eBook - ePub

The Japanese Police System Today: A Comparative Study

A Comparative Study

- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

What role do their respective police systems play in the very different crime rates of Japan and the United States? This study draws on direct observation of Japanese police practices combined with interviews of police officials, criminal justice practitioners, legal scholars, and private citizens. It compares many Japanese police practices side by side with U.S. police practices, and places the role of the police in the broader cultural and historical Japanese framework.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Japanese Police System Today: A Comparative Study by L. Craig-Parker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Overview: Crime in Japan and the United States

In the United States awareness of Japan has increased rapidly in recent decades, largely due to what was perceived as a growing economic threat. With economic anxiety, however, came a certain amount of cross-cultural curiosity. Among the points of interest is Japan’s surprisingly low crime rate. Though less dazzling than the economic achievements of “Japan Inc.,” facts such as this low level of crime have continued to draw our attention to a national phenomenon that is far more complex and, I feel, far more interesting than the simple ability to produce good, small cars. Although Japan was mired in a deep recession in the 1990s, with bankruptcies and suicides being linked to the economic despair, it was not long ago that Americans were apprehensive that the Japanese were out to buy up some of the most prestigious properties—including Rockefeller Center in New York City—in the United States. Michael Crichton’s best-selling novel Rising Sun (1992), in which powerful Japanese business interests attempt to thwart a murder investigation in Los Angeles, only added fuel to the fire.

During my first visit to Japan in 1980–81, I strolled the streets of Tokyo, Kyoto, Yokohama, Kobe, Sapporo, and a number of other Japanese cities and towns without once feeling threatened or menaced by an individual or a group. I rode subways that were not defaced with graffiti, and I wandered through parks at midnight in the heart of Tokyo without apprehension. I concede that this state of mind took a while to acquire, since I had become accustomed to the streets of New York and Boston long before arriving in Tokyo. Though not altogether crime free, by any yardstick one wishes to use, Japan continues to provide a relatively tranquil and safe social environment. This remarkable feature of Japanese society deserves attention from the United States, which is in the midst of a crime crisis. One way to illustrate the success of the Japanese in this area is by comparison with the United States, and while this work is not intended to be systematic, point-by-point comparison of each country’s approach to law enforcement, I would like to begin with a comparative perspective. The primary purpose of this book, however, is to explore the role of the police in community relations in Japan, as seen through the eyes of a psychologist.

It is difficult to draw comparisons between crime data reports from Japan and the United States because the different levels of public confidence in police effectiveness in these countries result in different rates of reporting crime. In addition, descriptive terms for crimes—even after making allowances for possible inaccuracy of translation—may have different connotations in each country, further confounding comparisons.

It appears that the Japanese report a larger percentage of crime than Americans do. This is evidenced by the discrepancies between their various crime indices and our own. Because of the unreliability of statistical data issued in the Uniform Crime Reports of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the U.S. Department of Justice began direct household surveys of crime a number of years ago. This approach revealed, not surprisingly, a significantly higher incidence of actual crime than that reported by citizens to police.

The FBI, as the clearinghouse or coordinating agency, must contend not only with the outright manipulation of data as reported by many police departments, but also with their varying systems of crime classification. Admittedly, there have been attempts to standardize police reporting of crime, but these appear to have enjoyed only modest success. Pressure to report certain types of crime has political implications for local police chiefs. A police analyst eager to obtain federal funds for a pet project may “stack the deck” in a certain category. Thus, ultimately, the FBI must rely on the veracity of the reports issued by the hundreds of police agencies throughout the nation, even though error and bias are known to exist.

The National Police Agency in Japan coordinates policy-making and standards for the forty-seven prefectural police organizations throughout the country and thus has an advantage when it comes to the standardization of police practices and the compilation of data. The reporting system and classification of crime data are therefore more accurate. Because high-ranking police officials are insulated from the whims of local politicians, and because they are rotated in their assignments approximately every two years, they are not likely to be vulnerable to pressures to tamper with the raw data in their possession. This subject will be discussed later in detail.

Notwithstanding the problems inherent in reporting and compiling statistical data, what do some of the comparisons between Japan and the United States indicate for a recent year? Although the Japanese population was 126 million in 1996 and the United States population was 265 million (a bit more than double), the incidence of crime was much greater in the United States (U.S. Department of Justice 1997; National Police Agency of Japan 1998). For example, the total number of homicides in Japan was 1,257 in 1996 compared to 19,650 in the United States. In the case of robbery, there were 535,590 reported to the police in the United States compared to just 2,463 robberies reported to the police in Japan. The numbers for rape were also dramatically different—in the United States 96,250 rapes were reported, while in Japan the comparable number was just 1,483. The usual caveat applies here, that although law enforcement authorities in both countries have used various means to encourage the reporting of the crime of rape, it continues to be underreported in both nations. An inspection of the category larceny-theft (including auto theft) shows that in the United States there were 9,298,900, while in Japan during 1996 there were 1,588,698 offenses reported to the police (U.S. Department of Justice 1997; National Police Agency of Japan 1998). Thus, there are staggering differences in the numbers of crimes committed in both countries, with the number of robberies representing a particularly dramatic difference—approximately 220 times as many robberies in the United States as in Japan. Interestingly, this is a roughly similar ratio to the one reported in the 1984 edition of this book.

