eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication

James C Mccroskey

This is a test

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication

James C Mccroskey

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication offers a true integration of rhetorical theory and social science approaches to public communication.

This highly successful text guides students through message planning and presentation in an easy step-by-step process. An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication provides students with a solid grounding in the rhetorical tradition and the basis for developing effective messages.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication by James C Mccroskey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part

I

______________________

______________________

______________________

Getting Started

1

______________________

______________________

______________________

A Rhetorical Tradition

In theory and in practice, rhetorical communication has a long and distinguished history. Since this book has evolved from that tradition, it is important to become familiar with some of that history to better understand how we got to where we are today. It is not possible to present a complete survey of that history within the limited space available here. Such a survey would necessitate not several chapters in a book, but several volumes. This survey, therefore, must be sketchy and selective, restricted to introducing some of the key figures and some of the significant developments in the long history of rhetorical communication. It does not include the great orators of history, although their contribution to the theory of rhetorical communication has certainly been important. Rather, attention focuses primarily on the authors whose works have influenced the development of rhetorical theory. In some cases, the influence has been positive; in others, negative. The purpose here is merely to indicate some of the highlights of the history of rhetorical communication in order to provide a better base from which to evaluate and understand the theory discussed throughout this book.

Before exploring the specifics of this historical view, it is important to place this book into perspective. There is much concern in contemporary higher education with a diversity of cultural views. The rhetorical communication perspective, while evolving from a variety of cultures, is not a multicultural one. It represents one primary cultural view of human communication. The cultural view within which the history of rhetorical communication has evolved is best described as a Greco-Roman, Judeo-Christian world view. Its primary influences have come from the Middle East, Europe, and Northern Africa. It has had its most profound impact in areas now dominated by English-speaking peoples, although it is not without influence in other parts of the world.

Manifestations of this approach to human communication are apparent in, and have a major impact on, the legal, political, and economic structures of many countries, probably most notably the United States. Thus, if one is to understand these structures, one must understand the nature of rhetorical communication within these cultures. This world view sees communication as an instrumental activity. That is, communication is seen as the way people get things done. It flourishes in environments that view freedom, liberty, justice, equality, individual responsibility, and the importance of the individual as primary values. It should be recognized from the outset, then, that the rhetorical communication perspective is not the only way significant numbers of people in the world come to view communication. It is, however, the only view that will be explored in this book.

Earliest Writings

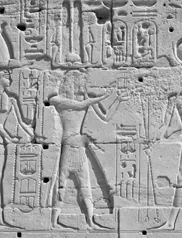

The importance of rhetorical communication has been recognized for thousands of years. The oldest essay ever discovered, written about 3000 B.C., consists of advice on how to speak effectively. This essay was inscribed on a fragment of parchment addressed to Kagemni, the eldest son of the pharaoh Huni. Similarly, the oldest extant book is a treatise on effective communication. Known as the Precepts, this book was composed in Egypt about 2675 B.C. by Ptah-Hotep. It was written for the guidance of the pharaoh’s son. These works are significant because they establish the historical fact that interest in rhetorical communication is nearly five thousand years old; the actual contribution they made to subsequent rhetorical theory was minimal. It is very doubtful that rhetorical theorists for several thousand years afterward were even aware that these works had been written.

The Greek Period

Most scholars agree that the history of rhetorical communication as we know it today begins some twenty-five hundred years after Kagemni’s early writing, during the fifth century B.C., at Syracuse, in Sicily. Although isolated bits of information concerning communication were found in Homer’s works, the formulation of the first works on rhetorical communication in Greece is generally attributed to Corax and Tisias. When a democratic regime was established in Syracuse after the overthrow of Thrasybulus, the citizens flooded the courts to recover property that had been confiscated during the reign of this tyrant. The “art of rhetoric” that Corax developed was intended to help ordinary people prove their claims in court. Although Corax and his pupil Tisias are usually credited with the authorship of a manual on public speaking, the work is no longer extant. We are not certain of its contents, but scholars have suggested that it included two items significant for the later development of rhetorical theory. The first was a theory of how arguments should be developed from probabilities, a theory that was to be much more fully developed by Aristotle a century later. Corax and Tisias are also generally credited with developing the first concept of organization of a message. They suggested that a message should have at least three parts: a proem, a narration or demonstration, and an epilogue. These three parts are roughly equivalent to the three parts we say should be included in a message today: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion.

Early writings indicate early interest in rhetorical communication.

The term sophistry is generally thought of today as referring to deceitful reasoning. As originally used, the term sophist referred to anyone who was a teacher. In Athens, during the fifth century B.C., a comparatively large number of itinerant teachers lectured on literature, science, philosophy, and, particularly, rhetoric. These sophists set up small schools and charged their students fees for tutoring. The schools proved to be so rewarding financially that a number of rather unscrupulous people were drawn into the profession. These were the individuals who eventually brought the sophists an unsavory reputation. It is most incorrect, however, to attribute to all the sophists the deplorable characteristics of these unscrupulous individuals. In fact, many of the sophists were highly moral people who made major contributions to the theory of rhetorical communication.

