eBook - ePub

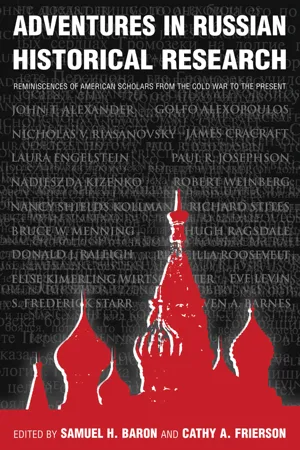

Adventures in Russian Historical Research

Reminiscences of American Scholars from the Cold War to the Present

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Adventures in Russian Historical Research

Reminiscences of American Scholars from the Cold War to the Present

About this book

American historians of Russia have always been an intrepid lot. Their research trips were spent not in Cambridge or Paris, Rome or Berlin, but in Soviet dormitories with official monitors. They were seeking access to a historical record that was purposefully shrouded in secrecy, boxed up and locked away in closed archives. Their efforts, indeed their curiosity itself, sometimes raised suspicion at home as well as in a Soviet Union that did not want to be known even while it felt misunderstood. This lively volume brings together the reflections of twenty leading specialists on Russian history representing four generations. They relate their experiences as historians and researchers in Russia from the first academic exchanges in the 1950s through the Cold War years, detente, glasnost, and the first post-Soviet decade. Their often moving, acutely observed stories of Russian academic life record dramatic change both in the historical profession and in the society that they have devoted their careers to understanding.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adventures in Russian Historical Research by Samuel H. Baron,Cathy Frierson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Educational Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

My Historical Research in the Soviet Union

Half-Empty or Half-Full?

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “adventure” as follows:

1 a: an undertaking usually involving danger and unknown risks; b: the encountering of risks (the spirit of adventure); 2: an exciting or remarkable experience (an adventure in exotic dining); 3: an enterprise involving financial risk.

For several generations we students of Russia and the Soviet Union have had peculiar and confining experiences. Our colleagues in European history as a matter of course did extensive research, occasionally for years at a time, in the countries of their choosing, and easily studied and even obtained advanced degrees there. We were generally banned from the archives and frequently from the country of our specialty, except for painfully established and extremely limited scholarly exchanges and conferences. Whereas no one counted the foreign men and women who studied or engaged in research in Paris, London, or Rome, we were glad to obtain our dozen or two dozen slots and had to hope that nothing untoward would happen during a given year to spoil our chances for the next. When one of the Soviet exchange students went into a drunken stupor and was failed at Columbia University, one of our students was promptly sent home from Moscow. One of my Ph.D. candidates, a Canadian from a Russian family, was accused, resoundingly, of wrecking, but fortunately was allowed to leave the Soviet Union promptly though with his research materials (he was writing a dissertation on the Slavophiles) lost. Throughout, Russian and especially Soviet studies remained at a high level of political tension and vituperation, comparable to such subjects as the Holocaust and the Vietnam War. On the one hand, during the Cold War politics helped to provide our field with U.S. government and foundation subsidies, nostalgically remembered at present. On the other hand, that circumstance added to the partisan and combative nature of our area of interest and its relative isolation from other areas. A few of our very best scholars, such as professors Father Georges Florovsky and Gleb Struve, refused on principle to set foot in the Soviet Union or to have anything to do with it.1

Perhaps even more significant in their negativity toward Soviet learning have been the reactions of many scholars outside our field when for the first time they encountered Marxist-Leninist or Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist historiography. My Berkeley colleague Henry May, a splendid American intellectual historian, went unprepared to a joint American-Soviet conference dealing with the eighteenth-century Enlightenment in the two countries. He was horrified by the encounter. What shook him most in the Soviet papers and discussion was the crudeness and the simplicity of the approach to the subject, and especially the totally irrelevant quotes from the classics of Marxism as well as from Lenin and Stalin. Poor Henry, so upset that everything had to be treated in a crass Marxist manner in the Soviet intellectual world, did not know that many subjects could not be treated there at all.