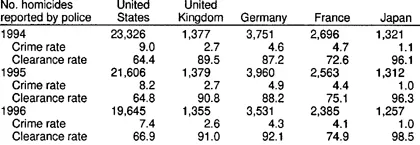

Table 1.1 provides comparisons with four other nations on homicides, homicide clearance rates, and homicide rates per 100,000 population as reported by the Japanese Ministry of Justice (1998). The data are consistent with the above-mentioned crime statistics in revealing not only the large discrepancies between homicide rates in the United States and the other developed countries, but in clearance rates as well. Here Japan is superior not only to the United States, but also to the other Western European countries. All five countries showed modest declines in actual numbers of homicides between 1994 and 1996. In the comparison on rate of homicide between the United States and Japan, the rates of 1.0 for Japan and 7.4 for the United States for 1996 reveal a slight improvement in the U.S. rate that the author reported back in 1980. Then the numbers were 1.6 Japan and 9.0 United States. European countries do not have the glaringly high crime rates of the United States, but even in comparison with them, Japan still has impressively low crime rates. How can this be accounted for, considering that Japan’s population is as urbanized, industrialized, and sophisticated as those of the most advanced Western nations? This is not an elusive matter that defies understanding. Moreover, by understanding it, we can gain a greater appreciation of our own crime problems.

Table 1.1

International Comparison of Homicides, Homicide Rates, and Homicides Cleared (rates are per 100,000 population)

International Comparison of Homicides, Homicide Rates, and Homicides Cleared (rates are per 100,000 population)

For years, the Japanese seemed to accept without question the difference between their society and others’ on the subject of crime control. Over the years, however, the publication of various books by David Bayley, Walter Ames, and William Clifford has helped to awaken Westerners to what is occurring in the Japanese system of justice, and in turn the Japanese have become more conscious of their own success. Alvin Toffler, the author of Future Shock, collaborated with his wife, Heidi, on a series of articles that focused on the strengths and weaknesses of Japanese society. The Tofflers expressed concern that the media bombardment of the early eighties, which emphasized Japanese successes, would result in a “backlash.” In their view, a caricature had been emerging in which “we see 115,000,000 docile, dedicated and highly motivated workers smoothly managed by a few giant, paternalistic corporations whose top leaders work hand-in-glove with an understanding government” (Toffler and Toffler 1981). In their opinion, that picture was far from the truth. The notion of Japan As Number One, the title of Ezra Vogel’s 1980 book, grossly oversimplified a nation that had real weaknesses and vulnerabilities in addition to its highly advertised strengths. As one example, they cite Japan’s energy problems. While in the United States we rely upon other nations for just 22.4 percent of our energy requirements, Japan must import 86.3 percent of its energy. Concerning food supplies, the Tofflers reminded us that while Americans were among the top food exporters in the world, the European Economic Community must import 25 percent of its food and the Japanese are required to import over 50 percent of their food to meet demand. In short, while Japanese fuel-efficient automobiles, technologically sophisticated radios and television sets, and other quality products attracted wide attention, there was a vulnerability acknowledged by few at the time. The so-called economic miracle or the “bubble economy” of the early 1990s burst in a major recession, with extensive bankruptcies and a major decline in real estate values. Thus, the Tofflers’ assessment proved prophetic.

The issues related to the low crime rate in Japan that will be explored in this book include the following: first, the homogeneous makeup of Japanese society, which is a powerful factor in exerting social controls on illegal, and in many instances, deviant behavior. There are very few minorities in Japan, with Koreans representing the largest group, but they number only approximately 700,000 in a total population of 126 million. However, by the late 1990s, increasing numbers of foreigners, particularly Chinese, were causing concern for Japanese justice officials. A chapter on this subject addresses this problem of the “internationalization of crime.”

A second issue, which is not easily separated from the overall social fabric of Japanese life, is the large network of both formal and informal groups. Membership in a group or one’s role in the group appears to be far more important than individuality, which is so highly prized in the United States. The emphasis on teamwork and the support Japanese offer one another clearly has implications for the low crime rate. Japanese family relationships are important in any discussion of the role of the group. Family members have a sense of responsibility for one another. The nature of this responsibility and the part played by family and larger community groups will be examined at length.

As a corollary to the closeness that develops through group life, the Japanese attempt to solve interpersonal conflict and seek harmony wherever possible. Japanese are fond of attributing their ability to get along with one another at least in part to the fact that they are living in a small island country. As I noted in an article for the Japan Times: “Japanese rarely act on feelings of hostility in public. A shove will not bring retaliation in a physical way, or probably even a verbal way. In Chicago, an obscene gesture could possibly result in your summary execution by the offended party. A shove in a New York subway might conceivably result in a knife between your ribs” (Parker 1981).

