![]()

Part I

Historical and conceptual contexts

![]()

1

Language learning and technology

Past, present and future

Deborah Healey

This chapter serves as the introduction to the handbook, touching on many of the issues that will be addressed in more depth in the rest of the book. The first section addresses what the field has been called – CAI, CALL, ICT, MALL, and more – and why a name is important. The next section looks at the varying roles of the teacher, learner, and technology in different parts of the world and over time. Few teachers now fear losing their jobs to a computer, but they may fear losing their jobs to those who know more about technology than they do. As learners are better able to access learning resources via technology, their role and that of the teacher will continue to change. The Internet has been a large force for change in language learning over time. The introduction of the Web created opportunities for a sea change in resource availability, especially with languages not spoken locally. With mobile devices, computing has become ubiquitous; the social web has emerged and become part of most people’s lives. These two factors are creating another revolution in ways that people communicate with each other, and thus how we can learn languages. Finally, this chapter will take current trend lines and make some guesses as to what may come, given where we’ve been and where we are going now.

What’s in a name?

Names are important. A name not only describes a concept, it also shapes how we interpret the concept. The early names associated with language learning with technology, such as computer-aided instruction (CAI), show both an emphasis on the machine and a behaviouristic approach to learners. The machine taught and learners sat and pressed keys in response. The mainframe-based PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automated Teaching Operations) system was created in the 1960s at the University of Illinois and became more widespread by the 1970s. The very acronym – ‘Programmed Logic’ – indicates the underlying mindset. Learners worked through increasingly difficult activities, and their ability to complete an activity (and its multiple-choice test) would either allow them to move on or send them to review material. Faculty members worked on remote terminals to create content, often collaboratively. Initial language teaching programs were basic drills, but PLATO became much more robust over time. Later implementations included audio and limited graphics. While the lessons were ‘programmed’, PLATO courseware came with curriculum.

Microcomputers: Technology for the masses

The advent of microcomputers in the 1980s made it possible for more computer use in the classroom. Much was still CAI-like drill and practice and was sometimes called computer-assisted language instruction (CALI). However, some early teachers using computers suggested a change of nomenclature to aim at language learning specifically. Davies and Higgins (1982), among others, suggested the term ‘CALL’: computer-assisted or computer-aided language learning, and it became the preferred acronym.

Publishers in the US focused attention on recreating some of the early drills typical of PLATO systems. Some were sequenced so that they contained a curriculum. Many others were simple drills with a menu of possibilities. Where teachers took an active role in helping learners select material, more learning could take place. Language teachers also created simple drill-and-practice programs in BASIC, though rarely at the level and complexity of what was done with PLATO.

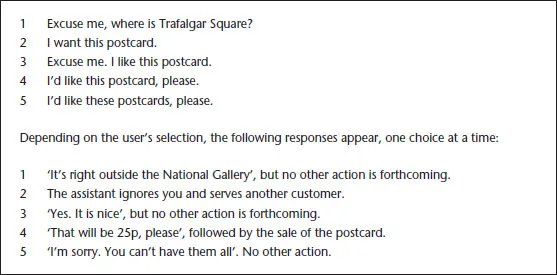

Outside the US, the British Council was actively producing software for language learning. There were some drills, but many programs were simulations, such as London Adventure or Lemonade Stand. Students playing London Adventure were told to purchase a set of items in London. They had to make the appropriate choices about how to interact with shopkeepers and others as they went from place to place. An inappropriate choice of language in interacting with a shopkeeper would result in the learners being unable to get what he or she was trying to find out or purchase. For example, Figure 1.1 shows an interaction from London Adventure.

These programs represented a focus on learning, not drilling. They also required teachers to take an active role in setting up groups and perhaps keeping score. The teacher and the learner were in charge, not the machine.

Figure 1.1 Interaction from London Adventure

Growth in terminology

As more computer programs became available, writers and researchers suggested different acronyms: Computer-enhanced language learning (CELL), computer-assisted writing (CAW) for writing programs, computer applications in second language acquisition (CASLA), and technology-assisted or technology-enhanced language learning (TALL or TELL). The Computer-Assisted Language Instruction Consortium (CALICO) retained the computer-assisted language instruction (CALI) acronym. CALI is still used, but more often in non-English languages than for English language instruction. As practitioners and researchers looked for ‘intelligent’ CALL, the ICALL acronym appeared and is still used for a subset of CALL. Although different names were discussed, CALL remained the most widely used term. It became part of CALL Digest and the CALL Interest Section of TESOL in 1985; the publication ReCALL in 1989; CALL Journal in 1990; EuroCALL in 1993; and many others.