Protagoras of Abdara, sometimes called the father of debate, was one of the first and most important sophists. In his teaching he contended that there were two sides to every proposition and that speakers ought to be able to argue either side. This view, which is still commonly accepted by teachers of argumentation, debate, and law, was one of Protagoras’s three main contributions to rhetorical thought. Protagoras also introduced the concept of commonplaces, that is, segments of speeches constructed in such a way that they had no reference to any particular occasion but could be used whenever a person was called upon to speak in public. Protagoras is also generally credited with being the founder of our system of grammar. He classified and distinguished the parts of speech, the tenses, and the moods.

Contemporary with Protagoras was Gorgias of Leontini. Gorgias is recognized as one of the first rhetoricians to perceive the importance of exciting the emotions in persuasion. The Platonic dialogue that bears Gorgias’ name portrays him as an individual not concerned with the ethics of his means of persuasion. In addition, Gorgias placed great emphasis on style, particularly on the figures of speech, such as antithesis and parallelism. Later rhetoricians who concentrated on the cultivation of a highly literary style of address may be thought of as following the tradition started by Gorgias.

The most influential of the Greek sophists was clearly Isocrates. Indeed, his influence probably was even greater during the Greek period than that of Aristotle. Isocrates also represents the best of the sophists in another context: He was a highly ethical man with noble ideas and unimpeachable standards of intellectual integrity. Just where he received his education is not clear, but it is believed that he studied under Tisias and that he also may have studied under Gorgias and Socrates. There is no question, however, about his impact as a teacher. When he set up a school of oratory, he soon had more students than any other sophist, even though he charged unusually high tuition fees. In fact, he managed to acquire considerable wealth as a result of his teaching.

A reticent man with a weak voice, Isocrates was never himself an orator. However, he wrote many fine orations for other people to deliver. Although many discourses by Isocrates are extant, his An of Rhetoric has been lost. Two of his works, Antidosis and Against the Sophists, provide us with some insight into his thinking.

Isocrates made two major contributions to the theory of rhetoric. One was his development of rhetorical style. He took the artificial and exaggerated style of Gorgias and refined it into an appropriate vehicle for both spoken and written communication. Probably Isocrates’ most important contribution was his view of the proper education of the ideal orator. He believed that the whole person must be brought to bear upon the process of communication. Therefore, the orator should be trained in the liberal arts and, above all else, be a good person. This view had a major influence upon both Cicero and Quintilian.

Although we refer to the teachers of rhetoric during the early Greek period as the sophists, we should take care to avoid thinking of the individual sophists as being all alike. They were as diverse as teachers are today. Although some were exhibitionists and unscrupulous practitioners, others were highly moral and significant theorists. From this group sprang both ideas that were to become basic tenets of solid rhetorical theory and ideas that were to lead to the decay, and almost the demise, of rhetorical theory. The sophists’ contributions to their society were major, and their contributions to our society’s view of communication are only slightly smaller.

Plato is generally credited with two major contributions to the development of rhetorical theory. Clearly one of his most important contributions, which he presented in his dialogue the Gorgias, was his stinging criticism of the rhetoric practiced in his day. He likened it to cookery and cosmetics and suggested that it was merely a form of flattery. It is important to emphasize that this was the sophists’ rhetoric of excess, not the kind of rhetoric that developed after Plato. Plato’s more important contribution was the foundation for an art of rhetoric laid down in the Phaedrus, which involved the composition of three speeches on love. There he gave his thoughts on what would be necessary in order to establish a truly good theory of rhetoric. Plato is sometimes credited with a third contribution: that he served as a catalytic agent for his pupil Aristotle. Some people consider Aristotle’s Rhetoric as an answer to the criticism of rhetoric made by his teacher. It is not known whether this is true but the Rhetoric clearly does provide answers applicable to Plato’s criticism, and his views certainly cannot be considered extensions of Plato’s.

Most rhetorical scholars agree that Aristotle was the greatest theorist ever to write on rhetorical communication, and his Rhetoric is the most influential work ever composed on the subject. The Rhetoric, which he wrote about 330 B.C., consists of three books. They have been called the books of the speaker, of the audience, and of the speech.

Book I discusses the distinction between rhetorical communication and dialectical communication (the process of inquiry). Aristotle takes his contemporaries to task for dwelling upon irrelevant matters in their rhetorical theory rather than concentrating on proofs, particularly enthymemes (arguments from probabilities). Rhetoric is defined in this book as “the faculty of discovering in a particular case what are the available means of persuasion.” This faculty, Aristotle suggests, is the distinguishing element of rhetoric and belongs to no other art. To Aristotle, the means of persuasion are primarily ethos (the nature of the source), pathos (the emotion of the audience), and logos (the nature of the message presented by the source to the audience). In Book I, the author dwells upon the nature of rhetorical thought and particularly upon the concept of invention. His main guide to the invention of argument for persuasion is the use of topoi, or “lines of argument.” Aristotle also distinguishes three different kinds of speaking: deliberative (speaking in the legislature), forensic (speaking in the law court), and epideictic (speaking in a ceremonial situation). Given the nature of the culture of Greece during his time, ...

Table of contents

Citation styles for An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication

APA 6 Citation

Mccroskey, J. (2015). An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication (9th ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1561222/an-introduction-to-rhetorical-communication-pdf (Original work published 2015)

Chicago Citation

Mccroskey, James. (2015) 2015. An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication. 9th ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1561222/an-introduction-to-rhetorical-communication-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Mccroskey, J. (2015) An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication. 9th edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1561222/an-introduction-to-rhetorical-communication-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Mccroskey, James. An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication. 9th ed. Taylor and Francis, 2015. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.