I

Policy questions about avoiding climate change involve decisions under, at best, uncertainty. Our difficulty is that we don’t know the likely degree of climate change, nor its cost. But these limitations on our knowledge may seem no different than those infecting many of the decisions we have to make on a daily basis.

I am 65 years old and have no long-term care insurance. Should I buy some? It is a question I have asked myself on and off for the last 10 years, but my decision remains unresolved. It is a hard decision to make, if only for psychological reasons. A desire for a quick death, or alternatively, immortality, clouds the decision. Bracketing psychological considerations, should I buy the insurance? As with all insurance, it is a decision under uncertainty. But it is one for which statistical data is available. There are enough data points that I can fine grain the data base as much as I want to derive a sample that is very much like me, even if it is not identical with me. Of course how much to fine grain is a matter of discretion, and one that may not matter too much depending on how little doing so changes the distribution of the results. Those results will give me a figure for the probability that I will need to use the policy at some point in future. What is much harder to decide on is this: what the value of the insurance is in dollars on the day I pay the premium. The benefit is in dollars in the future (if a payout is triggered), unless I have a stroke before the day on which the policy becomes effective. What discount rate should I apply to normalize the difference between the two? Suppose I pay $10,000 in a lump sum now and use the policy 10 years from now for a year, garnering $20,000 in benefits after which I die. The present value of that benefit is not $20,000 but the amount of capital that would yield $20,000 in 10 years if invested. How much that is depends on what I assume the rate of return to be. The present value (PV$) of $20,000 10 years from now is a function of the (inflation adjusted) interest rates (IR%):

| IR% | PV$ |

| 4 | 13,500 |

| 5 | 12,000 |

| 6 | 11,000 |

| 7 | 10,000 |

Suppose I use the average rate of return on my retirement portfolio as a guide. Then the worth of the policy today is a function of the net present value of the payout for each year and the probability that I will use it in that year.

Are we then done? Not quite. There are additional considerations that may be relevant to how much to discount the value of a future payout. So far, all we have considered is essentially the inflation-adjusted opportunity cost of spending money on a premium instead of investing it. But the value of a dollar now as opposed to in the future is also a function of technology. Technological advances reduce the cost of living. So, $20,000 in 10 years may buy more than it does now, despite the effects of inflation. If I want to buy care worth $20,000 in 10 years based on current technology, on this consideration, I can plan to pay less for the same care in the future in real dollars. So I can further discount those dollars in the present. Finally, there is this to consider: maybe a dollar spent now is worth more to me than a dollar spent 10 years from now.

There is a good reason to ignore this last consideration, if only for my own (long-term) good. Money tends to burn a hole in my pocket and hence I tend to overdiscount the value of future money. But there other reasons that look more legitimate. I value life more now than I expect to value it in the future because I am younger and more vibrant now. I, literally, get more out of life. It is not that money spent caring for me in the future will be worth less than money spent on (say) wine and music now but that, all other things being equal, the value to me of a dollar then and now will be different. Still other reasons are not obviously illegitimate but not obviously legitimate either. I care about me now more than I care about the me that will be in the future. It is the kind of sentiment that tempts me not to go to the gym and diet. No doubt a life led now without excess will yield benefits to my future self, but I find it hard not to discount the value of my future self relative to my self now.

These complications notwithstanding, making such a decision under uncertainty for an individual is reasonably straightforward. And it might seem that extending the approach to collective decision making ought to be no less straightforward. That is certainly true if we stick to one generation. But as soon as the collective decision involves more than one generation things get more complicated.

Deciding whether or not to buy insurance involves two very distinct components: one is epistemic. That implicates both the matter of setting a value for the likelihood of particular outcomes and some features that go into setting a value on the discount rate, like the rate of return on capital and the rate of technological innovation. But the other component is purely valuational, as when I am forced to decide how much to care about the future as opposed to the present.

When we think of decision making across generations, the epistemic challenge does not change in kind but does in complexity. Time is our enemy here. The further our horizon of concern, the less confident we can be about our assignment of probabilities. It is one thing to extrapolate from a subset of the population now to another subset of the population now, and quite another thing to do the same thing across time and more so, the larger the swath of time. (For example, think how much both life expectancy and technology have changed in the last 100 years.) But when it comes to matters of valuation, a much deeper issue intrudes. My quandary about whether or not to buy long-term care insurance was a conflict between my interests now and my interests in the future. But when it comes to climate change, the tradeoff between interests is between us now and others in the future. That seems to turn a calculus of self-interest into a matter of altruism.

