![]()

Is there anything more intriguing and important than discovering how children come to be as they are and how we can support them as they develop so many skills and understandings? This is a complex undertaking due to the individual nature of children. Many are lively, full of excitement and promise, highly motivated to learn and confident with expectations and resolutions of their own while others are timid, distressed and reluctant to join in activities and learn new things and there are all shades in between. But understanding them all is particularly important for this is their fastest learning time. As long ago as 1977, Professor Colwyn Trevarthen made a number of claims that help practitioners justify the importance of the work they do. This is important as it is sometimes difficult to summarise such a complex endeavour. He wrote:

• The brain of every child in every culture goes through the same developmental stages.

• Children learn 50 per cent of everything they know in the first five years.

• Children are intrinsically motivated to learn.

• Curiosity is needed to develop the brain.

• Children need the right experiences at the right time.

The first claim eases observation in a multi cultural setting, explaining as it does that development follows the same pattern in all children. Yet practitioners have still to discover what stage each child is at and how they prefer to learn. They realise that although the stages are the same, not all children will reach the same level of achievement and the rate of progress will be different. The second claim is huge but doesn’t hold surprises for those experienced in interacting with young children. They are constantly delighted by the ways children expand their understandings and visibly grow in stature before their eyes. Few children lack curiosity but planning the best experiences to encourage their abilities and skills can be challenging. Listening to the children and finding their preferred ways of tackling problems could be useful ploys i.e. by cueing in to their interests and really listening to what they have to say. Given that they are primed to learn, it can be a rewarding experience to find that most children can not only respond to the learning experiences they encounter, but make choices and find innovative and creative responses.

Some children appear to have every advantage. Even being big for their age has certain benefits. While at first sight this may seem strange and presumptuous, Bee and Boyd (2005) claim that stature makes a big difference to children being popular and competent. This is because other children tend to look up to those who are ‘big’ and this is often reinforced by adults giving them more challenges and greater responsibility. And when expectations are higher, the children raise their game. Little children tend to be more sheltered with adults often doing things they could manage themselves! There is an important message for adults here.

If children come from advantaged backgrounds they will be likely to have more physical resources in terms of books and more opportunities to experience cultural events. However these things may come at the cost of having less quality time with parents or freedom to play so the different potentials need to be carefully considered by families in the knowledge of their child. Unfortunately, many children from less well-to-do homes do not begin their education on a level playing field. In some families ‘other concerns’, perhaps financial, perhaps health issues detract from the attention that can be given to the children. These differences have to be understood when studying the impact of the nurture/environmental side of development. Many practitioners give time and resources to compensate for any lack. Some children from advantaged and some from disadvantaged backgrounds will be gifted and talented, the latter group probably overcoming hurdles to shine, but many do!

Yet another group of children have special needs or in the newer term learning differences and these impact on learning if memorising or organising (intellectual difficulties) or movement/social/emotional difficulties restrict what children can do. A smaller but sadly increasing number have profound disabilities such as autistic spectrum disorders that hinder their ability to participate in many activities. (The ratios for autism have moved from 1:1000–1:100 children (Moore 2012)). A great deal of preparation needs to happen to enable these children to make the most of their time in school.

Even children in the same family can be ‘chalk and cheese’ with one child athletic and extrovert, another musical and shy and a third aggressive and moody. These differences must suggest nature or inherited differences rather than nurture or environmental ones since the upbringing has been largely the same. However Carter (2000) explains that even with twins, minute differences in the womb can cause differences. Whatever the reason, the differences indicate that each child requires a different level and kind of support. Parents and practitioners wonder, ‘Why should this be?’ ‘How can I best communicate with each of these very different children?’ ‘How will I discover what each child’s needs are?’ and ‘How can I plan the most stimulating learning opportunities to enhance each child’s profile?’ Finding answers is the constant concern of all the adults that interact with the children as they recognise the responsibility they have in nurturing them in this, the fastest learning time. For this is the time when the brain is most ready to learn. In the early years, the children’s brains are ‘plastic’ i.e. most responsive in terms of absorbing and adapting to different kinds of input. Young brains are intrinsically curious to learn, primed to make the new and vital connections between neurons (brain cells) that allow new skills and creative abilities to develop. Early years education at home and at nursery or children and families’ centres aims to nurture these early potentials, hopefully through providing a curriculum based on play. At the same time a process called maturation ensures that basic skills such as walking and speaking develop too. Maturational skills are intrinsic to development. In children without difficulties they do not need to be taught.

