I fell into conversation with a Frenchman I sat next to last night at dinner, and I just couldn't resist getting onto education, because the French have such different views on education – they cannot understand how we can possibly do what we do – how we can bear to send our children away: they should be coming in to us every night and talking to us every night, how we mustn't lose touch with them, and how vital it is to see them every day. I totally disagree – I think it's the making of them, this sending them away. And, you know, I can see what happens, I can see them every three weeks – it's not a drama, really.

(A mother of one of the 8-year-old new boarders talking to camera in Colin Luke's 1994 film The Making of Them)

Key points of chapter

- Psychology professionals have been slow to acknowledge that the British culture of sending young children to boarding school has an impact on psychological wellbeing.

- Although unsupported by any theory of child development, the practice is still seen in some quarters as a desirable way to educate children.

- A body of literature on this important topic has been built up over the last 20 years.

Setting the scene

This book aims to help psychotherapists, counsellors and other mental health workers to develop a therapeutic approach to adult clients who were sent to boarding school as young children. This first chapter gives background information to set the scene for these therapeutic interventions.

We are writing early on in the twenty-first century. Over the previous century enormous strides were made in the field of children's rights; psychology grew from small beginnings to become a major influence in society. Many theories of child development evolved from a number of perspectives – educational, cognitive, humanistic, maturational, behavioural, psychodynamic and so on. But nowhere can we find a single theory of child development that underpins or backs up the British practice of sending young children – aged 8 or sometimes younger – away from their families to reside in educational institutions for approximately 75 percent of each year.

Most people would accept that the fundamental role of parents is to love and protect their children while gradually nurturing their independence, so that by the time they reach adulthood, they can begin to make their own way in the world. This normally involves a step-by-step and very gradual process towards increasing maturity and appropriate autonomy.

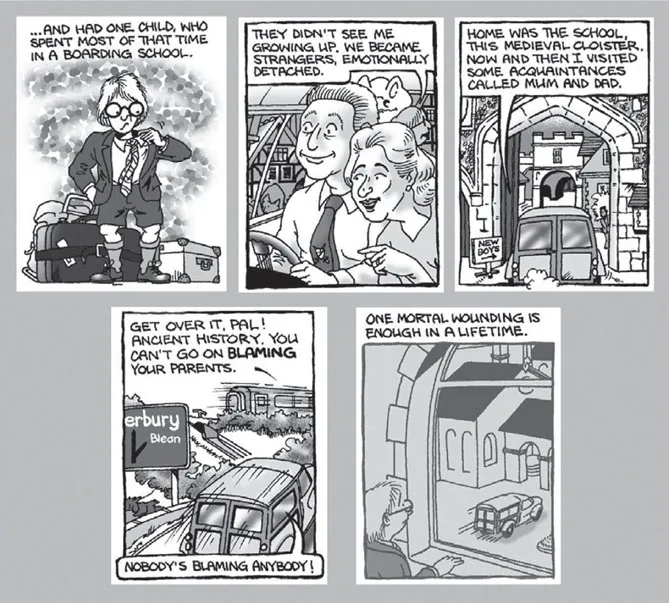

And yet there is – in a manner of speaking – a tribe of people, living mostly in deepest Britain, who see things differently and have strange customs. They adhere to a socialisation doctrine perfected in mid-Victorian England, whereby the normal process of child development is interrupted by a dramatic and drastic change in which family attachments are deliberately broken. The practice appears cruel to those outside this tribe, as it does at the time to the children of the tribe, and it can leave deep emotional scars. Unlike such abhorrent practices as female genital mutilation, its scars are not obvious to the human eye and do not normally involve – anymore – bodily harm. But they are real scars nevertheless which can have a profoundly negative effect in adult life.

The tragedy is compounded because this wounding has been overlooked, denied and powerfully normalised. Huge financial lobbies support the business of boarding schools, to which the UK government grants special charity status. Moreover, the tribe that supports the practice is influential and vocal, consisting of those who can afford the fees – at the time of writing some £30,000 per annum per child. It includes the traditional upper classes, the wealthy middle classes as well as the less well off but aspirant socially mobile, supplemented by rich foreign families investing in the social status such an education affords.

Their children, typically 8 year olds, discover that from day one (and for the next 10 years) they will spend 9 out of every 12 months living in a boarding school and only 3 months at home with their family. They have neither the choice, nor the right to object, and soon an internal self-monitoring process kicks in to assist the child in surviving and adapting to the inevitable. The habit of sending the children away, the process of survival and accompanying trauma are disguised and compensated by the privilege afforded by the social elitism that accompanies this form of education. Hence the title of this book.

To most modern European observers and to psychologically minded people, this antiquated practice seems like a form of child neglect – even abuse. For example, the journalist George Monbiot suggested that ‘Britain's most overt form of child abuse is mysteriously ignored’ (Monbiot, 1998). But the educational system that lies at the heart of it is a well-trodden path to privilege, power and what can appear to be a successful life. It leads from prep school (from the age of 7) to public school (from 13) and then usually to Oxbridge. This path has been travelled by countless public luminaries, including, at the time of writing, the current UK Prime Minister, the Mayor of London, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Layard, the champion of successive governments’ strategies to ‘improve access to psychological therapies’.

Herein lies one key reason why this practice is overlooked: private boarding has an almost unassailable position in the world and parents invest huge sums for their children to be part of it. It brings money into the UK, is looked up to and aspired to; insiders think it the envy of the world. A secondary vicious cycle enhances its position: the influential parents who support private boarding simultaneously opt out of the state system, which suffers in comparison and cannot compete in terms of resources. A Cinderella state system then helps further rationalise the parents’ choice for the private system, which instead of seeming outdated, presents itself as the only option for parents who ‘want to do the best for their children’.

