![]()

1 Economic and legal principles in renewable energy development policy

Many renewable energy enthusiasts have fantasized about a distant future day when our entire planet becomes fully energy-sustainable. In that utopian world, rooftops will be covered with photovoltaic (PV) solar shingles, wind turbines will grace the landscape like wildflowers, and all cars will run on batteries powered by the wind and sun. Coal smokestacks will no longer mar the skyline, and the air and water will be clean and clear.

In reality, the earth has a very long way to go before it approaches anything close to true energy sustainability and getting there will require countless trade-offs. Wind turbines can kill birds and alter pristine viewsheds. Solar panel installations can trigger neighbor disputes over shading and disrupt neighborhood aesthetics. And many sustainable energy strategies can complicate the management and funding of electric grids.

In other words, renewable energy projects do more than just generate clean, sustainable energy; they can also impose real costs on the communities that host them. Ineffective handling of these costs can spell the demise of a proposed renewable energy project, even if its aggregate benefits to society would easily outweigh its costs.

Savvy renewable energy developers are skilled at anticipating the costs that their projects might impose on third parties. They have strategies for mitigating these costs and for preventing them from unnecessarily thwarting a project’s success. The policymakers that most effectively serve their electorates’ interests in the context of renewable energy development are similarly adept at recognizing its potential costs and benefits and at structuring laws accordingly.

Humankind can only achieve a fully sustainable global energy system if the countless stakeholders involved in renewable energy development work together to resolve the myriad property conflicts associated with it. What principles should guide developers and policymakers in their ongoing efforts to prevent these inevitable conflicts from impeding the growth of efficient, equitable renewable energy development across the world? Serving as a foundation for the other chapters of this book, this chapter highlights some general concepts that can aid developers, policymakers, and other interested parties as they strive to manage the complex web of competing interests that often underlies modern renewable energy projects.

The microeconomics of renewable energy policy

Basic microeconomic theory can provide a useful framework for describing the incentives of the various players involved in renewable energy development. Simple economics can also bring the overarching objectives of renewable energy policies into focus in ways that are not possible through any other analytical tool. Because of economic theory’s unique capacity to elucidatethe complicated trade-offs at issue, anyone tasked with structuring laws to govern renewable energy should have a solid grounding in it.

Viewed through an economic lens, the optimal set of policies to govern renewable energy development is one that ensures that society extracts as much value as possible out of its scarce supply of resources. A given renewable energy project best promotes the social welfare—the overall well-being of all of society—only when it constitutes the highest valued use of the land and airspace involved. More broadly, social utility can be maximized only when humankind develops renewable energy projects solely on land and in airspace for which there is no other alternative use that is worth more to society.

Unfortunately, discerning whether a renewable energy project is the highest valued use of land and airspace at a given location is anything but easy. Just as no two parcels of land are identical, no two parcels are equally suitable for renewable energy. Although wind and sunlight can be harvested to some extent almost anywhere on earth, certain regions and places naturally have far more productive wind or solar resources than others. As illustrated by wind and solar resource maps available on the Internet,1 the potential energy productivity of wind and solar resources varies dramatically across the planet. Those variations can significantly impact whether renewable energy development is optimal in a given location.

In addition to variations in the quality of the wind or solar resources, countless other site-specific factors can affect the desirability of development at a given site. From a commercial wind energy developer’s perspective, the availability of road access, transmission capacity, and “off-takers” interested in purchasing a proposed project’s power at a favorable rate can greatly influence whether a site is well suited for development. In the context of rooftop solar development, an existing building’s orientation toward the sun and the slope and shape of its roof can impact whether installing a solar PV system on the building makes good economic sense.

Importantly, even many locations with exceptional wind or solar resources and favorable site-specific factors like those just described are nonetheless poor venues for renewable energy development. Specifically, projects in some of these locations may impose costs on neighbors and other stakeholders that are so great that they exceed the project’s benefits. These “external” costs—costs not borne by the primary participants in the development process—are largely the focus of this book.

Positive externality problems

When the parties directly involved in renewable energy development ignore the external costs and benefits associated with their projects, market failures that economists describe as “externality problems” often result.2 Basic economics principles teach that some sort of government intervention—a new legal rule or policy program—is sometimes the best way to mitigate externality problems and thereby promote greater economic efficiency.

In recent years, policymakers around the world have made great strides in crafting programs to address the positive externality problems plaguing the renewable energy sector. Positive externality problems exist in this context because wind and solar energy development generate significant benefits that are distributed diffusely among the planet’s billions of inhabitants, most of whom reside far away from the project site. Such benefits include reductions in the global consumption rate of fossil fuel energy sources and consequent reductions in harmful emissions, including carbon dioxide emissions that may contribute to global warming. Among countries that are net importers of fossil fuels, increasing the proportion of the national energy demand supplied through renewable resources can also promote economic growth, improve trade balances and advance greater economic stability.

Without some form of government intervention, rationally self-interested landowners and developers tend not to adequately account for external benefits in their decisions and thus engage in sub-optimally low levels of renewable energy development. Consider, for example, a rural landowner who leases thousands of acres of land to a developer for a commercial wind farm project.3 Such lease agreements typically give landowners an estimate of the monetary compensation they can expect to receive if the developer’s project is completed. Through power purchase agreements or other means, developers can also approximate how much financial compensation they will earn in connection with a given project. By weighing the expected benefits that would accrue directly to them against their own budgetary or other costs, landowners and developers can make rational, self-interested decisions about their involvement in the wind farm.

However, as mentioned above, renewable energy projects also generate numerous other benefits that accrue more generally to thousands or even billions of other people. In a completely free and open market, these ancillary benefits are not generally captured by project landowners or developers. Rational, self-interested landowners and developers are thus likely to place little or no value on these outside benefits and will instead weigh only their own potential benefits and costs when making development-related decisions. Because they rationally choose to ignore these external benefits, developers and landowners are likely to engage in sub-optimally low levels of renewable energy development without some form of government intervention.