Still, to the extent that we think of our government as representing our collective self-interest, not only in time but across time, maybe the calculus of self-interest can be preserved. If we think of each generation as benefiting from the sacrifices of the previous generation, there is still always a temptation for each of us, as individuals, to break with the implicit compact between generations. We harvest the slow growing trees they planted, but fail to replant new ones. We benefit from the practical results of their costly theoretical research, but fail to fund such ongoing research at an appropriate level. We cross the bridges designed to last 100 years that they built, but fail to renew them as they become worn down. Yet knowing we are subject to such inclinations, we rely on our government to act on behalf of our better selves. We look to them to act in our self-interest where the “our” reaches out across generations. But be that as it may, such government action still has to depend on citizen support in the here and now and, whether based on self-interest or altruism, such support depends on our perception of how things are. So when a government acts in a way that may seem to be in the collective interest, it can’t avoid dealing with how individuals see things.

II

I used to smoke and I enjoyed doing so very much. I gave up after my doctor told me it might kill me. “Might” was enough to convince me that the pleasure did not outweigh the risks. For all I know it may have turned out that his warnings were misplaced. Maybe the correlation between smoking and disease will turn out to be spurious – the result of a common cause. But the uncertainty gets swamped out by the costs of being wrong. The cost of death to me is high. High enough that even if there is only a small chance of my doctor being right, I want to avoid it. And the price of avoiding it, foregoing the pleasure, pales in comparison to that. Assume my actions are rational when it comes to smoking. What prevents their extension to averting climate change? One difference is this: the statistical data on the risks of smoking are well established in a way that is observer independent. They are a function of the frequency of death among smokers as compared to non-smokers. Of course we have to control for all sorts of other things, but all other things being equal, “the effect of smoking on the chance of dying is similar to the effect of adding 5 to 10 years of age” (Woloshin et al. 2008, 845). Moreover, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that on average, smoking reduces life expectancy by between 13 and 14 years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2002). Yet when it comes to making an individual decision about whether to smoke or not, what matters is not what the observer independent risk is, but on what the perceived risk by the individual is. That subjective perception of risk (and with it cost) is what matters when it comes to making a decision based on the costs and benefits. So, even if what I will call the objective risk of not acting to avoid climate change might be the same as the objective risk of continuing to smoke, the perception of risk, the subjective risk, might be different. And indeed, the literature on risk perception gives ample reason to think that it will be different.

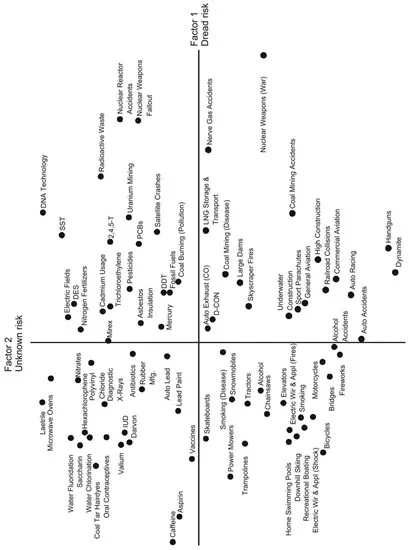

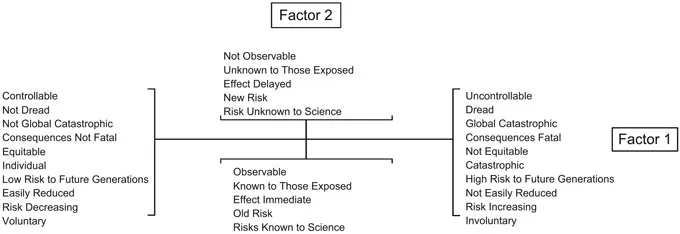

Beginning in 1978, Fischhoff et al. (1978) used factor analysis in an attempt to study how hazard is perceived. Their results support the view that much more is going on than a simple estimate of probabilistic frequencies. Instead, the ordering of risk for different activities is a function of two separate dimensions of perception, broadly: unfamiliarity and dread. The first provides an ordering in terms of risks that are perceived as:

voluntary, immediate, known, controllable and old versus involuntary, delayed, unknown, uncontrollable, and new.

While the second is along a dimension between of risks perceived as:

not certain to be fatal, common, and chronic versus certain to be fatal, dreadful, and catastrophic.

This provides for a distribution over hazards of the two-dimensional space shown in Figures 1.1a and b.

In this two dimensional space, the lower left quadrant represents the lowest area of perceived risk. Notice that smoking is located in that quadrant. Its relative position compared to other hazards (like satellite crashes) reflects how at variance subjective judgments of risk are as compared to an objective ordering.

