- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The mass protests that erupted in China during the spring of 1989 were not confined to Beijing and Shanghai. Cities and towns across the great breadth of China were engulfed by demonstrations, which differed regionally in content and tone: the complaints and protest actions in prosperous Fuijan Province on the south China coast were somewhat different from those in Manchuria or inland Xi'an or the country towns of Hunan. The variety of the reactions is a barometer of the political and economic climate in contemporary China. In this book, Western China specialists who were on the spot that spring describe and analyze the upsurges of protest that erupted around them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

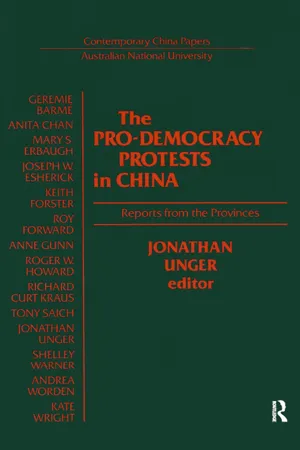

Yes, you can access The Pro-democracy Protests in China by J. Unger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE CAPITAL

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BEIJING PEOPLE’S MOVEMENT

The spontaneous demonstrations that filled Beijing’s streets for some seven weeks in 1989 were unprecedented in the history of the People’s Republic. They revealed a high level of frustration with the reform program initiated in the late 1970s and exposed deep divisions within the Party leadership about China’s future development. The decision to use force to crush the protests rather than to engage in dialogue highlighted how out of touch Deng Xiaoping and his supporters are with their own society. As a result, they face a difficult future without the positive support of key sections of the urban population.

This paper covers three aspects of the Beijing people’s movement. First, the problems with the urban reform program that provided a potential for unrest are examined. Secondly, the development of the movement in Beijing is covered. Finally, the response of the authorities is outlined.

Even though most attention in the paper will be paid to the students, the term ‘Beijing people’s movement’ is preferred to the narrower term ‘Beijing students’ movement’. This preference is based on the fact that although the movement was started and dominated throughout by the students, it expanded to gain the support, tacit or direct, of a significant portion of Beijing’s urban population. This was displayed most powerfully when the citizens of Beijing rallied to resist the martial law troops sent into the capital from 19 May onwards. The occupation of Tiananmen Square, the symbolic centre of Chinese communist politics, meant that the struggle in Beijing became one for control of the nation. I was in the capital during the crucial days of May and June; and this afforded me the opportunity not only to observe the movement but also to gather many of the materials used in this paper.1

Background to the Beijing People’s Movement

The protest movement has to be understood in the context of problems with the urban reform program that became increasingly apparent from the mid-1980s onwards. While white-and blue-collar workers were disturbed by the increase in inflation that was eroding their economic gains, intellectuals and students became frustrated with the postponement of thorough-going political reform. The frustration of these key groups with the reforms explains why the student-launched movement was able to spread its influence to other sectors of society and thus present the authorities with such a major challenge.

Since 1978, the leadership under Deng Xiaoping has tied its legitimacy more closely to its ability to deliver the economic goods than has any leadership since the founding of the People’s Republic. Urban workers were offered the vision of a more rationally functioning economy that would put more goods on the shelves and that would lead to a consistent rise in living standards. Key groups of technicians and intellectuals were allowed greater freedom in return for their input into the pursuit of economic growth. Since 1979, moreover, measures were introduced to improve both the prestige and material conditions of the intellectuals. As a group they were defined officially as a part of the working-class, a considerable improvement on their situation of the early 1970s when they had been denounced as the ‘stinking ninth category’. Their improved conditions and the greater freedom they were granted to engage in academic debate were tempered by the need to stay within the wider parameters set by the Party centre. However, as the Eighties progressed most intellectuals and students began to fall behind in terms of material conditions. This left greater intellectual freedom as the most tangible benefit of the reforms. Once this became threatened there remained little to support.