And it does turn out many people who are ‘success stories’ – at least in the world of outer achievements. Yet, since 1990, in workshops run by the organisation Boarding School Survivors for both men and women ex-boarders seeking psychological help as adults, the overall boarding school experience has been frequently described in the following terms:

neglect – betrayal – abandonment – grief – rage – abuse – confusion – sadness – helplessness – loneliness – motherless – missing daddy – sent away – neediness – anger – suppression – denial – tears – survival.

(Selection of participants’ initial impressions on the first morning of a four-day Boarding School Survivors workshop)

It is this gap between outer and inner reality with which ex-boarders and practitioners have to engage.

The early years

How has the boarding habit escaped serious attention for so long? The first traceable mention of any problems associated with boarding education comes from the renowned Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith:

The education of boys at distant great schools, of young men at distant colleges, of young ladies in distant nunneries and boarding schools, seems in the higher ranks of society to have done crucial harm to domestic morals and thus to domestic happiness, both in France and in England … From their parents’ house they may, with propriety and advantage, go out every day to attend public schools: but let them continue to live at home.

(Smith, 1759, V1.11.13)

It was not until the First World War that the first serious psychological hypothesis about ex-boarders was made. William Halse Rivers, the ‘shell-shock’ psychiatrist, noted that many wounded officers expressed their sickness differently to the enlisted men because they were already trained to withhold their personal responses through their public school education: ‘The public schoolboy enters the army with a long course of training behind him which enables him successfully to repress, not only the expression of fear, but also the emotion itself’ (Rivers, 1918).

The next serious attempt to examine the effects of boarding from a scientific viewpoint came from post-Second World War sociology. Royston Lambert and his colleagues collected data from 12,000 boys and girls in over 60 different boarding schools – public, prep, ‘progressive’, independent and state run. Their extraordinary piece of research has more a feel of Tom Brown's Schooldays than Harry Potter and has been widely read (Lambert and Millham, 1968). Amongst his data, Lambert reported anonymous comments from a huge number of pupils about teachers who were sexually abusing pupils, for example:

Mr Tomkins is a house master and I think he is a vulgar man … he does rude things to people … please publish this to show everybody that a schoolmaster is not good at all.

He has had a warning from the headmaster about being sexy. Nobody likes him.

Keep your legs crossed if you go to coffee with Oscar, he is as bent as a clockwork orange and a right queer.

When I was trying on a uniform, this bum bandit pressed his tool right up against me.

(Lambert and Millham, 1968, pp. 272–3)

Lambert makes it clear that there were numerous similar statements and that many more disturbing comments were not published but were kept in the research files. He mentions that these revelations put pressure on research workers and made their task difficult. But there is no sense of any crime being committed or any outrage at the behaviour of the teachers for the damage that they were doing to the children in their care. The sexual abuse (not named as such) is glossed over, which probably accurately represents the prevailing attitude of the times.

Boarding on the couch

The topic was not properly discussed in a psychological perspective until 1990, when psychotherapist Nick Duffell aired the issue in an article in the Independent newspaper (Duffell, 1990) and received hundreds of confirmative letters from readers. In 1995, Duffell introduced the term ‘boarding school survivor’ to the therapy world in an article in Self and Society (Duffell, 1995). Drawing on his experience of his first decade of psychotherapy and group workshops for ex-boarders, Duffell published the first psychological exploration of the phenomenon of boarding with The Making of Them (Duffell, 2000).

As the first examination of boarding through a psychological lens, The Making of Them summarised the processes that boarding children go through and the subsequent problems encountered as adults, while proposing some avenues for therapeutic help. It was widely acclaimed, including an endorsement from the BMJ (BMJ, 2001), and enabled many ex-boarders to feel a sense of recognition. Indeed, reading the book has often been the first stage in an ongoing healing pathway for many ex-boarders.

Himself an ex-boarder and former boarding school teacher, Duffell enumerates the psychological tensions that are in force when children first leave their families to board and how they learn to survive at boarding school. He shows how this involves constructing what he calls a ‘Strategic Survival Personality (SSP)’. Once in place, this may not be so helpful when, as adults, ex-boarders attempt to navigate the waters of sexual relationships, family and particularly parenthood. The survival personality, constructed by a child, is very durable; crucially, it is very difficult for the bearer to recognise or shed, because it is so close to the identity of the self.

The book's follow-up, Wounded Leaders (Duffell, 2014a), takes a broader societal view of the boarding school system by questioning the ability of the British ex-boarding elite to govern. He argues that:

Ex-boarders hide their emotional and relational dysfunction behind a facade that usually projects confident functioning and resembles a classic national character ideal. The character ideal is one that is well known and regularly celebrated in our letters, theatre and film. Mostly, it appears as the self-effacing, conflict-avoiding, intimacy-shy, gentlemanly type so classically represented in the late 20th century by the actor Hugh Grant.

(2014a, p. 71)

This is only one facet of an SSP, however, for there is also another side to it, writes Duffell, ‘the hostile, sarcastic bullying type’ akin to Flashman and not the sort of character that anybody wants to identify with.

Duffell (2014b) believes that British politics is awash with privileged men who hide their lack of emotional maturity behind a facade of confidence that is inevitably very brittle: ‘There is, I believe, a direct link between the problems caused by boarding school experience and our domination by men who do not provide ...