The Japanese also help to discipline one another through informal assistance and intervention. While occasionally police have to assist drunks, fellow workers are far more likely to come to their assistance. In contrast, Americans tend not to associate in groups as often, and a drunk is more likely to have to rely on public officials for help than on a colleague or friend.

Related to these other social values is the powerful role of conformity. Despite the westernization that has taken place in Japan since World War II, the pressure to conform is still very strong. The Japanese have a saying: “The nail that sticks up will get hammered down.” American Fulbright lecturers, often unacquainted with Japanese society, express dismay that their students demonstrate little willingness to speak out and engage in energetic debate in class sessions. The Japanese student is afraid to stand out from the rest of his or her classmates. It is not unusual to hear of Japanese businessmen who have worked abroad for a number of years struggling to find their place in their companies upon returning to Japan. They may lose out on their promotions or advance at a different rate from their colleagues because they are suspected of having been tainted by their exposure to foreign ways. Similarly, students who receive their college education in the United States or other Western nations are sometimes handicapped when they have to compete with their Japanese-educated fellows for jobs. This sort of conformity, as will be seen, carries over into the realms of crime and crime prevention.

The legal system reflects the value of conflict resolution through nonadversarial methods. There is considerably less litigation in Japan than in other industrialized nations. The first response to coping with a neighborhood problem is not to consult one’s lawyer for advice, but to attempt to work out a compromise with one’s potential adversary. There are only 3 percent as many lawyers in Japan as in the United States—a figure that reflects this lesser demand for litigation.

The Japanese generally have much greater respect for legal and governmental institutions than do Americans, and the police benefit from this attitude. Unlike the situation in the United States, where police, particularly in larger cities, are beleaguered and viewed with suspicion, Japanese police are generally trusted and respected. The development of the legal system and the historical evolution of police services will be discussed later in this book.

In outlining some of the reasons for the low crime rate in Japan, one cannot ignore the strict gun control laws. In 1996, just 128 crimes were committed with guns. Strict regulations contribute to a low incidence of firearms-related crimes in Japan, and in 1996 there were just forty-three firearms-related murders and attempted murders (National Police Agency of Japan 1998). Below is the policy concerning firearms and swords in Japan:

In Japan, in principle, possession of firearms and swords is prohibited under the Firearms and Swords Control Law. The Law’s intent is to prevent danger and to secure the public safety.To possess firearms, one must obtain a license from the Prefectural Public Safety Commission. No firearms license is granted to persons under age 18 (or under 20 for a hunting gun), persons suffering from mental disorder, persons addicted to drugs, persons with no fixed residence, persons having a criminal record (particularly in violation of the Firearms and Swords Control Law), and persons, like Boryokudan members, who are justifiably feared as a threat to public safety.Gun licenses must be renewed every three years. As of 1996, approximately 440,000 hunting guns and air guns were licensed.Handgun regulations are the most restrictive. Handgun possession is almost totally banned, except for legally permitted police officers and Self-Defense Forces personnel only while on duty, and a limited number of sport pistol shooters permitted by the prefectural Public Safety Commission.Possession of a toy gun is also prohibited as long as the gun falls under the category of “imitation gun.” Whether a toy gun is regarded as an “imitation gun” depends on its resemblance to a genuine one in appearance, mechanism, or function. (p. 35)

This policy is clearly one of the major reasons for the low rate of violent crime in Japan, and Americans could take a lesson from the Japanese in this respect. My Japanese colleagues indicated that they could not understand the obsession many Americans have with gun ownership.

Economic considerations are also important in accounting for Japan’s comparatively low crime rate, notwithstanding the recession of the late 1990s. Examining averages in Japan and the United States for income, production, and other economic factors is misleading because although the figures often parallel each other in a general way, they do not disclose important underlying variations. Particularly important in the case of Japan is the generally high standard of living and the broad distribution of wealth among all social strata. Unemployment, although higher in the 1990s, is still lower than in the United States. For 1997, the unemployment rate in Japan was just 3.4 percent, while in the United States it was 4.9 percent (Foreign Press Center 1999). Most Japanese consider themselves members of the middle class. Still, the postwar Japanese policies such as lifetime employment and seniority-based salaries have changed dramatically as the economic recession has taken its toll. Gradually firms are beginning to lay off employees in economically dist...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Preface

- 1. Overview: Crime in Japan and the United States

- 2. The Historical and Legal Framework

- 3. Overview of Police

- 4. Kōban Police

- 5. Attitudes of the Police toward Their Work

- 6. The Hokkaido and Okayama Prefectural Police Forces

- 7. The Investigation of Crime

- 8. Courts, Corrections, and Probation

- 9. Crime by Foreigners

- 10. Crisis with Youth

- 11. The Police and the Community

- 12. Conclusion

- References

- Index