- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Skyscrapers and High Rises

About this book

This work includes a brief history of skyscrapers as well as chapters on elevators and communications, facades and facing, mechanical and electrical systems, forces of nature, and much more.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Skyscrapers and High Rises by Shana Priwer,Cynthia Phillips in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER

1

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SKYSCRAPERS

In the history of invention, specific individuals often receive credit for the development of innovations that helped move society forward. Wilbur and Orville Wright, for example, made significant headway in the development of the airplane and are partly responsible for its initial burst of development. Benjamin Franklin relied on past inventions when he developed the bifocal lens, yet its ultimate invention is attributed to Franklin alone. Similarly, Alexander Graham Bell is known as the father of the modern telephone.

The path that led to the creation of the skyscraper was inherently different. No single genius is considered solely responsible for skyscrapers as we know them. The development of super-tall architecture was a collaborative venture that involved architects, engineers, mechanics, builders, masons, welders, and many other individuals.

The identity of the “first” skyscraper is the subject of much debate. Some of the first tall buildings were not skyscrapers in any modern sense of the word. Chicago was the site of some of the earliest attempts to build tall buildings after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. The seven-story Marshall Field Wholesale Store in Chicago, designed by Henry Hobson Richardson and built in 1885, was constructed of load-bearing masonry. Richardson's building, though not the tallest structure of the time, did point out limitations of the current technology and was therefore a key component in the development of the skyscraper.

The Home Insurance Company Building in Chicago, also built in 1885, was the first to use the new technology of steel-girder construction. Designed by American master architect William Le Baron Jenney, the building had one of the first load-bearing structural cage frames. It was much lighter than a comparable masonry building would have been. Stone masonry buildings were quite heavy and gave the appearance of a solid, structurally sound building. Steel is a physically lighter material, and because of the use of thinner structural members, the buildings using this new technology seemed less dense than their stone counterparts. Inspectors even worried about its stability and at one point called for a stop in construction. Other groundbreaking buildings followed, such as Chicago's Tacoma Building, built in 1887–1889, and the New York World Building, built in 1890.

The Marshall Field Wholesale Store Building, an early high-rise, was a predecessor to the skyscraper.

The individuals responsible for these masterpieces had many obstacles to overcome, and their collective solutions made possible the development of buildings that grew ever taller. Making skyscrapers habitable proved to be one of the most challenging problems in the entire design process. As developments in building materials and transportation progressed, taller buildings appeared in large cities across the United States, notably New York and Chicago. Innovations in steel and glass allowed for taller buildings, and the development of the Otis elevator allowed people to reach and occupy the upper levels of these structures. As technology and design rose to new heights, so did the skyscrapers.

Skyscrapers are an outcome of humanity's obsession with magnificent surroundings. An examination of the Wonders of the Ancient World, which include the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt and the Greek Colossus of Rhodes, reveals that from the very beginning of documented history, people have been interested in beautiful design. Skyscrapers are a significant part of this legacy and will continue to challenge the talents of engineers and architects into the future.

SKYSCRAPER OR HIGH RISE?

How do skyscrapers and high rises differ? While the terms are often used interchangeably, they are not exactly the same thing. Although the word skyscraper originated from mundane roots, modern usage has applied the term to a class of tall buildings. Skyscraper describes any very tall building that can be occupied. The term was first applied to buildings erected in the late nineteenth century. The height requirement for a classification as a skyscraper has changed over time. Today, anything taller than 800 feet (250 meters) is generally considered a skyscraper.

A high rise, on the other hand, is described by the Emporis Data Committee, which maintains building information for cities around the world, as any building taller than 115 feet (35 meters) that is divided into separate floors. By this definition, every skyscraper is a high rise, but the converse is not true. The term skyscraper has connotations of grandeur, as a soaring structure that seems to reach to the very heavens in a way that a mere high rise cannot hope to emulate.

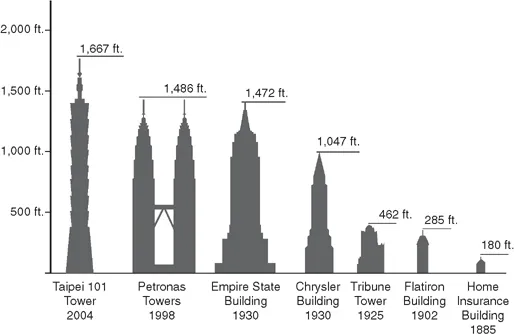

By comparing skyscraper heights, it is possible to see how far technology has improved the ability to create super-tall structures.

ORIGIN OF THE TERM

Skyscraper was originally a nautical term that referred to a moon sail, a triangular sail used on certain types of sailing ships, such as the elegant nineteenth-century clipper ships. The moon sail was the topmost sail and, as it seemed to scrape the sky, was called a skyscraper. There are also anecdotal references to the word skyscraper being used to describe exceptionally high-flying birds and particularly tall hats in the nineteenth century.