Problems arose with the system of regime patronage, moreover, when the leadership divided over fundamental issues and the guidelines were redefined in such a way that many of these ‘loyal intellectuals’ now fell too far outside of the realm of the acceptable. The forced resignation of General Secretary Hu Yaobang in January 1987 as a result of student demonstrations was a major turning-point for many of these intellectuals. Hu was seen by many as supporting further experimentation with political reform and as the most important patron of intellectuals within the top leadership. His dismissal was followed by the expulsion from the Party of three prominent intellectuals and a short-lived campaign against ‘bourgeois liberalization’. As a result, critical intellectuals began to question the validity of the tacit agreement. It seemed that the Party could not be relied upon to keep its part of the bargain. Many of the harsh judgments that had been reserved for private discussion were thrown into the public domain. The disillusionment with incomplete reform in the political sphere caused critical intellectuals to question the validity of working within the constraints laid down by Deng Xiaoping. They began to ask each other whether reform from above was feasible.2

One aspect of the reforms from which the intellectuals had benefitted was the policy of ‘opening up’ to the outside world. From the perspective of the regime, it could be said that this policy was too successful. Not only did China’s intellectuals pick up ideas from the West but also, more importantly, reformers formed strong links with critical intellectuals in Eastern Europe, especially Hungary. As a result, China’s intellectuals became more cosmopolitan in their outlook and more aware of alternatives to the policies offered by their own Party leaders. Reformist ideas from Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union were much more difficult for the Party leadership to reject out of hand than were Western notions of democracy and divisions of powers, which could be dismissed as ‘bourgeois’ in nature.3

Hu’s ‘resignation’ also came as a shock for the students. After all, their demonstrations had been used as the pretext to dismiss him. As an incipient elite, China’s students had been offered a place of prestige in China’s future in return for acquiescence to the Party’s overriding goals. But what the Party did not realize was that the students themselves wanted to play a major part in defining what that future would be. A sizeable number of them wanted China to move determinedly in the direction of reform; and it is noticeable that the two major rounds of student demonstrations – December 1986 and April-June 1989 – erupted after a perceived set-back for the reformers. In particular, these protest movements have to be seen in light of the unfulfilled promises for political reform that had been presented by Deng Xiaoping himself as an important part of the reform program.

The December 1986 demonstrations followed a summer of extra-ordinary debate in the official press on the need for a major shake-up of the political system. When China’s top leaders withdrew to their summer retreat of Beidaihe, it was expected that they would draft a document on political reform. Instead, the resolution published by the 6th Plenum of the 12th Central Committee in September 1986 stressed the need to improve work in the ideological and cultural spheres, issues identified with those who wish to limit the political reforms.

Thus, when the students took to the streets in December 1986, they did so with the intention of supporting a perceived Deng Xiaoping faction by giving renewed impetus to the need for greater political reform.4 Deng’s hard-line reaction to these demonstrations and the dismissal of Hu opened their eyes to the fact that Deng was no true friend. Their belief in the capacity of the Party to reform itself and significantly to revise regime practice was undermined. This opened the way for more radical actions subsequently.

To compound the problem, the urban working-class and state employees had lost faith in the economic reform program. Essentially, urban workers were being offered a deal that involved giving up their secure subsidy-supported low-wage lifestyle for a risky contract-based system that might entail higher wages at the possible price of rising costs and unemployment. Many urban workers decided to reserve their judgement. Their reservations were exacerbated by the leadership’s indecisiveness about urban reform that resulted in a stop-go pattern throughout the 1980s. The insecurity mounted when the reforms after 1986 resulted in spiralling inflation without consequent improvements in material living standards. Not surprisingly, talk of further price reforms in mid-1988 and reductions in subsidies created a sense of panic. Zhao Ziyang’s attempts, with Deng Xiaoping’s support, to produce rapid economic results created the inflation of 1988 and 1989 that threatened those on fixed incomes. Their declining living standards added to the reservoir of urban discontent.

To this extent the rise in tensions in the urban areas was a result of the failure of Zhao Ziyang’s economic reform program. Zhao had consistently applied macro-economic policy incorrectly. He appeared to be trying to expand the economy rapidly to win his own political legitimacy as a way of justifying further reforms. Instead he found himself politically sidelined by the end of 1988.

Urban anger was increased by the higher visibility of official corruption. Abuse of public positions and the privatization of public function had reached extreme proportions by the late 1980s. Chinese society had become one that was ‘on the take’ where, without a good set of connections and an entrance through the ‘back-door’, it was very difficult to partake of the benefits of economic reform. The sight of children of high-level officials joy-riding in imported cars was a moral affront to many ordinary citizens. It was not surprising that the student slogan of ‘down with official speculation’ found a large, enthusiastic audience.

By 1989, it was clear that in the eyes of many urban dwellers, the Party’s incompetence and moral laxness had eroded any vestigial notions that the Party constituted a moral force in Chinese society. Once the dams were breached by the students, a flood of supporters was waiting to defend the students and attack the authorities.

