![]()

1

Introduction

Why Milk?

On the “Specialness” of Milk

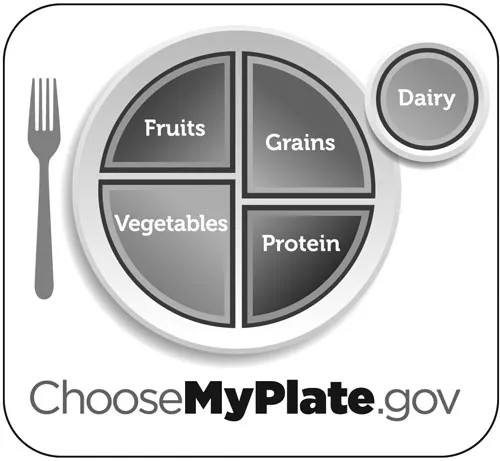

Growing up in the United States most of us have been told: “Drink your milk!” If we stubbornly refuse or ask why, we are admonished that drinking milk will “help us grow” or “grow strong bones.” These are ubiquitous messages in the U.S. and many other countries, especially those with well-established dairy industries, and increasingly in countries where milk traditionally has not been produced or consumed. Milk is endorsed by the U.S. government, appearing in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and its more familiar visual representation, “MyPlate,” which recommends that all Americans consume two to three servings of milk or dairy products each day. It appears as a strange white mustache on celebrities in print advertisements and is ubiquitous in school cafeterias. It probably was featured on posters in your elementary classroom and in whatever nutrition education you received in school. Perhaps you drink multiple glasses of milk daily, or despise the taste and avoid it like the plague, but regardless of their actual milk consumption practices, most Americans “know” that milk is something they “should” consume on a daily basis.

Where did this idea and other beliefs related to milk come from? What is milk, and why is it considered such an important food in the U.S. and in many other countries? In this book I will be concerned with these questions and several others. Why do some people get sick when they drink milk while others experience no problems whatsoever? What happens if you don’t “drink your milk”? Does milk help you grow? What role does milk play in the diet and economies of societies around the world? What is the cultural significance of milk in the U.S.? Is milk “special” or “unique” in ways that set it apart from other foods?

In this book I will explore the diverse meanings of milk and the factors that influence milk consumption. The emphasis will be on the United States, but I will also consider how milk is understood and consumed in other contexts, particularly in India, where I have conducted long-term research, and in China, which has the fastest growing dairy industry in the world. Unless otherwise noted, milk will refer specifically to cows’ milk, which is the type of milk most widely produced and consumed in the world today.1

Milk is somewhat different from other foods in your diet. First, it is the only food that is produced by mammals to be consumed by members of the same species. Second, milk is consumed by infant mammals only—juveniles and adults do not drink milk. Indeed it has been shaped during the evolutionary history of each mammalian species to match the unique developmental needs of its infants. Milk contains numerous compounds that promote infant growth, development, and immune function. Many humans are unusual among mammals in that they consume the milk of different species and consume it well beyond the age at which they would be weaned from nursing. Thus milk has some qualities not shared by other foods, and, as a result, possibly some special physiological effects on those humans who consume it.

This “specialness” of milk is manifest in a variety of ways. In the United States and many other countries, milk is featured in food-based dietary guidelines such as MyPlate, where dairy constitutes a unique “food group.” As Figure 1.1 shows, the other groups are just that: multiple foods fall within the “fruits,” “vegetables,” or “protein” groups. Furthermore, despite the fact that milk is also a rich source of protein, milk and the products made from it are singled out as a separate group, with two to three servings as the daily recommendation. Note that in the MyPlate graphic, the emphasis is on drinking milk rather than eating it in a solid form on the plate (e.g., as cheese).

Figure 1.1 MyPlate, the pictorial representation of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (Source: www.choosemyplate.gov).

Milk is also privileged in U.S. government feeding programs such as public school breakfast and lunch programs. In such programs, as well as those in private schools or preschools, milk purchases are reimbursed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). It is also a key component of the Special Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which was initially authorized in 1974 to subsidize nutrient-rich foods for pregnant or breastfeeding women, and infants and children up to 5 years of age. Fluid milk (4–6 gallons per month), yogurt, and cheese are among the foods that are subsidized. Across the globe school milk programs are common, and milk is often included in international food donation programs. Thus there is a sense that milk is an especially valuable food, even “essential” to the diet, particularly of children, and that the absence of milk in the diet is cause for concern.

However, another way in which milk is “special” has to do with the sugar in it. Lactose is a sugar found only in milk (hence the term “sweet milk” for fresh milk, as opposed to various fermented “sour” forms of milk, although lactose itself does not taste very sweet), and there is well-documented genetic variation among human populations with respect to the ability to digest this sugar throughout life, with only a minority of humans having this capability. Virtually all humans produce the enzyme necessary to digest this sugar when they are infants, but most stop producing it sometime during childhood such that lactose ingestion during adulthood often results in a variety of gastrointestinal complaints, which are collectively termed lactose intolerance.

