![]()

PART I

Introduction

![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Wolfgang F. E. Preiser , Aaron T. Davis , Ashraf M. Salama, and Andrea Hardy

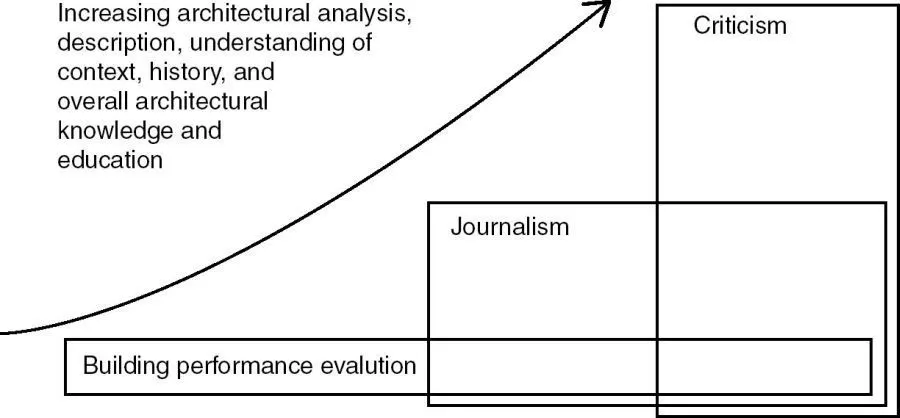

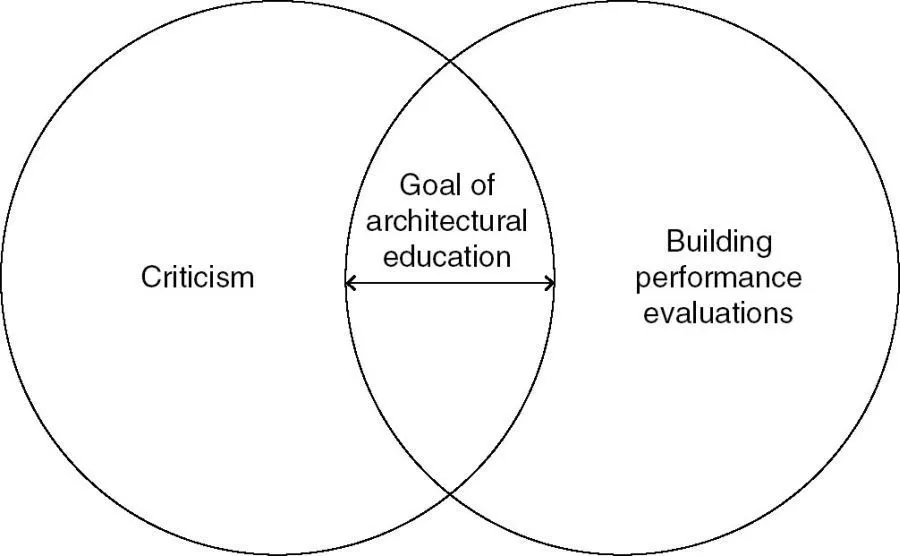

Synopsis

This book aims to establish a dialogue between perceived and measured quality in architecture in two ways: first by recognizing and illuminating commonalities between the two; second by finding areas within the ontological frameworks of each capable of supporting the differences. The “habitability framework” presented later in this chapter is one such structure to be expounded upon that shows how aesthetic and the performative aspects can in some cases even complement each other. With few exceptions, architectural criticism has been carried out by and large by “expert critics” employing subjective methods of assessment focused primarily on the aesthetic properties of buildings; rightly so, the understanding of buildings as composed formal objects traces back to the beginnings of the profession. In contrast, traditional environmental design evaluation uses objective criteria and methods of measuring the performance of buildings, using metrics focused on health, safety, security, functionality, psychological, social, and cultural satisfaction of the building occupants. The development of criticism in architecture over time admittedly did not keep pace with the technological improvements and innovations radically changing the way buildings were being conceived of and built. In other words, as the facility to understand buildings from the design-side evolved, criticism based in the same scientific inquiry did not also evolve as a clear discipline with its own boundaries. Whether this is because critics identify primarily as journalists and are not typically building professionals is up for discussion, especially since there is an increasing need for the combination of evaluation, journalism, and criticism, as shown in Figure 1.1. Nevertheless, the technological developments in the production of buildings, the rise of “big data,” optimization, focus groups, and the use of commissioning and building performance evaluations (BPE) are increasingly included as part of the project delivery method and life-cycle analysis. These requirements of building performance, and the time lag between their regulation and integration, only exacerbate the schism between professional practice, discourse, and pedagogy. Architectural practice has the responsibility to engage criticism more directly and intelligently than with the mere supply of marketing images. The academy is tasked with providing a creative environment in which creativity can flourish within the bounds of technical reality. The discourse and criticism must mediate between the two by providing an educational platform of technical innovation vis-à-vis the history of the built environment, but also present the aspirational qualities that make architecture unique to a given time and place, as shown in Figure 1.2. In a market saturated with unreal images and the tin-ringing of sycophantic praise, nothing less is demanded than a built environment rooted in the manifold definitions of quality, or permanence, of accountability in the face of slick rhetoric; an Architecture Beyond Criticism.