Still, without challenging the moral stance of Georges Florovsky and Gleb Struve or dismissing the just criticisms of Henry May, I must admit that I have been an enthusiastic supporter of the regular cultural exchange between the two countries from its inception in the late 1950s to the present. It has proved to be of enormous help to us and to our students, many of them now professors contributing to this volume. Russian history is based overwhelmingly on Russian sources, Russian publications, and Russian historiography, just as France is indispensable for French history and Germany for German history. In addition to what Russia could contribute to almost every scholarly project in our field, the very perception of the general context is of great significance. In isolation, too many of our graduate students have come to think of topics in Russian history in terms of two or three books available in English. And exchange, together with the general easing of travel and communication, has already improved knowledge of the Russian language on the part of most of our researchers beyond the point that Professor Maurice Friedberg, a wit in our midst, designates “intermediate Russian.”

Even Soviet historical scholarship itself is a rich and many-faceted subject with strong as well as weak characteristics. In discussing it, I often used the image of a glass half-empty or half-full. I remember, for example, talking with a former student of ours, now a fine professor, a man of the left, by the way, not of the right—historical opinion was never divided simply into left and right. His topic was the Revolution of 1905 and its interpretation by scholars, including Soviet historians. My companion said: “Oh, I dismiss Soviet writings.” “All right,” I said, “if you dismiss Soviet writings”—I had just finished reading his manuscript on 1905—“why then do you mention historian A so often?” He replied: “Well, historian A is an exception. He is fine.” I asked: “How about Historian B?” He replied: “You must know what I think of historian B, but he is the only person to use these documents.” “And historian C?” “Historian C is in a class by himself, he is so good. Don’t even mention him with the others.” Well, it was not necessary to continue. One usually finds historians A, B, and C, as well as others, as one studies one’s Russian topic.

Good history could be and was written in the Soviet Union. Several considerations help to explain this rather rare happy outcome. To begin with, the Soviet system as we knew it became fully formed only with the Stalinization of the country in the early 1930s. The preceding period may be called transitional, but it was strongly linked to the past. Also, even after it had been fully formed, the Stalinist system had its more permissive as well as its restrictive phases. Different aspects of history were treated differently. Thus, it was much easier to do serious work in economic than in religious history. Besides, the audience mattered. Especially in the Brezhnev era, highly specialized and advanced studies usually suffered little from censorship, while historical works for mass readership had to deal in black and white, present their heroes as paragons of every virtue, and so on. Most importantly, as I shall explain later in more detail, the imposed fundamental historical framework usually allowed genuine historical investigation in at least some directions that would not endanger that framework.

All of these circumstances and still others permitted the writing of some good history in the Soviet Union, and all of it was in the open, so to speak, above board. But Soviet writers, historians included, also specialized in beating the system—in a sense, it even became a great game. Perhaps the most common way to do this was to include programmatic Marxist statements in the introduction and the conclusion and to ignore them in the body of the text. I did not know whether to laugh or cry when one of the best, perhaps the best, Russian historian of the nineteenth century told me, “Nikolai Valentinovich, note that I mention that view in the introduction and the conclusion, but not a word of it in the text.” Other messages, intended or not, can also be obtained from Soviet books. One of my favorite such studies—people in our field often have favorites—is a volume on the revolutionary movement in Russia in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. The point is that there was no such movement. In fact, this book is a fine example of negative evidence. The author, a fully qualified scholar, had gone through the archives as I had not. Thanks to him, I know that there was nothing on the subject to find. His laudatory tone merely emphasizes the lack of serious evidence.

One of the joys of visits to the Soviet Union turned out to be its people. I must say that almost all of my Soviet colleagues, professors, librarians, archivists, and researchers of various kinds did all they could, within the allowable limits, to help me and my work. Surprisingly, in addition to books and other materials I had asked for, still other items were often brought, which apparently someone deemed useful for my research. And the selection of these extra items was usually very good. My papers and research presentations were well attended and well received. Some of them led to long and interesting discussions. The advantages ranged from occasionally getting a thorough and able critique of what I was doing from a different perspective, to obtaining a wealth of factual and bibliographical information I would not have obtained otherwise. Although at times hesitant, most Soviet academics seemed glad to talk to me. Especially in the earlier years of the exchange, the presence of a foreign scholar appeared to be an event. I remember having dinner in the apartment of Professor Petr Andreevich Zaionchkovskii when he answered a telephone call informing him that he was permitted to invite me.