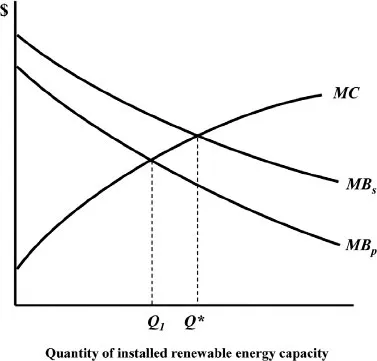

Figure 1.1 below depicts this concept graphically using simple marginal cost and marginal benefit curves. Suppose that, for a given wind or solar energy development project, a developer’s marginal cost of installing additional units of renewable energy generating capacity appears as curve MC. The tendency for developers to focus solely on their own marginal benefits from additional renewable energy installations (represented by the marginal cost curve MBp) rather than on the broader social benefits of such additional capacity (MBs) can lead them to install a quantity of installed capacity (Q1) that is less than the socially optimal amount (Q*). In summary, unless governments intervene to correct them, positive externality problems can result in an inefficiently low quantity of renewable energy development.

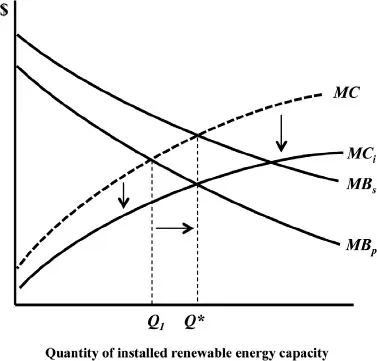

Governments across the world are well aware of this positive externality problem associated with renewable energy and have formulated a wide array of creative programs and policies aimed at countering it. Many of these programs seek to reduce the market cost of renewable energy development through direct subsidies, investment tax credits, special financing programs, streamlined permitting processes, and related means so as to effectively shift developers’ marginal cost curves downward.

This intended effect of incentive programs on the pace of renewable energy development is illustrated in Figure 1.2. Government subsidies, investment tax credits and similar cost-reduction programs seek to shift the marginal cost curve for renewable energy development downward from MC to MCi. All else equal, such cost reductions incentivize landowners and developers to increase the quantity of installed renewable energy generating capacity from Q1 to Q*.

Figure 1.1 Positive externality problems in renewable energy development

Figure 1.2 Intended effect of subsidies and related cost reduction programs on the quantity of renewable energy development

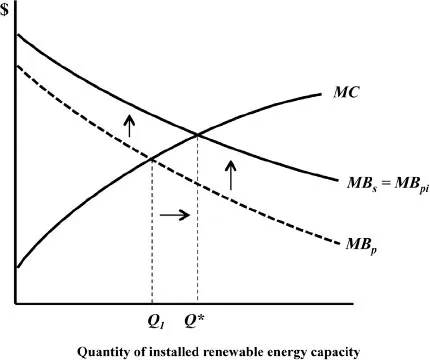

In contrast, renewable portfolio standards, feed-in tariffs and some other incentive programs seek to correct or mitigate the positive externality problems associated with renewable energy by helping developers to internalize more of the external benefits of their developments. These programs, which directly or indirectly increase the market price of renewable energy, effectively shift developers’ private marginal benefit curve (MBp) outward so that it matches or more closely approximates the social marginal benefit curve (MBs). Much of the recent growth in the global renewable energy sector can be attributed to these types of policies.

Renewable portfolio standard (RPS) programs enacted in much of the United States exemplify this policy strategy. These programs, which typically require utilities in affected jurisdictions to purchase some minimum amount of their energy from renewable sources, increase the market demand for and price of renewable energy.4 The United States’ per-kilowatt “production tax credit” for various types of renewable energy5 and various “feed-in tariff” programs common in some other countries6 are even more direct versions of this approach. Production tax credits and feed-in tariffs increase the marginal benefits of renewable energy development by artificially increasing the sale price of renewable energy itself.

As shown in Figure 1.3 below, to perfectly correct for positive externalities associated with renewable energy development, a policy strategy of relying solely on one of the aforementioned programs would need to be calibrated to shift developers’ private marginal benefit curve associated with development from MBp to MBpi such that it matched the social marginal benefit curve (MBs). If successful, such a program would thereby increase the quantity of installed renewable energy capacity to Q*, the optimal level.

Figure 1.3 Intended effect of RPS programs and feed-in-tariffs on the quantity of renewable energy development

Negative externality problems

Policymakers and academics devote comparatively less attention to many of the negative externality problems associated with renewable energy development. These problems arise when some of the costs associated with renewable energy projects are borne by individuals who do not directly participate in and have relatively less influence over development decisions.

The list of wind and solar energy development’s potential costs to outsiders is expansive and continues to grow. Within the land use realm alone, this list includes aesthetic degradation, noise, ice throws, flicker effects, interference with electromagnetic signals, destruction of wildlife habitats and wetlands, bird and bat casualties, disruption of sacred burial grounds or historical sites, inner ear or sleeping problems, annoyance during the construction phase, interference with oil or mineral extraction, solar panel glare effects, exploitation of scarce water supplies, and heightened electrical, lightning, and fire risks. Theoretically, an excessive quantity of renewable energy development can result when project developers base their renewable energy development decisions solely on their own anticipated costs and ignore costs borne by others.

It is true that most of the costs of renewable energy development are borne by developers and by the landowners on whose property the development occurs. Developers typically incur the greatest costs associated with any given renewable energy project. They frequently invest large sums of money in project planning, buying or leasing real property, paying for adequate road and transmission infrastructure,...