eBook - ePub

Truth

About this book

In this critical introduction to contemporary philosophical issues in the theory of truth Pascal Engel provides clear and authoritative exposition of recent and current ideas while providing original perspectives that advances discussion of the key issues. This book begins with a presentation of the classical conceptions of truth - the correspondence theory, the coherence theory and verificationist and pragmatist accounts - before examining so-called minimalist and deflationist conceptions that deny truth can be anything more than a thin concept holding no metaphysical weight. The debates between those who favour substantive conceptions of the classical kind and those who advocate minimalist and deflationist conceptions are explored. Engel argues that, although the minimalist conception of truth is basically right, it does not follow that truth can be eliminated from our philosophical thinking as some upholders of radical deflationist views have claimed. Questions about truth and realism are examined and the author shows how the realism/anti-realism debate remains a genuine, meaningful issue for a theory of truth and has not been undermined by deflationist views. Even if a metaphysical substantive theory of truth has little chance to succeed, Engel concludes, truth can keep a central role within our thinking, as a norm or guiding value of our rational inquiries and practices, in the philosophy of knowledge and in ethics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Classical theories of truth

1.1 A preliminary map

Before examining various classical philosophical conceptions of truth, let us try to characterize the main features of our naïve, commonsensical conception of it. We have a predicate, “true”, in all languages1 (wahr, vrai, verum, alèthès, pravdy, etc.), which we apply to all sorts of items — thoughts, beliefs, judgements, assertions, ideas, conceptions, views, theories, and so on — which seem to refer to the contents of our thoughts, which are abstract, or a least non-concrete, entities. We apply, however, this predicate also to concrete things, such as pictures, artefacts, pieces of currency, or even living animals. For instance we say that this is a true drawing by Poussin, that this is a true copy of a document, a true 50 euro banknote, a true piece of artillery or a true Irish setter. In such cases, the meaning of “true” seems to be the same as “authentic”, “real”, “faithful”, “exact”, or “conforming to” a model or a type. Sometimes too we employ “true” to characterize other sorts of properties, such as character traits, when for instance we talk of a true friend, meaning that the person is loyal or trustworthy.

All these meanings, however, seem to derive from two basic ones: “true” as a property of an item that makes it genuine, natural or real, as opposed to contrived, artificial or fictional; and “true” as a relation between some item to which the predicate is attributed, and some other item which makes true the first item. The former is what one calls, in the current philosophical vocabulary, the truth-bearer, and the latter what one calls the truth-maker. As we have just remarked, the truth-bearers are usually considered to be the content of information transmitted by various concrete entities, mental (“ideas”) or physical (sentences, drawings on a piece of paper, patterns of symbols, sounds emitted), rather than the concrete entities themselves. It is uncontroversial that we often apply the predicate “true” to concrete physical items, such as sentences (sequences of sounds or symbols), but it seems clear that we attribute it to the content of the sentences, rather than to the physical entities of which they are made up. We say “This sentence is true”, but we do not say “This sequence of sounds is true”. Similarly when we say such things as “I wish my dreams came true”, we refer to the content of our dreams, not to the psychological or physical events that appear in our brains. Finally, our ordinary notion of truth is such that when we say that a certain utterance or belief is true, we intend to say that it has a certain further characteristic than the mere fact that we have the belief or that the utterance has been performed. We use it to refer to an objective property that our beliefs, statements, and such like have, independently of us. In other words, the fact that we call something true or false seems to mark a real distinction between the things that have these properties and the things that don’t. And we take it that this distinction is due to a property of our thoughts that they have in virtue of their relation to the real world.

This last feature also stands in contrast with another: our ordinary use of the word “true” is such that it simply marks the fact that we have endorsed an assertion or a statement. When someone says: “The volcano has erupted”, and when someone else wants to agree, that person says: “It is true”, meaning that he or she endorses the previous assertion. The two statements “The volcano has erupted” and “It is true that the volcano has erupted” do not exactly mean the same thing, for the latter contains the mark of approval, but in so far as what is said is concerned, they have the same cognitive content. In this sense the words “is true” do not designate a further characteristic from the fact that the sentence has this content: the predicate “is true” does not seem to be on a par with such properties as “is square” or “weighs 3 kilos”. When we say that a thought is true, we do not seem to be attributing to it a genuine property. This potentially conflicts with the previous intuition that truth is an objective property of our thoughts.