Moreover, I found the same friendly and admiring attitude toward foreigners, in particular Americans, outside academic circles. I remember a chauffeur for the Academy of Sciences telling me that he knew there was no race problem in the United States. When, somewhat taken aback, I asked him how he knew this, he answered that it was because the Soviet media kept insisting there was one. Many such examples could be cited, but I remember a certain episode above all others. In the course of several sabbatical years, my wife Arlene and our children would remain in Paris while I worked several weeks or even several months in the Soviet Union. Arlene would come to Moscow or to Leningrad for a week or ten days of wonderful sightseeing and general celebration sponsored by our Soviet hosts. This time it was Leningrad, and we were trying to have dinner in a good restaurant on Nevsky Prospect. We managed to get in with the help of a strange character who claimed that he was soon to emigrate to the United States. At a recent medical convention he had asked two American doctors unknown to him to sign papers certifying that he was their nephew, and they had done so. We sat at a long table with perhaps ten or twelve naval officers. I spoke Russian with them, English with Arlene. Suddenly, one officer asked: “What is your wife speaking, Finnish?” “No, English.” “Why English, who is she?” “An American.” “What a fine fellow!” he exclaimed. “Married an American.” I shall never forget his look of approval and fascination.

The positive Russian attitude toward foreigners was all the more remarkable because, in a sense, we had everything and they had almost nothing. Once, I found something to buy in a berezka store (these shops were established to attract hard currencies), namely, a wooden toy of a peasant and a bear jointly chopping a log, like the one my father had when growing up in Kostroma. But the Academy car was waiting impatiently. I explained the situation to the vendor in Russian, of course, and promised to pick up the toy and pay for it in the afternoon. She responded: “This is not for such as you, this is only for foreigners.”2

It was the people in the Soviet Union who were kind, not the system. I have already referred to the “allowable limits,” and they were tight. Only after the collapse of the Soviet Union did the wife of a Soviet colleague, and by then a friend of mine, tell me that when Arlene came to Moscow, she had petitioned the Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences to be allowed to invite us for dinner. She received the reply: “They are already being given one dinner. Enough.” More seriously, when Arlene suddenly had to have major surgery in Paris, the bureaucrats arranged for my report to be given immediately rather than several weeks later as scheduled. But instead of expediting my flight to Paris, they had me fill out paper after paper affirming that my early departure was voluntary and I had no claims against the Soviet Union; and they encouraged me by saying that, according to their government’s information, surgeons in Paris were excellent and I had nothing to worry about. One bureaucrat added: “If she dies, she dies; if she lives, she lives.” She lived.

Scholars had many opportunities and advantages when part of an exchange. Most of our participants were preoccupied with their own research, although that usually included at least some consultation with Soviet colleagues, occasional presentations of the results of their research, and other means of participation in Soviet intellectual life. For example, I was invited to attend Professor Militsa Vasilevna Nechkina’s seminar, as well as some meetings at the Institute examining the research projects of its members.

As a theme for one of my research trips to the Soviet Union, I sought a better acquaintance with Russian and Soviet historiography, one of my lifetime interests. I asked in particular for interviews with a number of leading Soviet historians. I had selected major figures whom I had never met, or had met only very briefly, rather than Boris Aleksandrovich Rybakov, who had been my brother Alexander’s mentor during the first graduate student exchange between the two countries and with whom I had maintained relations ever since, or a friend such as Petr Andreevich Zaionchkovskii. Although all of those to be interviewed were prominent scholars who had presented their historical views richly in books and had no reason to impart revelations to me, my expected gain was obvious: the details should fit into the pictures I already had of them, and the men themselves would become closer and somehow more human. And, indeed, I learned something about Soviet historiography and perhaps even about historiography in general, although not always as I had planned.

The first meeting, with Academician Lev Viktorovich Cherepnin, was in certain ways a disaster. I began awkwardly by noting that my host was both a continuer of the mainline Russian historical tradition and a leader of Soviet scholarship, and asked him to comment on the relationship between the two. He answered: “Nikolai Valentinovich, one must know how to renounce the old world and live one’s way [vzhitsia] into the new.” And so it went. Only at one point, when he realized that my father had been a student of Vasilii Osipovich Kliuchevskii, probably the most famous historian of Russia of all time, he became somehow less formal and more accessible. But that didn’t last long. And Cherepnin concluded loudly in praise of Marxism and Soviet historiography. Whatever my interest in the interview, he clearly used it only to reaffirm his Marxist credentials. And what could I expect from someone with Cherepnin’s painful past—he had been arrested and exiled, and was now addressing for the first time a foreigner he did not know? (Despite the earlier unpleasantness, he along with Rybakov and a very few others had risen to the highest levels of the Soviet historical guild.)

