![]()

Chapter 1

A world of geography – past, present and future of geography education

My opinion about geography is fun! I love geography because it is fun learning about things about the world and things I did not know about the world. I love geography it’s really interesting to learn about. I love to learn about the world and Brazil and other countries … That is the end of my opinion about geography.

Fifth class pupil, aged 11

The wonder of geography

Geography is a very popular subject. This is evident through displays and activities in classrooms, corridors and grounds of our primary schools. It is a subject that is liked by children, teachers and parents. Geography makes significant contributions to children’s learning in many dimensions. This book will support and challenge you in your professional role as teachers of geography in primary schools. It is hoped by embracing this book you will be inspired by the theories, ideas and examples found throughout the following chapters.

The book is designed to help you act on the following pillar questions:

• What do we know about children’s learning in primary geography?

• What can children do in primary geography?

• How can we make these experiences interesting and challenging for children?

• How can we provide guidance for children learning geography?

This book is not designed as a set programme, such as a geography textbook or workbook; neither does it provide a ‘solution’ to what geography should be. It is designed to help you to enable engaging learning in geography, shaped by your professional expertise. This book draws from diverse principles in teaching and learning geography that I have learned over the years through research, teaching and collaboration with many primary teachers and classes in their classrooms.

Teachers facilitate children’s learning

Teachers are very important people as you are the people who inspire children through teaching! Qualifications, specifically knowledge and skills, matter more for children’s learning than any other single factor in a school or classroom (Darling-Hammond, 2006, 2010; Cochran-Smith, 2003; Hinde et al., 2007; Haycock and Crawford, 2008). Teachers also need to know about the nature of geography and geography education in order to teach it effectively (Webster et al., 1996; Firth, 2007).

Children can participate in decisions about how and what they learn

Children are also equally important as they have so much to contribute in geography! They are natural geographers and have very important questions and ideas about how they can learn geography (Catling, 2003; Martin, 2005; Roberts, 2010; 2013a; Pike 2011b). Children are amazingly motivated to learn, when they have a role in the teaching and learning process.

Geography provides children with quality learning experiences

Learning in geography is an important and meaningful experience for children! A primary geography education provides opportunities for children to experience:

• Working through a ‘geographic lens’, to ‘acquire and use spatial and ecological perspectives to develop an informed worldview’ (Heffron and Downs, 2012).

• Enjoyable and challenging learning experiences in schools (Catling, 2003; Pike, 2013; Kitchen 2013), through enquiry-based learning about the locality and the wider world.

• Preparation for life in their future, as members of communities (Bednar, 2010), providing children with the essential ‘geographic advantage’ (Hanson, 2004; GA, 2009).

This book is about making geography interesting and engaging for children, teachers and parents, as will be shown in the case studies and photographs throughout. It is not about ‘surface’ learning or about doing ‘something different’ as a treat after learning in a ‘proper’ lesson from a textbook; the experiences outlined in the book are the learning! Little of the learning in this book involves expensive resources; it relies on what is already in schools: the school, the local environment, digital technologies, atlases and globes, as can be seen in Figure 1.1. However, there are fantastic resources for primary geography, such as photograph packs, constructions toys, mascots, maps and the locality, that can be bought instead of, or as well as, textbooks and workbooks. This may take planning and effort but it is easily achieved over time, as outlined in Chapter 10.

Learning in primary geography

The practices of geography education in different countries are fascinating, and there are many views about how and what should be taught in schools in geography. This argument was very apparent in the curriculum changes in England and continues to be debated in the United States, as well as other countries. In Ireland, the debate over a subject or skills-based curriculum is very current. Basically, the perspectives are about the two main dimensions of learning in geography, content and approaches:

Figure 1.1 Activity in geography lessons (a) making maps, and (b) using a range of books

Perspective A: Teachers should lead learning; they know best what children should learn. Children need a broad base of knowledge in geography.

Perspective B: Children should lead learning, with the support of the teacher. Children should learn a smaller range of topics, but have the opportunity to learn at a deeper level.

