Chapter 1

A Bioclimatic View of Architecture

1.1 Ventilation at the Eden Project.

‘Bioclimatic’ commonly describes architecture that utilizes and responds to local climate conditions. Bioclimatic design engages the building’s microclimate, form, and fabric in passive energy reduction strategies that reduce reliance on active mechanical systems.1 But there is more: Bioclimatic design is climate-responsive design that pointedly addresses the human element of design. It captures the wisdom of regional, vernacular, or biomimetic precedent while allowing a freedom of architectural expression suited for modern sensibilities and global technical aptitudes. This chapter introduces the tenets and origins of bioclimatic design by referring to the writing and research of influential contributors to this topic.

Climate and Nature

The Biomes at The Eden Project (Cornwall, UK, 2001) were conceived by Tim Smit and designed by Grimshaw Architects. Built in the scarred landscape of a spent clay pit in Cornwall, the project aims to build awareness of the interdependence of plants and people. The architectural aspect of the design conveys the ingenuity and efficiency of nature in bubble-shaped domes that settle into the irregular landscape of the pit. Hexagonal-shaped air-filled ETFE plastic panels in a steel geodesic frame cover Mediterranean and tropical biomes. An outdoor garden represents temperate climates. An education building, called the Core, was added in 2005. In addition to the efficient use of materials exhibited by the domes, the Eden Project generates and uses renewable energy, harvests rainwater and daylight, and recycles waste.2 A very special example of bioclimatic architecture, Eden is not only designed in response to its local climate but it also employs biomimicry, heals the landscape, educates about Earth’s ecosystems, and gives visitors a visceral experience in nature.

Climate and Culture

The culture of a place and its people is formed in part by the local climate, along with its animal and mineral resources and its geography. Climate informs social patterns of dress, habitation, gathering, and other customs. Bioclimatic architecture draws from the culture of a place and its people in the technical response to climate. For the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center in Noumea, New Caledonia (1992), Renzo Piano Building Workshop drew on the ‘climate intelligence’ of local materials and forms of vernacular buildings built by the island’s indigenous people, the Kanaks. The conical form of the traditional Kanak great house and the island’s forested terrain inspired a series of gracefully curved ‘cases’ that house the Cultural Center. Through a response to landscape, prevailing winds, and other factors of the tropical climate, the architecture taps deeply into the physiological aspect of the site. By providing spatial and material experiences that resonate with New Caledonian traditions, the architecture taps into the psychological and cultural aspect of the site. As Lisa Findley points out in an essay about the project, Piano’s design required a decidedly nonlocal technical solution. The soaring glue-laminated beams were fabricated overseas in France and other building components required technologically advanced fabrication not available locally.3 Bioclimatic design is not, in this example, synonymous with local or low-impact design. The expense and environmental impact of the imported and highly engineered construction materials can be seen to destabilize the balance of economics, environment, and equity in an idealized sustainability equation. Yet the project’s lasting contribution to New Caledonia’s architectural and cultural patrimony has its own measure. As with any architecture, the Eden and Tjibaou projects reveal the priorities and choices made in each building’s unique story of practice.

1.2The biomes at the Eden Project in Cornwall.

1.3Tjibaou Cultural Center, Noumea, New Caledonia.

1.4 Kanak house with carved roof finial.

In order to be considered bioclimatic, does architectural form need to be inspired by natural phenomena like the Eden Project or built on vernacular traditions as seen in the Tjibaou Cultural Center? These powerful methods produce some of the most memorable places but do not hold exclusive license in bioclimatic design. Some architecture finds inspiration in seeking a pure and optimal response to its physical environment and programmatic needs, finding beauty in the form that results from this optimization. Bioclimatic design can select among these different humanistic approaches, keeping in mind that a functional, technical design response to climate is fundamental and cannot be omitted from the approach.

1.5 A model of the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center.

Bioclimatic Design

Dictionary definitions of the word ‘bioclimatic’ emphasize the effects of climate on living organisms or the relations between these.4 The term was first used in biological research in the early twentieth century and later applied to the field of architecture. Embracing and inclusive of environmentalism and the passive solar and low-energy design movements that preceded it, bioclimatic design seeks to adroitly integrate passive and active strategies in an ecological humanistic response to climate. Bioclimatic principles form the basis of subsequent ecological and sustainable design philosophies that recognize the interdependence of design and nature.5 A first point of wide reference for bioclimatic architecture appears mid-20th century in the work of the Olgyay brothers.

DESIGN WITH CLIMATE

Hungarian-born émigré architects Victor and Aladar Olgyay developed their design methodologies while practicing and teaching architecture in the US, including many years at the Princeton School of Architecture in New Jersey.6 Victor Olgyay explains in the preface to Design with Climate: Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism (1963) why understanding the influence of climate on building is necessary: “With the widening spread of communications and populations, a new principle of architecture is called for, to blend past solutions of the problems of shelter with new technologies and insights into the effects of climate on human environment.”7

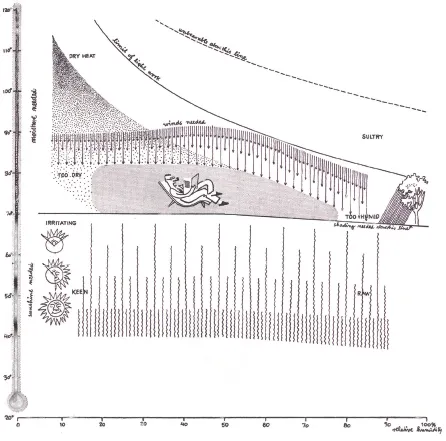

Though a half-century old, this injunction seems fresh, even more urgently appropriate. Olgyay continues on in the book’s preface to frame the problem of climate control as one requiring a multidisciplinary effort from the fields of biology (to understand human comfort), meteorology (to understand climate), and engineering (for the solution). The essence of Olgyay’s bioclimatic design approach is graphically represented in a “Schematic bioclimatic index” (Figure 1.6). Human physiological comfort is found to be a zone at the intersection of air temperature and relative humidity. In Olgyay’s method, climate data for a specific geographic location is plotted onto a bioclimatic chart that guides the designer to climate-specific passive design responses. Architectural strategies controlling sun, wind, and moisture are used to ameliorate the interior climate for the building occupant. Importantly, Olgyay urged architects to control the climate to meet human comfort needs by non-mechanical means whenever possible to ensure health, livability, and cost savings.

1.6Olgyay’s “Schematic bioclimatic index.”

A HOLISTIC VIEW

Olgyay’s philosophy of bioclimatic architecture, although objective in method, did not reject the subjective nature of design and human response to architecture; in fact, the premise of the work is based on a holistic view of humans in their environment. Notably, the figure at the center of the schematic bioclimatic index in Figure 1.6 is reclining in a zone of comfort. This illustrates human ability to adapt within a range of environmental factors and the limits to adaption, a topic alive today as the profession seeks strategies of adaptive comfort and studies occupant behavior.

Olgyay offers a worldview with humans at the center of cultural and physiological factors in the diagram “Factors influencing architectural expression” (Figure 1.7). In this view, architectural expression has moral, social, and historical dimension to its cultural aspect. Geological, climatic, and geographical dimensions make up the physiological aspect of architecture. These dimensions are manifest in our luminous, sonic, thermal, spatial, and animate built environment. As it responds to these influences, design necessarily passes through economic, physical, and emotional filters. Olgyay’s bioclimatic approach is intended to allow architects to synthesize and draw creative and informed results ...