federal government’s constant dollar gross stock of fixed capital (structures and equipment) show that the magnitude jumped from 2.4 percent of all fixed nonresidential gross capital stock in 1929 to 13.5 percent in 1949 but thereafter fell steadily to only 8.8 percent in 1979. This is hardly in accord with the constancy of federal employment relative to the total civilian labor force after 1949 or with the many pecuniary measures of federal government growth after 1949. Furthermore, the federal percentage jump from 1929 to 1949 reflects in large part the special circumstance that the private capital stock grew only 7 percent in that twenty years. If we turn to the state and local stock, the trend record is similar; the percentage is 25 in 1929, jumps to 41 in 1939, and rises only to 44 in the next four decades. This conflicts with everything we know about the rise in the relative importance of state and local government, on any measure, after World War II. Therefore, we conclude that the use of the public capital stock is an inappropriate criterion for appraising the relative growth of government.

This paper is concerned with the United States and apprises the growth of government therein, particularly since 1929, using employment mainly, but not exclusively, as the measure. It is thus concerned with the long-run record of real human resources engaged. The federal and the state and local (S&L) levels are also disaggregated. The appraisal furthermore treats the size and character of the government sector as it impinges upon economic growth.

Despite the commendable work of Morris Beck and others on real public-sector growth, an expenditure approach is seriously flawed in its capacity to show trends in absolute, and even relative, real resource absorption. This is readily acknowledged by Beck et al. All-government expenditure and purchase totals suffer from the distressing effort to form a single separate package out of the federal and S&L totals, and then to sum the two into one aggregate encompassing: (1) purchases, mostly of goods, from the private sector; (2) purchases of the services of government employees; and (3) transfer payments to persons, net grants-in-aid from the federal to the S&L governments (and net interest paid). What such a heroic summation process can show, and what it signifies regarding impact, is not easy to discern. The procedure is beset with much more precarious pitfalls than GNP calculation because there is only a handful of components. Furthermore, conversion from nominal to real expenditure aggregates requires selection of the appropriate deflator. A word of our own on this seems in order.

One difficulty would arise from the selection of a deflator for government purchase of goods. When the government contracts to purchase eight hundred fighters at $17 million apiece, no reasonable person believes this stipulates that the government will either buy eight hundred fighters or pay $17 million apiece for however many it eventually buys. To describe correctly the prices government pays and the quantities it receives, we need actual payments ma...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- I. The Economy at Midcentury

- II. Highlights of Change in the Postwar Era

- III. Changes in the Structure of the Economy

- IV. The Evolution of the Business Sector

- V. The Labor Force and Labor Organization

- VI. Changing Material Conditions and the Quality of Life

- VII. Government Growth and Government as Manager

- VIII. The Financial Superstructure, Prices, and Monetary Policy

- IX. The Foreign Balance and Foreign Economic Policy

- X. The Long Stagnation

- Index

- About the Editors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access History of US Economy Since World War II by John F. Walker,Harold G. Vatter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia mondiale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.