![]()

Chapter 1

Species Counterpoint in Major and Minor Modes

Species counterpoint has enjoyed a long and successful history as a teaching method, due to its approach of taking only a few steps at a time.1 The species method isolates difficulties from each other very usefully, so that the student does not have too much to contend with at any given moment. There is a risk, however, that exercises done via the species approach may seem more rigid and artificial than is musically desirable. For that reason, although we will begin our study within species counterpoint, we will soon endeavor to imitate the contrapuntal style of the great composers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries more directly. Only by constantly comparing our efforts with the work of these composers can we acquire the ability to imitate their style convincingly and to appreciate the vibrancy and integrity of contrapuntal textures at their finest.

1.1 Consonances: Note Against Note

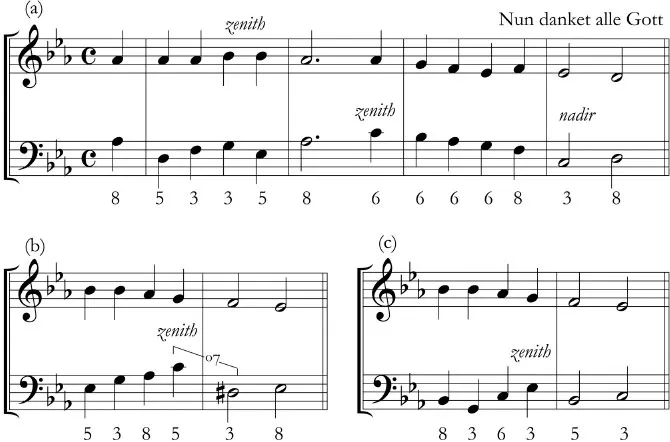

Example 1–1(a) presents the first phrase of the well-known Lutheran chorale Nun danket alle Gott (“Now thank we all our God”) in the major mode. It is rendered in two-voice counterpoint using only consonances: only major and minor thirds and sixths, perfect octaves, and perfect fifths (or their compound equivalents such as tenths, twelfths, etc.). One bass note is set against one melody note so that the rhythm of the bass line is identical to the rhythm of the melody. This type of homorhythmic counterpoint is called “note-against-note” or first species. Examples 1–1(b) and (c) are similar except that the chorale phrase, the opening of Jesu, meine Freude (“Jesus, my joy”), is in the minor mode. Play each of these through several times.

EXAMPLE 1–1

Since the study of counterpoint is essentially the study of writing melodic lines that can be satisfactorily sounded against other melodic lines, we must of course take melodic character into account, not just the harmonic intervals that result. Each line must become an entity in itself. One way of giving a line the quality of completeness or coherence is to provide it with a focal point toward which all the notes seem to move before reaching their final goal, the cadence. Often this focal point is the high point, the zenith, of the line; sometimes it is the nadir, the low point. Occasionally the zenith or nadir coincides with the final cadential note. There are other ways in which melodic focal points may come to our attention, but they generally involve more rhythmic variety than we are allowing ourselves at present. In the example above, the melodies are given: they are cantus firmi (“fixed songs,” abbreviated C.F., singular cantus firmus). In adding a counterpoint to a C.F., it is usually most effective to avoid placing the zenith of the new line at the same point as the zenith of the C.F. (To do so would detract from the mutual independence of the two lines.) Likewise, repeated notes in the C.F. should be offset by a change of note in the counterpoint. These guidelines reflect a certain basic principle of counterpoint: the opposition of linear musical ideas.

There are also important questions regarding the use of melodic intervals. Is stepwise motion always best? Is it okay to have two leaps in a row? If so, can they both be in the same direction? These and similar questions will continually come up throughout this study. It is probably best at the outset simply to try to get a feel for melodic lines by playing and singing the given examples several times. You may already be noticing certain intervallic tendencies, however, such as the change of direction of the line in both Examples 1–1(a) and (c) after two upward leaps in succession. Similarly, after a diminished melodic interval such as the diminished seventh (“°7”) in Example 1–1(b), the subsequent note usually moves by a half step in the opposite direction. This is heard as a kind of resolution of the diminished interval.

SELF-TEST 1–1

1. Choose the correct word or phrase:

(a) When two notes sound successively we speak of a harmonic / melodic interval.

(b) In first species counterpoint all / most / some of the harmonic intervals should be consonant.

(c) The following statement is true / false: augmented and diminished melodic intervals are forbidden in first species.

(d) The high point of a melodic line is called the zenith / nadir.

(e) The following statement is true / false: all perfect intervals may be used harmonically in first species.

2. Identify errors, if any, in the following first species counterpoint.

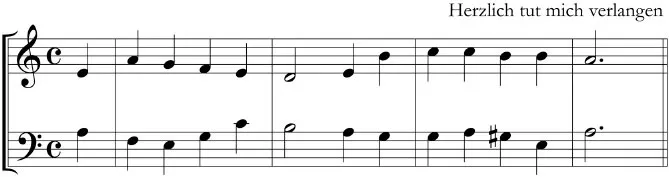

EXERCISE 1–1

Using Examples 1–1(a), (b), and (c) as models, add a bass line in first species to each chorale phrase given below.

1.2 Unstressed Dissonance: Two Against One

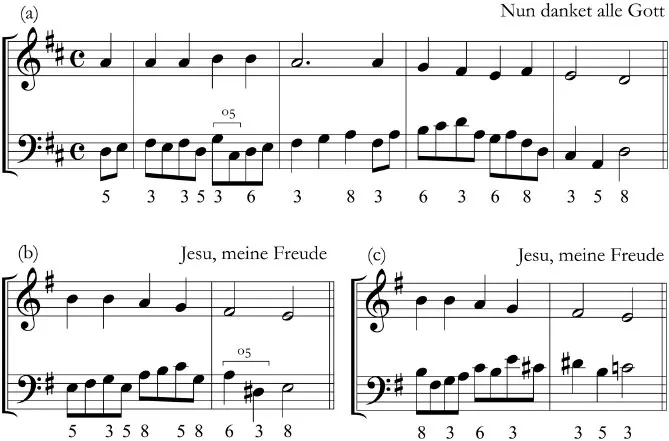

Study Examples 1–2(a), (b), and (c), which use the same chorale phrases as before, and play them through several times.

EXAMPLE 1–2

When a counterpoint introduces two notes against each note of the C.F., it is termed second species. A note on the second half of any beat (the “offbeat”) may feature a note that is a step removed from the consonant note occurring just before or just after. We call these notes of adjacency. As long as the note on the offbea...