So far this is not very philosophically controversial, although there is room to elaborate philosophical ideas from these simple observations. Philosophy starts when one remarks that it is not obvious that these features of our predicate “true” are features of a single, unified concept, and that it is not easy to define it. First, it is not evident what the bearers of truth are. A long philosophical tradition, going back to the Stoics and represented in contemporary philosophy by Frege and Carnap among others, claims that the truth-bearers are propositions, abstract entities expressed by linguistic sentences. Another tradition, going back to Descartes and classical empiricism, claims that the truth-bearers are ideas, beliefs, or mental representations (or sometimes “judgements”, conceived as made up of ideas) that also carry a certain content, but that tends to be mental or psychological in nature. And some philosophers, from Ockham and Hobbes to Quine, have claimed that the bearers of truth are sentences or physical symbols, or at least entities locatable in space and time, like utterances.

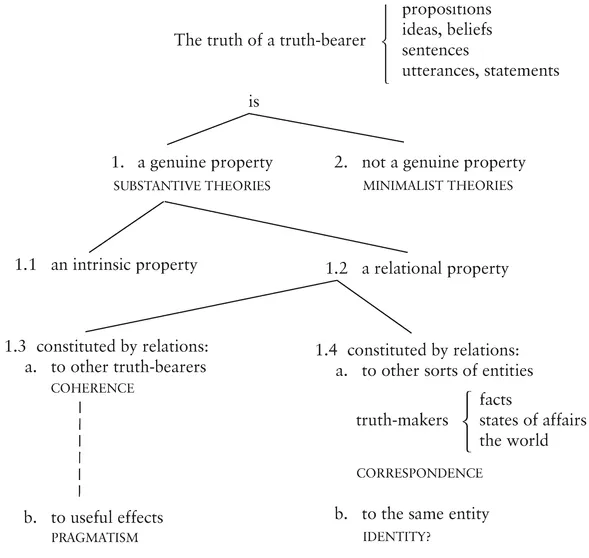

Secondly, there is disagreement about what kind of property truth is. Let us leave aside for the moment the view that truth might not be a genuine property, and let us assume that it is a real characteristic. Some philosophers hold that truth is an intrinsic or monadic property of truth-bearers, one that they have absolutely and in virtue of nothing else, and not in relation to other things (for instance, being happy is a monadic property, whereas being a brother is a relational one). But the most common view is that truth is a relational property, that holds between truth-bearers and other entities. The most classical conception is that truth is a relation of correspondence, of adequacy or of fit, or perhaps identity, between the true items and something else, the truth-makers. Among such conceptions, there is disagreement about the nature of these truth-makers: some philosophers claim that they are entities of a different kind from truth-bearers — facts, states of affairs, or situations in the world; others do not make such fine distinctions and are happy to say that truth is correspondence with reality. Another relational conception is that truth is a relation between the truth-bearers themselves, that is, between propositions and other propositions, beliefs and other beliefs, sentences and other sentences, when they make some coherent whole. Such conceptions are called coherence conceptions of truth: according to such views, there is no need to appeal to truth-makers as some further entities and to a relation distinct from the one that holds between the truth-bearers. Or rather truth is not a property of truth-bearers, but of sets or wholes made up of them. Another view, pragmatism, is that truth relates to the useful effects of our conceptions. Prima facie, these conceptions are not equivalent or compatible: they involve quite distinct ontological commitments. At this point it seems that the philosophy of truth is part of metaphysics, and here as elsewhere there can be more or less economical, or more or less profligate, ontologies. Armed with such ontologies, the task is to account for the fact that truth is objective, and marks a genuine difference between truths and non-truths. To a large extent, this is what “theories of truth” are about. We can try to draw a preliminary map: see Figure 1.2

Figure 1

As we shall see, this figure does not exhaust the possible options. For instance option 2, that truth is not a genuine property, characterizes what we shall call minimalist theories, in contrast with substantive ones. The full meaning of this contrast will only be appraised in Chapter 2. It is also important, when we say that the options indicated here characterize various “theories of truth”, to be clear about what such a phrase means. It often refers to different kinds of questions, which can be easily conflated. One can ask: (a) “What is the meaning of our ordinary word ‘true’”? and in general the answer will involve an account of the various central uses of this word in our language; (b) “What is our concept of truth?”, and the answer will involve an account of the role played by this concept within our overall conceptual scheme, in relation to other concepts; (c) “What are the criteria of truth?”, and the answer will involve an account of the means by which we recognize that something is true; (d) what truth is, and the answer will provide a definition of truth. Finally (e) there is also a sense of “theory of truth” and of “definition of truth” that occurs in the context of axiomatic theories of truth for a language, but we shall leave it aside for the moment and examine it in §2.3.