When children come to early years settings for the first time, practitioners focus on welcoming both them and their families so that the beginning of a social bond is formed. Then, over time they observe and assess how each child matches all the milestones of the different aspects of development. But as children are such individual young people, making sense of what they choose to do and recognising the progress therein is a daunting task. This is especially so as development is not a smooth path – it comes in stops and starts, but although children find they are more competent in some areas than others, there is a sense that the different aspects of development blossom together. (See Table 1.1 and Appendices 1 and 2 for more information on developmental milestones.)

■ TABLE 1.1 Developmental progress in three key areas | Play | Language | Movement |

5 years

Can initiate or join in role play. |

Can follow a story without pictures. Can read simple words. |

Can run and jump, ride a bike and zip a coat. Understands the rules of major games. |

4 years

Understands pretence and develops fears of the unknown. Develops imaginative games, not always able to explain rules. |

Knows colours and numbers. Can explain events, hopes and disappointments. Able to listen and focus. |

Can climb and swing on large apparatus. Has a developed sense of safety outdoors. Can swim. Enjoys bunny jumps and balancing activities. |

3 years

Enjoys group activities e.g. baking a cake for someone’s birthday. Understands turn taking. |

Uses complex sentences. Understands directional words and simple comparisons e.g. big/ small. |

Can ride a trike and climb stairs. Climbs in and out of cars/buses independently. Can catch a large ball. |

2.5 years

Develops altruism especially for family members. Understands emotional words e.g. happy, sad. |

Uses pronouns and past tenses adding ‘ed’ to form own version of past tense. |

Uses a step-together pattern to climb stairs. Can walk some distance. |

2 years

Beginning to play alongside a friend for a short time (parallel play). |

Rebels – says ‘No’. Can form two word sentences but comprehension is far ahead of speech. |

Can walk well but jumping is still difficult. Climbs on furniture (crawling pattern). |

18 months

Sensorimotor play exploring the properties of objects (solitary play). |

Has 10 naming words. Points to make wishes known. |

Can crawl at speed and walk but jumping is not developed. Balance is precarious! |

1 year

Walks unsteadily, arms and step pattern wide to help balance. |

Enjoys games e.g. peek-a-boo. Beginning to enjoy books and stories. Monosyllabic babbling. |

Plays with toys giving them correct usage – simple pretend e.g. feeding doll. |

6–8 months

Can sit unsupported briefly. Rolls over. Attempts to crawl. |

Makes sounds and blows bubbles. |

Reaching out for objects now. Changing objects from one hand to the other. |

0–4 months

May be able to support head but weight of head makes this difficult. Strength developing head to toe and centre to periphery. Can lift head briefly in front lying. |

Early communication: responds to voices: can make needs known. |

Plays with hands as first toy. Can hold object placed in hand but cannot let go – object drops. |

But of course it is one thing having charts, another to be able to ‘see’ what is going on. This takes experience, a clear idea of what is to be observed, a record of developmental changes and an intervention plan when challenges need to be extended or when there are developmental blips.

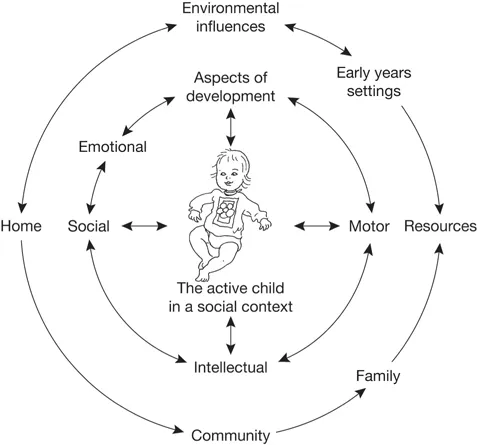

Since accurate observation and assessment is so challenging, having a structure to aid the process can be achieved by studying the four aspects of development separately, always remembering two things. The first is that other factors such as heredity and maturation (genetic influences) and cultural mores and resources (environmental influences) play a significant part in the process of development. The second is that although the four aspects are separated out to allow focus, they do constantly intertwine with progress in one affecting all of the others too. This can be shown in diagrammatic form (Figure 1.1).

■ FIGURE 1.1 Different aspects of development

The four aspects of development, i.e. motor, social, emotional and intellectual, prompt a number of age-related questions to guide observations. These are:

1. Motor or movement. Have the children reached their motor milestones? (See Appendix 1.) Do they appear to be strong or are they floppy? Can they crawl using the cross lateral pattern, walk without stumbling, handle early years equipment safely and even for a short spell, can they be still? Are they willing to venture onto apparatus such as a low bench and can they balance there? Do they demonstrate that they are strong enough to carry out the age-appropriate skills of daily living e.g. carrying plates of food at snack without spilling or getting their coats on without help? Is there any strange pattern when they walk? (A strange gait can be an early sign of difficulties and should be monitored closely to find if maturation ‘works’ or if further scrutiny is necessary. Walking on tiptoes often causes concern but u...