OVERCOMING OBSTACLES

Load-bearing masonry buildings reached new heights in the 1880s and 1890s, but it became clear that there were physical limitations to this type of construction that could not be overcome. If buildings were going to reach higher than a few stories, something stronger than bricks or masonry was needed to support them.

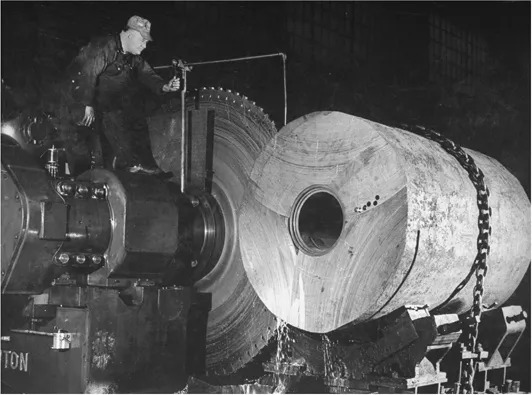

Enter flexible steel framing. The Bethlehem Steel Company, one of the largest suppliers to the U.S. shipbuilding industry, was one of several manufacturers that were developing new, innovative processes for manufacturing steel in the late 1800s.

The introduction of steel, which is stronger and lighter in weight than iron, made it possible for buildings to reach higher than ever before. Around the same time, reinforced concrete and the concept of the curtain wall were developed. A curtain wall is a building's outer covering that is supported by the steel frame structure; its purpose is to protect the building's interior from rain, wind, snow, and various other conditions. Unlike its load-bearing predecessors, a curtain wall only had to support its own weight. Heavy masonry siding could only be built to a certain height because the weight of these materials was such that, to build higher, the foundation walls below would have to have been extremely thick. Lighter curtain walls added less load to the structure, and, as a result, could be built higher than their stone counterparts. The first true curtain walls appeared in the early twentieth century. San Francisco architect Willis Polk designed the Hallidie Building, which used a system of exterior glass that was non-load-bearing. This spawned a wave of new development, but also revealed some immediate problems. In an era before air conditioning or insulated glass, Polk's buildings became a sort of sauna for their unfortunate occupants. Luckily, the necessary technology to make curtain walls really work was soon to come.

In the 1940s, the Bethlehem Steel Company was a busy place. Although some aspects of the process were automated, steel workers still played a very important role in the formulation and casting processes.

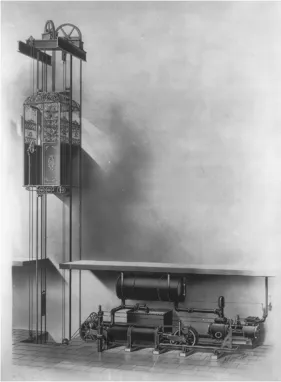

Materials were not the only obstacles to building taller buildings. Once all those floors were constructed, how were people going to get to them? As buildings grew to more than a few stories tall, staircases became impractical as a primary means of accessing the top floors. The invention of the safety elevator by Elisha Otis in 1854 opened up new possibilities for vertical travel. Building designs began to incorporate space for an elevator shaft, and advances in elevator design soon resulted in safer passenger transportation.

Why were taller buildings necessary? By the 1880s, space was becoming more and more precious in large cities, while at the same time more work and living space was required. Chicago's population growth was unprecedented, increasing from 112,000 in 1860 to nearly 300,000 in 1870.

Without elevators, the upper floors of skyscrapers would have been largely inaccessible.

Then tragedy struck. On October 8, 1871, the Great Chicago Fire left nearly one-third of the city homeless, destroying more than 18,000 buildings. Chicago began rebuilding almost immediately. The city bounced back not by simply replacing what was lost, but by outdoing the old Chicago. Given the opportunity to rebuild huge sections of the city, architects and designers embraced the newly available technology and built structures that reached for the sky. Never a city to be left behind, New York responded in kind, and the trend in these two metropolises was soon followed across the country.

THE LOGISTICS OF CONSTRUCTION

The construction of a skyscraper is a truly massive endeavor. After the land is secured, design established, and code clearances met, the site is excavated. To anchor a skyscraper firmly into the soil, a huge pi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Content

- About Frameworks

- Chapter 1 A Brief History Of Skyscrapers

- Chapter 2 Structural Steel

- Chapter 3 Elevators And Communications

- Chapter 4 Facades And Facing

- Chapter 5 Mechanical And Electrical Systems

- Chapter 6 Forces Of Nature

- Chapter 7 Skyscraper Demolitions And Disasters

- Glossary

- Find Out More

- Index