Early Internet

In the 1980s, the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) expanded from its exclusive consortium with the US Department of Defense and selected research universities, becoming the Internet. Initially, the Internet was difficult for teachers to use and lacked content. It was a time of text-based MUDs (Multi-User Dungeons, based on Adventure and Dungeons & Dragons) that shifted over time into MOOs (Multi-User, Object-Oriented) and Internet Relay Chat (IRC) rooms.

These text-based environments allowed learners to interact with others who were in the same virtual space (‘rooms’ or ‘buildings’ in a MOO, or the chat space in IRC). Some teachers used the MOO space for interacting with other teachers. Diversity University (DU MOO), for example, offered scheduled meetings for teachers to talk with each other about selected topics. These interactions were like Chat, where participants overlapped each other and conversations became disjointed when more than a handful of people participated. Still, this was now ICT: information and communications technology. That term became widely used not only in language teaching, but also across education. It is the term used in the UNESCO ICT Standards for Teachers (2008; see also Kessler, Chapter 4 this volume), which addresses education as a whole. One of the best-known current users of the term in language circles is the website ICT4LT: Information and Communications Technology for Language Teachers (Davies 2012).

A related term that arose early on was computer-mediated communication (CMC). CMC was considered a subset of CALL, with its emphasis on learners communicating with each other using the Internet. The Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication began publication in 1995 – evidence of interest by educators and academics. With work by Tim Berners-Lee and the development of the web browser Mosaic in 1992–93, the Internet became the World Wide Web, and CMC became more feasible and common. Interest in research on CMC in discourse analysis continues today, often examining the communication taking place in social media. A related area of research on CMC focuses on digital literacies: how people communicate effectively using digital media. Because of concerns that CMC did not cover the full extent of what learners do with computers, CALL retained its popularity as the overarching term, especially in English language teaching.

More than just computers

The 21st century added Web 2.0 and new devices for language teachers and learners to use. As a result, discussions are ongoing about the most appropriate term to use to describe the new reality of learner/teacher-generated content, web-enabled devices, and mobile technology. The term TELL (technology-enhanced language learning) has reemerged. Terms with some reference to ‘mobile’ have also become more common, with mobile-assisted language learning (MALL; see also Stockwell, Chapter 21 this volume) the most frequent ‘mobile’ term used in material indexed by Google.

The new terms reflect the idea that ‘computers’ are not necessarily what language learners and teachers are using. New methods incorporate the creative potential of the so-called social web and the mobility of small devices. Still, not every learner uses mobile technology, so terminology that fully describes the range of what language teachers and learners do is still in flux. TESOL’s Technology Standards Task Force retained the term CALL in its work, with the proviso that it referred to the full range of digital technology-enabled activities. The UK-based International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign Language (IATEFL), however, uses the term ‘learning technologies’ in its Learning Technologies Special Interest Group. Perhaps that will become the overall term of choice, despite its broader focus than just language learning. We do need terminology to address technology use as mobile devices of various kinds become more common among language learners than computers.

Technology, teacher and learner roles

Terminology has provided some insight into the roles of technology, the teacher, and the learner. CAI was computer-centred instruction. Computer-assisted language learning shifted focus to student learning rather than instruction. In exploring how teachers and learners use technology, it is important to keep in mind the different roles that each can play.

Role of technology

Work in the 1980s by British researcher and theoretician John Higgins provided a dichotomy between a ‘magister’ and a ‘pedagogue’ role for computers. As he put it:

For years people have been trying to turn the computer into a magister. They do this by making it carry the learning system know as Programmed Learning (PL)… . PL in fact does not need a computer or any other machinery; it can be used just as effectively in paper form, and computers which are used exclusively for PL are sometimes known disparagingly as page-turners. The real magister is the person who wrote the materials and imagined the kind of conversation he might have with an imaginary student.