The problems with Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Zimin were quite different. He surprised and almost disconcerted me by having read some of my books in preparation for the interview, and by offering respectful and helpful advice. I, in turn, wanted to discuss his important work on the sixteenth century, but we never got to that. Once my topics were out of the way, Zimin could talk only about The Lay of the Host of Igor. I knew, to be sure, that the situation was a very tense one. A few days earlier, I had been advised by a Soviet colleague not even to mention Zimin’s name when I came to visit Rybakov. Zimin had denied the authenticity of The Lay of the Host of Igor, the pearl of ancient Russian literature. Rybakov was one of its most ferocious defenders. But, although I could not plead ignorance, I kept missing something. Thus, when Zimin said that he had been accused of a lack of patriotism, and even of treason, I commented that we were, after all, historians and had to go with the evidence. He replied: “You do not understand me. I am more patriotic than all of them.” Zimin went on and on, and the climax came when he charged me with a mission. I, an American, a Russian, and a Russian scholar, must tell the world about the behavior of another American, Russian, and Russian scholar, Roman Osipovich Jakobson, in the crisis over The Lay. I am now discharging my mission. Jakobson, a leading proponent of the authenticity of The Lay, came to a conference on the subject in Moscow. He telephoned Zimin and, according to Zimin, the conversation went as follows: “Jakobson speaking, give me quickly your manuscript—there is not much time left before the conference.” “Roman Osipovich, we have not even been introduced to one other.” “You are not giving it! Alright. I shall tear it apart [raznesu] just the same.” I obtained from my interview with Zimin the most complete list as of that time of his published writings related to The Lay of the Host of Igor. In his case, as in a number of others, the Soviet authorities did not simply ban his publishing on the subject, but limited it in effect to short pieces in out-of-the-way periodicals.

I shall not proceed interview after interview, but I should mention one more, the most memorable, although it was not part of the series I have been dealing with, and not even in Russian history. At that time, I was writing my book on Charles Fourier3 and was briefly in Moscow for another reason, but I decided to seek out the best Soviet specialist on Fourier, Ioganson Isaakovich Zilberfarb. I found him easily at an historical institute of the Academy, and he received permission to have lunch with me. We went through the line in a nearby cafeteria and sat down at a table for two. Zilberfarb then got up from the table and brought me a big apple. The rapport was immediate because Zilberfarb was a kindly, well-mannered, and soft-spoken Russian intellectual like many of the people with whom I had been brought up. I concentrated on the bibliography of our subject, which he had probably mastered better than anyone else in the world.4 I hurried because I did not know how long we could be together. Still, when the apple was gone, I found time to ask Zilberfarb about his letter to a prominent periodical. That periodical had published a scholarly article about Fourier’s anti-Semitism. Fourier had, in fact, been anti-Semitic along the lines common in his time, namely, in believing that the Jews were always middlemen and did not themselves produce anything of v...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- About the Editors and Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. My Historical Research in the Soviet Union: Half-Empty or Half-Full?

- 2. A Tale of Two Inquiries

- 3. Discovering Rural Russia: A Forty-Year Odyssey

- 4. Catherine the Great and the Rats

- 5. Exploration and Adventure in the Two Capitals

- 6. Leningrad, 1966–1967: Irrelevant Insights in an Era of Relevance

- 7. Adventures and Misadventures: Russian Foreign Policy in European and Russian Archives

- 8. Reclaiming Peter the Great

- 9. Prisoner of the Zeitgeist

- 10. Of Outcomes Happy and Unhappy

- 11. A Journey from St. Petersburg to Saratov

- 12. Romancing the Sources

- 13. Russian History from Coast to Coast

- 14. Friends and Colleagues

- 15. Within and Beyond the Pale: Research in Odessa and Birobidzhan

- 16. Mysteries in the Realms of History and Memory

- 17. A Historian of Science Works from the Bottom Up

- 18. Orthodoxies and Revisions

- 19. Post-Soviet Improvisations: Life and Work in Rural Siberia

- 20. Hits and Misses in the Archives of Kazakhstan

- Index