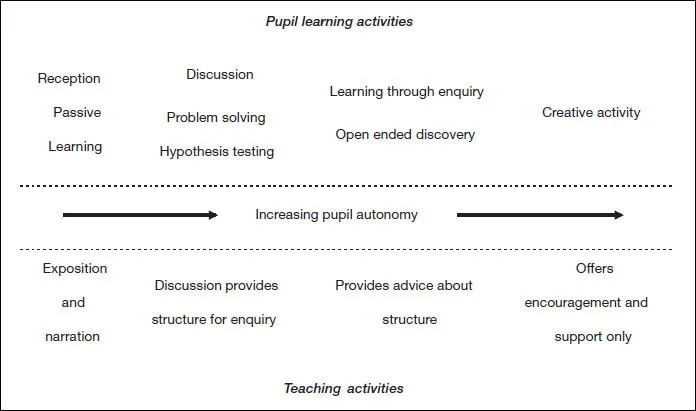

A model that captures these two arguments is outlined in Figure 1.2, showing pupilled activity on the right and teacher-led activity on the left. This model evolved from the 14–19 Schools Geography Project in the 1980s in England, which aimed to make geography more engaging for young people. However, its origins can be traced back to ideas from Dewey about traditional vs progressive education (1938/2007). Naish’s model shows how a range of learning activities can take place in geography lessons, led by teachers and/or children. Within this book, there is more emphasis on activity to the left of the model, that is argument B above, as this provides more meaningful, interesting and challenging opportunities. So, we can use activity from across this continuum. For example, there are times when we simply tell children new ideas and concepts. However, learning of such new ideas and concepts works best when it emerges from learning activities.

Figure 1.2 A model for teaching and learning activity in primary geography (Naish et al., 1987)

Scanning down the list in Case Study 1.1, it is evident that those at the top are to the left of the model in Figure 1.2, while those at the bottom are to the right. Most of the activity that takes place in the schools featured in this book is to the bottom of the list and to the right of the model. In fact, when thinking about what children learn in geography, it is useful to think of geography as neither argument A nor B, but as a series of big ideas that can be taught through enquiry negotiated between children and teachers. Examples of big ideas are shown in Table 1.1, as a series of ideas that no matter what age a learner is, they will understand through good geographical experiences.

CASE STUDY 1.1 Learning through geography: all classes, St James’ National School

The children in St James’ are keen geographers; both teachers in this 2-teacher, 32 pupil school view geography as an important subject for children. The children had a range of experiences in geography, such as:

• Listening to their teachers talk about places.

• Answering questions from textbooks.

• Completing worksheets on geography topics.

• Using the internet to research about places.

• Investigating stories in the news and summarising what they found out.

• Using maps and globes to investigate places.

• Researching topics as homework, using books and the internet.

• Working in groups independently on geography topics, with the support of the teacher.

• Devising questions on topics they were about to do.

Table 1.1 Key concepts or ‘big ideas’ in geography

Leat, UK (1998) | Geography Advisors’ and Inspectors’ Network, UK (2002) | Holloway et al., UK (2003) | Leaving Certificate Geography, RoI (2006) |

Cause and effect | Bias | Space | Location |

Classification | Causation | Time | Spatial distribution |

Decision-making | Change | Place | Area association |

Development | Conflict | Scale | Inter-relationship |

Inequality | Development | Social formations | Spatial interaction |

Location | Distribution | Physical systems | Density |

Planning | Futures | Landscape and | Pattern |

Systems | Inequality | environment | Region |

| Interdependence | Change over time | |

As can be seen from the example in Case Study 1.2, ‘big ideas’ or ‘key concepts’ are significant in geography, especially in any context where there is a tradition of content leading learning in geography. In Ireland, in the past, there has been a tendency for primary teachers to get children to ‘learn off’ place names in geography (Pike, 2006; Waldron et al., 2009). This is dull for children and wastes time that could be spent thinking and being a geographer! This is not to say location knowledge is not important, and the examples above and throughout this book show how children can learn about places names and locations in the context of the topics they are learning about. These ideas are explored explicitly in Chapters 3 (on literacies) and 8 (on places). Big ideas help us to conceptualise geography and to think about how we are enabling children to make sense of the world, not to learn...