Suppose, instead, that we try to make the machine into a pedagogue. Now we cannot write out the lessons in advance, because we do not know exactly how they will go, what the young master will demand. All we can do is supply the machine with a template to create certain kinds of activities, so that, when these are asked for, they are available. The computer becomes a task-setter, an opponent in a game, an environment, a conversational partner, a stooge or a tool.

(Higgins 1983: 4)

The move to microcomputers opened a ‘tool’ use of computers for teachers and learners. Word processing became an option in the classroom. There are important caveats related to the type of writing instruction, language proficiency of the learner, and role of the teacher. Still, research continues to show an overall positive impact of word processing on second language writing. Benefits include better attitude towards writing, longer writing, greater willingness to edit and an end result of better writing in many cases (see e.g. Phinney 1989; Li and Cumming 2001; Pennington 2004). Other tools, such as spell-checkers, dictionaries, spreadsheets and authoring programs were also brought into the language classroom.

Taxonomies: Roles of technology

Higgins’s dichotomy of magister and pedagogue was further refined by Jones and Fortescue into three roles for computers: ‘Knower of the Answer’, ‘Workhorse’ and ‘Stimulus’ (Jones and Fortescue 1987). Another early book, Something to Do on Tuesday (Taylor and Perez 1989), built on Jones and Fortescue’s taxonomy and used ‘Knower of the Right Answer’, ‘Workhorse’ and ‘Stimulus’ to describe roles of software programs for Apple IIe, Atari, Commodore 64 and MS-DOS computers.

Two current well-known taxonomies are from Warschauer (1996) and Bax (2003). The Warschauer model sets three stages: ‘behaviouristic’, ‘communicative’ and ‘integrative’. The first stage, behaviouristic CALL, focused on drill and practice programs like PLATO and 1980s software. Instrumental CALL was the second stage, described as a computer-as-tool era. The post-Internet era is the integrative stage, where technology is integrated into classroom practice and language learning, not separate from it. Elements of earlier stages are still found in current uses of CALL.

The Bax model takes a somewhat different approach, with ‘restricted’, ‘open’ and ‘integrated’ CALL. Early use of technology in language teaching was not necessarily behaviouristic, but it was more limited in what it could do, thus the ‘restricted’ label. With the Internet and a pedagogy that does not focus on technology so much as use it for a purpose, we are currently in the open stage. Fully integrated CALL will emerge and become ‘normalised’ where there is no more ‘CALL’, just use of technology as a routine part of teaching, much like textbooks. As Bax writes:

This concept is relevant to any kind of technological innovation and refers to the stage when the technology becomes invisible, embedded in everyday practice and hence ‘normalised’. To take some commonplace examples, a wristwatch, a pen, shoes, writing – these are all technologies which have become normalised to the extent that we hardly even recognise them as technologies.

(Bax 2003: 23)

Role of the teacher

Identifying multiple roles for technology, however, does not fully address the dynamic in the classroom. The teacher and learner also have important roles to play. With PLATO, teachers were the designers and creators of language teaching programs. Carol Chapelle comments on PLATO:

The PLATO project also contributed to the professional expertise in CALL. The courseware developed on that system, which supported audio (input to learners), graphics, and flexible response analysis, was the product of language teachers’ best judgement of what supplemental course materials should consist of the in the late 1970s.

(Chapelle 2001: 6)

The teacher was behind the scenes, and the computer was a tutor. Students were recipients, especially when the lessons were offered in a fixed sequence rather than allowing learners to choose what they would work on. Technology was viewed as a way to free the teacher to do more interesting things in class by shifting drills from classroom time to computer lab time.

Taking a look through CALL history, the shift of technology from mainframe PLATO systems to microcomputer systems in the 1980s opened up computer use in teaching to far more people. In the UK, the low-cost BBC Micro and Sinclair Spectrum enabled teachers to begin creating their own material using BASIC. The limitation was the very small screen and chiclet-like keyboard. In the US, Commodore’s Vic-20 and C-64 models were lower-cost options than the Apple IIe. Teachers could create their own material using BASIC on any of those computers, but commercial publishers moved to the Apple IIe platform for early CALL material. It is important to note in this Internet-centred age that programs were platform-dependent; what ran on a BBC Micro had to be rewritten to be use...