Historically there has been pronounced cultural variation in the valuation of milk, with some groups idealizing this food and others emphatically disdaining it. These divergent views of milk have tended to correlate with variation in milk digestion. Those populations with the genetic trait allowing lactose digestion throughout life also likely to be those who strongly favored milk. This range of views about milk has been undermined by efforts to globalize milk production and consumption, and more and more countries have jumped on the milk bandwagon despite quite distinct subsistence, culinary, and evolutionary histories.

My goal in this book is to provide insight into a food that can be considered “special” in several respects, and one that is currently widely believed to be essential to human diets. First and foremost it is important to have a good understanding of what milk is as a food. In later chapters I will take up the question of what kinds of biological effects milk has on humans, focusing on variation of milk digestion and whether milk has growth-promoting effects on children. I will also touch on some of the current controversies surrounding milk consumption among adults (e.g., milk’s link to bone density or chronic disease). Framing the discussion of the biological and epidemiological evidence used to evaluate these linkages will be the cultural context that shapes how and why these questions are asked, how the results of this research resonate with or shape our beliefs about milk as a food, and how they are used in milk advertising and the formulation of dietary policies in different countries.

This particular food commodity is of interest in its own right as both a biological and a cultural product, but as a food it can also provide a lens that reveals underlying socio-cultural processes. Milk can be used to illustrate beliefs about what constitutes a “normal” diet, both in the sense of what is the “norm”—i.e., the most common—or what is “normative”—i.e., the ideal diet. Similarly, people hold beliefs about “biological normalcy,” i.e., the characteristics most healthy bodies have or should have. Insofar as these beliefs inform interpretations of other diets or bodies and judge them to be inferior or lacking in some respect, this study of milk yields insights into what I call ethno-biocentrism. This term refers to how other people’s bodies or behavior are interpreted in relation to one’s own body and culture. Not surprisingly, one’s own is often considered “better” or “normal,” while others are viewed as “abnormal,” pathological, or somehow “wrong.”

Milk also serves as a particularly illustrative example of how political and economic processes inform dietary policies and nutrition education. Since their original development, milk has been part of dietary recommendations in the U.S., and milk’s status as a “good” or even “essential” food has been largely uncontested. This is in part due to a strong and active dairy lobby that ensures that its product is featured prominently in government-sanctioned recommendations (Herman 2010; Nestle 2002). While it may seem that milk would be a poor candidate for global trade, given its tendency toward rapid spoilage, technological innovations and the drive to expand markets for this commodity (and the technology that supports it) have resulted in an unprecedented movement of milk around the world. Thus milk can be used as a study in the globalization of food and Western culture.

A Biocultural Perspective on Milk

To fully consider these questions we need a biocultural approach, one that appreciates milk as both a biological substance with specific physiological effects on the body, and as a food that is part of complex global and local agricultural economies and that has an array of cultural meanings across and within societies. Biocultural approaches draw on the holistic tradition of anthropology, a discipline that seeks to understand the “whole” of humanity. Anthropology includes the study of human evolution, human behavior in the past (archaeology), contemporary cultural variation, and language and linguistic diversity. Each of these aspects of anthropology can contribute something to our understanding of milk, as our experiences with milk are shaped by cultural, political, economic, and evolutionary processes and are expressed through verbal and visual communication.

Of the many perspectives that anthropology can offer any aspect of human behavior, in this book I will generally use approaches from cultural and biological anthropology, with less emphasis on archaeological or linguistic perspectives. Biological anthropologists seek to understand how humans are biologically similar to or different from other organisms, and why humans have their particular biological characteristics (e.g., a large brain, or an anatomy built for bipedalism). To do so they use the principle that unites all of the life sciences—evolution. Evolutionary theory, which dates back to Charles Darwin in the mid-19th century, has provided us with remarkable insights into the biology of all living (and extinct) species, including our own, Homo sapiens. It provides a way to understand variation between and within species, over time and in the present. One of Darwin’s main contributions was to demonstrate that the process of natural selection could account for some of this variation. Natural selection simply refers to the fact that individuals vary, variation is heritable (i.e., passed from parents to offspring via their DNA), and that individuals with characteristics that help them survive and/or reproduce in the context of the environment in which they live (which contains predators, food sources, and other living and physical features) will have more offspring than others without those traits. Since these traits are inherited, more individuals in the next generation will have these traits, and over time they should become typical of the population or whole species. Characteristics that enhance survival and reproduction are called adaptations or adaptive traits. We expect organisms to have adaptations for getting food, escaping predators, staying warm/keeping cool, coping with pathogens, and so on. In the case of milk, the qu...