For the moment, let us restrict ourselves to questions (a)—(d). These correspond to separate enquiries, although they are obviously connected. One can give an account of the meaning of “true” without intending to say anything about what truth is, or by what epistemological criteria we identify it. And one can give these criteria without defining it. For instance, we can say that certainty is a criterion of truth without prejudging what truth is.3 Similarly, it is one thing to elucidate what concept of truth we have, and another thing to say what truth is (compare: our concept of water is the concept of a translucent liquid, but water is H2O). But it seems difficult to say that our concept of truth has no relationship with what we mean by the word “true”, nor with our criteria for truth. And in a sense, a definition of truth should tell us what this notion really means. Perhaps a more neutral term, such as “conception” or “account”, would be more appropriate, but presumably a complete theory of truth, in the philosophical sense of this term, should try to answer all these questions, and to trace their connections. In general the classical theories of truth that we shall examine here all attempt to give definitions of truth, in the sense of explaining what the real nature or essence of this property is, even when they are prepared to recognize that truth might not be a property or a “thing” in the ordinary sense. The notion of definition, like that of analysis, admits a looser and a stricter sense: on the one hand an analysis or definition is an account of a concept and an elucidation of its connections with other concepts; on the other hand, it is a real definition, attempting to reduce an entity to other, simpler, ones, in the sense of a reduction. This means that we hope to provide something like necessary and sufficient conditions for a definition of truth in terms of another, more primitive, property. Now the notion of necessary and sufficient conditions is usually expressed by the logical connective “if and only if” (where the if conjunct is the sufficient condition, and the only if conjunct is the necessary condition”; abbreviated to “iff”). Hence our definitions can be framed under the following form of an equivalence (which we shall meet quite often):

(Def T) X is true iff . . .

where “X” stands for some appropriate truth-bearer, and the blank on the right-hand side stands for some appropriate definiens or necessary and sufficient condition for X. The various “theories” of truth will aim first at filling this blank. Now if this necessary and sufficient condition stands for some real, explanatory property or set of properties, the theories in question will be called substantive or robust ones. Whether such theories make sense or not is one of the main questions that we have to address. The option that truth cannot be defined, and that the blank cannot be filled by a substantive explanation, does not figure explicitly in Figure 1, but it is an open one. As we shall see, it makes its appearance at every turn.

1.2 Correspondence

The most common definition of truth present in the philosophical tradition is the most intuitive one: truth is a relation of correspondence between the contents of our thoughts and reality, or between our judgements and facts:

(Correspondence) X is true iff X corresponds to the facts

A correspondence conception of truth is often called a realist conception in the following sense: it says that our thoughts are true in virtue of something that is distinct from them, and independent from our thinking and knowing of them. In this sense, the truth of a statement is also supposed to transcend our possible knowledge of it, or its verification. In opposition, we may call anti-realist any conception of truth according to which truth does not transcend our cognitive powers, and is constrained by some epistemic condition. The use of the word “realism” at this stage of our enquiry is bound to be vague, for it will turn out that we shall be able to characterize a view as realist only when we are able to see whether, and if so in what sense, it involves a distinctive conception of truth. In this sense, any enquiry into the nature of truth will have to construct the various senses of “realism” at issue, and must not take it as given. Moreover, as we shall see, correspondence is not the only possible realist conception of truth. But we can, for the moment, use the general characterization just given. Correspondence theories are supposed to spell this out in virtue of a relation which is, to use the traditional scholastic phrase, a relation of “adequacy” of things to the intellect (adaequatio rei et intellectus).

It is often said that the first explicit formulation of this definition occurs in a famous passage in Aristotle’s Metaphysics that I have already quoted: “To say of what is that it is not, and of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, or of what is not that it is not, is true” (Metaphysics Γ, 7, 1011b, 26). But this passage is far from clear. To take up our distinctions of the previous section, it is not obvious that Aristotle is here giving a definition of truth, rather than a characterization of the meaning of “true”. In some passages, he e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Truth lost?

- 1 Classical theories of truth

- 2 Deflationism

- 3 Minimal realism

- 4 The realist/anti-realist controversies

- 5 The norm of truth

- Conclusion: Truth regained

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Truth by Pascal Engel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.