That said, where we act to diminish risk, our risk-avoidance actions are not necessarily reflected in our ordering of risk perception. For example, people are more likely to stop smoking than flying, even if they (incorrectly) rate the latter as riskier than the former. But that should not be surprising, because risk avoidance is not just a function of risk perception; other considerations come into play as well. After all, the cost and inconvenience of foregoing air travel is high.

Is the difference between my attitude to risk avoidance in climate change as compared smoking that I assess the hazard as lower, or is it that here too other considerations (like the perceived cost and inconvenience of avoiding the risk of climate change) are in play? Of course, these are not mutually exclusive, but even if we bracket such considerations for now, a salient complication is that we need to distinguish between consideration of risk avoidance of climate change as a question about me or as a collective question. The latter is surely the interesting of the two. But then we are comparing how important I think it is to act individually to avoid smoking as compared to how important I think it is to act collectively to avoid climate change. But if we focus on risk perception, the two are still comparable, for what we are interested in comparing is subjective risk perception. And that is still an individual affair whether the subject involves individual or collective action or choice.

FIGURES 1.1a, b The Perception of Hazard (Slovic et al. 1980)

If we apply the components of the two dimensional model of risk perception, where should we expect the risk of climate change to fall in that space? Swim et al. (2009) suggest that:

To the extent that individuals conceive of climate change as a simple and gradual change from current to future values on variables such as average temperatures and precipitation, or the frequency or intensity of specific events such as freezes, hurricanes, or tornadoes, the risks posed by climate change would appear to be well-known and, at least in principle, controllable and therefore not dreaded.

(Swim et al. 2009, 40–41)

But of course the risks of climate change are distributed over different outcomes, ranging from the relatively benign to the very bad. “Dread” is more likely when we focus on the very bad rather than the benign or even a weighted average of the two. Which do we focus on and which should we focus on? Smoking has many damaging effects on the body, but not all of them are fatal. For example, smoking postmenopausal women have lower bone density compared to non-smokers as well as an increased risk for hip fracture (U.S. Department of Health and Human Service 2001).

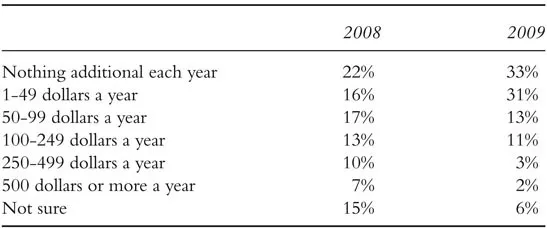

But although smoking may be bad for your health even if it does not kill you, in thinking about smoking, what we focus on are the catastrophic outcomes. And we do in other cases as well. Not wearing seat belts increases the risk of death but there are consequences less extreme than death; seat belts also lower the chances of injury. Yet while we focus on the former not the latter when it comes to seat belts, we don’t seem to do so that when it comes to climate risk. A good way to gauge this is by assessing willingness to pay for policies that reduce carbon output. For example, in a poll for Brookings, Rabe and Borick (2011) asked respondents what they would be willing to pay annually for more renewable energy to be produced (see Table 1.1). That seems to reflect anything but an attitude of serious concern, even if we bracket those who are unwilling to pay anything at all as skeptical that climate change is real.

TABLE 1.1 Willingness to Pay for Renewable Energy (Rabe et al. 2011)

What is going on? On one dimension of risk, climate change ought to count as worse than smoking or not wearing seat belts. It is less voluntary, immediate, known, controllable, and old, rather than involuntary, delayed, unknown, uncontrollable, and new. Is the issue the second dimension of risk perception? Is it because it is treated as common and chronic rather than certain to be fatal, dreadful, and catastrophic? But if so why? This is just a restatement of the issue. Climate change has dreadful worst case outcomes even if they are not certain. Why do we not focus on them then in the way that we do with wearing seat belts whose worst case outcomes are also uncertain?

Perhaps the difference hinges on something beyond the two-dimensional model: namely, the role of experience of small probability events as opposed to analytic inferences about them. Experience amplifies risk judgments beyond their objective consequences (see for example, Slovic et al. 1986). An important difference between not wearing seat belts and climate change is that we have the opportunity to vicariously experience the consequences of the first but not the second. Think only of how we feel as we drive past the scene of a serious car crash, or even see a severely damaged car on a flatbed tow truck. (The same is true when we hear of or read about someone dying of lung cancer.) On the other hand, by and large, the (catastrophic) consequences of climate change are only available to us in abstract terms.

Abstraction enters into the picture in another way as well. The potential damage of climate change will not only fail to affect me directly, but it won’t even affect my grandchildren wit...