FIGURE 1.1 Increasing architectural analysis, description, understanding of context, history, and overall architectural knowledge and education

Source: Andrea Hardy.

FIGURE 1.2 The need for the academy to enlarge the overlap of criticism and performance evaluations in architectural education

Source: Andrea Hardy.

Juxtaposing criticism and performance evaluation

Criticism is defined as the “the art of judging the qualities and values of an aesthetic object” (Sharp 1989). In his classical writing Art as Experience (1934), John Dewey states that criticism is judgment as an “act of intelligence performed upon the matter of direct perception in the interest of a more adequate perception” (Dewey 1934). This underscores the subjective nature of criticism as the dialogue between a perceiver and a thing-perceived. Sharp argues for this personal interpretation and notes that most criticism is written for popular or specialist consumption (Sharp 1989). However, he attempts to elevate the status of criticism by introducing objectivity as the ultimate goal, and responsibility, of the critic. In Sharp’s words, “the importance of objectivity has to be stressed. A lot is demanded of the critic in the judicious administration of this goal. It has to be allied to good sense and clear judgment, to sagacity and it must be in the hands of someone who can hold their own against the spread of mediocre mass cultural values” (Sharp, 1984). The objectivity of the “clear judgment and sagacity” of an individual is debatable; if no criteria are available for comparison, it seems that merely the attempt would suffice. How would these criteria be established, however, if not by consensus, in part, from the “mediocre mass cultural values” (i.e. the audience criticism is supposed to be insulated from but also consumed by)? Furthermore, true objectivity of criticism in the traditional architectural model would be to presume that Architecture with a capital “A” has been unadulterated by the race to broad-based mediocrity in popular culture; a claim that, surveying the pseudo-diversity amalgam of style and rhetoric available today, is comically untenable.

Unlike contemporary criticism in architecture, which tends toward style, a significant segment of building performance evaluations (Preiser and Schramm 1997; Preiser and Vischer 2005; Mallory-Hill, Preiser, and Watson, 2012) has evolved after the fact, from Post-Occupancy Evaluations, or POE studies. These are regarded as a branch of environment-behavior studies and they are conducted on a building or a portion of a built environment for different purposes. In some cases, they are performed to solve problems that might occur in buildings after they are occupied. In other cases, results are used to improve specific spaces within a built environment through continued users’ feedback, including that of sustainability of the building, and “the need of thorough analysis of the building sector in order to understand its situation in relationship to the social demand for sustainability” (Casals et al. 2009). Other reasons for conducting performance evaluation include documenting successes and failures of performance in order to justify requests for renovations, additions, or new construction.

An important feature in the majority of performance evaluation studies (both measured and perceived) is that it involves systematic investigation of opinions, perceptions, and viewpoints about built environments in use, and from the perspective of those who use them. However, in all cases, POEs respond to the habitability of a building, “designing while acknowledging and understanding human needs and thus designing for more meaningful and richer life experiences” (Rowley-Balas 2006). The habitability of a programmed, designed, and evaluated building can lead to the question, “Are designers and architects really asking the right questions?” (Rowley-Balas 2006). This question and the subject of habitability is one of the main links between building aesthetics and building analysis. Who is it designed for, how does it perform as an integrated system, and then how is it used?

The answers to the above questions lie in an integrative conceptual framework presented in the following section on “Elements of the habitability framework.” The term “habitability” means that the designed and built environment is intended for human habitation, with different levels of priority and performance regarding human needs. For example, King Hammurabi reminded builders that if people were harmed by buildings, those who were responsible for their construction were to be put to death (Preiser 2003). Vitruvius coined the famous words “firmness, commodity and delight,” which equate to three expected and basic levels of performance in buildings (Mallory-Hill, Preiser, and Watson 2012). When seen from this perspective, aesthetic performance falls within the category of “delight,” namely the psychological, social, and cultural appropriateness and satisfaction of the building occupants. In other words, architectural criticism in this integrated worldview is subsumed in the domain of “delight” with its three constituent parts and categories. How is the integrated framework used? It applies to the entire building delivery and life-cycle, as outlined in the “Building Performance Process Model” (Preiser and Vischer 2005).

Elements of the habitability framework

Starting in the 1960s, habitability research referred to the US Navy, NASA, and US Army Corps of Engineers’ efforts (Shibley 1974; Meere and Grieco 1997; Kitmacher 2002; Riola and de Arboleya 2006; Howe and Sherwood 2009; Harrison 2010) to improve the quality of environments and respective person–environment relationships, for example in shipboard habitability research. A working definition for the term “habitability” is offered by the editors: “Habitability refers to those qualitative and quantitative aspects of the built environment which support human activities in terms of individual and communal goals.” A chronology of habitability is presented in Table 1.1.

The term “habitability” is derived from the original meaning of the word “habitat,” i.e. the species’ natural home that is comfortable and fit...