The Students Take to the Streets

Why, at that particular juncture, did the students take up the challenge? Secondly, how did they organize themselves, and finally, what kinds of issues did they raise?

As in 1986, the student demonstrations of 1989 have to be seen in terms of a preceding defeat for the reform program. The decisions taken at the National People’s Congress of March-April 1989 made it clear that the then General Secretary, Zhao Ziyang, and his pro-reform allies had lost the policy debate. Premier Li Peng and Vice Premier Yao Yilin not only reaffirmed the program of tight economic austerity but combined it with attempts to curtail political liberalization.5 The general malaise created by the reformers’ defeat needed only a spark to convert it into a major expression of discontent.

This spark, of course, was provided by the death of Hu Yaobang on 15 April. Whether true or not, the rumour that Hu’s heart attack had occurred while arguing the reformers’ case at a Politburo meeting gave impetus to the students’ desire to demonstrate. On the evening of 16 April some 300 students from Beijing University arrived at Tiananmen Square to lay wreaths in memory of Hu. The numbers began to swell as students from other colleges joined in. As with so many movements, a brush with authority gave the protests further impetus. On 20 April, when several thousand students gathered outside Zhongnanhai, China’s political nerve centre, to stage a sit-in and to demand that Premier Li Peng come out to talk with them, several were injured in a police charge. Official reports did not refer to student injuries but merely to troublemakers’ inciting the incident and wounding police agents. The episode supplied students with the weapon of martyrdom.

The students’ resolve was further strengthened by the tough editorial published in the People’s Daily on 26 April. The editorial condemned the students’ actions as a ‘planned conspiracy’ directed against the Party. The reaction was massive; Beijing witnessed its largest spontaneous demonstration since the founding of the People’s Republic. Despite official warnings that force would be employed to halt the protests, some 50–100,000 students broke through a series of police cordons to flood onto Tiananmen Square. Importantly, the demonstrations showed that there was a substantial reservoir of support for the students among the rest of Beijing’s population. Up to a million residents lined the students’ route, encouraging them on their way and providing them with food and drink.

Unlike the intellectuals, the students had not been integrated into the system of regime patronage. As with students in many countries, they were alienated from the younger people who were not students, as well as from the mainstream of the Party-dominated society. At the same time, although by no means well off, the students were not concerned so directly with the financial and social problems that beset the rest of Beijing’s populace. In addition, they were not subjected to the same stringent outside controls as the other sectors of the population and could take risks that other sectors of society could not afford. This created for them the time and space to think more critically about China’s future. Anyone who has spent time on Chinese college campuses in recent years must have been struck by the students’ increasing disregard for officialdom.

Many students expressed more iconoclastic ideas than the intellectuals, and it was clear that they were much more dubious than the latter group about the Party’s capacity to reform itself. In fact, on 14 May when well-known reformist intellectuals such as Yan Jiaqi and Dai Qing asked that the students evacuate the Square, effectively suggesting that the struggle now be left to Zhao and his supporters in the Party, they were denounced as ‘neo-authoritarians’.6 This friction between the students and such intellectuals persisted to the end. For example, on 2 June I spent most of the day on the Beijing University campus with Dai Qing. Her discussions were frequently punctuated by comments from students that she represented the ‘neo-authoritarian’ viewpoint because of her ‘capitulationist tendencies’.

The rapid spread of the protest movement was facilitated by the fact that most students lived on campus, with the effect that news could spread quickly among them. Secondly, the close proximity of many of the campuses in the Northwest district of Beijing made horizontal communications much easier. This guaranteed that speeches would be heard and strategically hung posters seen to maximum effect. The campuses soon became focal points for sympathizers from off campus.7

Student movements tend to be transitory, rising and falling quickly and unexpectedly. In part this can be accounted for by the relatively rapid turnover of student populations. What influences one generation does not necessarily affect the succeeding generation. However, China over the last ten years has been dominated by promises of political reform followed by the rejection of attempts to widen significantly the parameters of political debate. Thus, the formative adolescent years of successive cohorts of students have been dominated by the same themes. This has been compounded by the creation of a collective history of s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- Map

- Introduction

- Part I: The Capital

- Part II: Manchuria

- Part III: The Interior

- Part IV: The South China Coast

- Part V: The Yangtze Delta

- Index